August 20th, 2017  U.S. District Judge Steven “Not So” Merryday denied an Assistant U.S. Attorney’s (AUSA) motion to delay a trial because a witness employed by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) had prepaid for a trip to view the August 21, 2017 solar eclipse in totality. U.S. District Judge Steven “Not So” Merryday denied an Assistant U.S. Attorney’s (AUSA) motion to delay a trial because a witness employed by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) had prepaid for a trip to view the August 21, 2017 solar eclipse in totality.

The court reasoned that the delay would “subordinate the time and resources of the court … to one person’s aspiration to view a ‘total’ solar eclipse for no more than two minutes and forty-two seconds.”

Can’t take issue with the result, but instead of just saying that, the magistrate–perhaps seeking his own two minutes and forty-two seconds of fame–penned a silly too-cute-for-words order built around Carly Simon’s 1972 hit “You’re So Vain.” Can’t take issue with the result, but instead of just saying that, the magistrate–perhaps seeking his own two minutes and forty-two seconds of fame–penned a silly too-cute-for-words order built around Carly Simon’s 1972 hit “You’re So Vain.”

You may recall that Simon’s anonymous, self-absorbed antagonist (suspected to be Warren Beatty) “flew [his] Learjet up to Nova Scotia to see the total eclipse of the sun.” (Speculation has it that Carly was referring to the 1970 total eclipse that was viewable along the East Coast of the United States).

In his order denying the motion to postpone, Judge Merryday mocked the AUSA who filed the motion for “boldly mov[ing] … where no AUSA has moved before” and for “oddly” describing the eclipse “‘scheduled to occur,’ as if someone arbitrarily set the eclipse, as an impresario sets a performer to appear at a chosen time and place.”

He unnecessarily ridiculed the witness for his prepaid “personal indulgence,” again invoking the Carly Simon song, which featured this line immediately preceding “the total eclipse of the sun” line: “Well I hear you went to Saratoga, and your horse naturally won.”

When an indispensable participant, knowing that a trial is imminent, pre-pays for some personal indulgence, that participant, in effect, lays in a bet. This time, unlike Carly Simon’s former suitor, whose “horse, naturally won,” this bettor’s horse has–naturally–lost.

Meanwhile, he diminished the significance of a total solar eclipse as “just another astral event.” The rare August 21 total eclipse will be the first to travel from coast to coast within the United States in nearly 100 years.

–Order, United States v. Joseph Bishop, U.S. District Court, Middle District of Florida, Tampa Div., Case No. 8:17-cr-266-T-23JSS (Aug. 18, 2017) (Thanks to David Barman.)

May 18th, 2015  Stock photo – Not the real guy. Leave it to insurance coverage guru/legal humorist Randy Maniloff to track down the most interesting cases for his monthly publication, Coverage Opinions. Among this month’s excellent articles (which include a mock interview with Tom Brady), Randy revisits his insurance Coverage for Dummies contest with the case of Blank-Greer v. Tannerite Sports, LLC, No. 13-1266 (N.D. Ohio Apr. 21, 2015).

Here are the basic facts, borrowed from Randy’s excerpts from the court’s opinion:

In May 2012, [James] Yaney’s friend, Jason Vantilburg, in anticipation of the birth of his first child, asked Yaney to host a party to celebrate. Yaney and Vantilburg fashioned the party into a ‘diaper shootout,’ where guests could bring diapers for the new baby and enjoy an afternoon shooting guns in Yaney’s backyard. As a ‘grand finale’ to the party, they also decided to blow up an old refrigerator.

In preparation, Yaney used his [Yaney] Motorsports truck to haul the refrigerator from Vantilburg’s home to his property. He then used his trailer to tow a box van to his backyard so that guests had a target to shoot. On the day of the event, Yaney set up the Motorsports truck and trailer as a staging area for guns and ammunition. ***

Towards the end of the event, Yaney and Vantilburg decided it was time to blow up the refrigerator. They hauled the refrigerator from Yaney’s pole barn into the backyard. Guests stood behind tables fifty meters away from where the refrigerator was located. Vantilburg moved into position behind his rifle, fired at the explosives [H2] inside the refrigerator, and detonated them. The refrigerator immediately blew apart and sent shrapnel flying across the yard. A piece of shrapnel hit (guest) Plank–Greer’s hand, nearly severing it.

Read Randy’s full account of the case, which addressed the issue of whether the party host was acting in the scope of employment with respect to insurance coverage from his business. The court said no.

–Blank-Greer v. Tannerite Sports, LLC, No. 13-1266 (N.D. Ohio Apr. 21, 2015)

January 9th, 2015  Don’t think for a minute that Canadian judges can’t keep up with American judges when it comes to Strange Judicial Opinions. Wild and crazy judicial happenings in Canada are here, here and here. Don’t think for a minute that Canadian judges can’t keep up with American judges when it comes to Strange Judicial Opinions. Wild and crazy judicial happenings in Canada are here, here and here.

Now comes a new hit TV series, I mean, an order in a divorce case, entered by Superior Court Justice Pazaratz, where the court analogized the parties’ ugly divorce to the hit television show, Breaking Bad. Excerpts from the order include:

1. Breaking Bad, meet Breaking Bad Parents.

2. The former is an acclaimed fictional TV show whose title needed a bit of explaining: “BREAKING BAD: A southern U.S. expression for when a good person suddenly loses their moral compass and starts doing bad things”.

3. The latter is a sad reality show playing out in family courts across the country. “BREAKING BAD PARENTS: When smart, loving, caring, sensible mothers and fathers suddenly lose their parental judgment and embark on relentless, nasty litigation; oblivious to the impact on their children”.

4. SPOILER ALERT: The main characters in both of these tragedies end up pretty much the same: Miserable. Financially ruined. And worst of all, hurting the children they claimed they were protecting.

5. To prolong the tortured metaphor only slightly, the “urgent” motion before me might be regarded as this family’s pilot episode. Will these parents sign up for the permanent cast of Breaking Bad Parents? Will they become regulars in our family court building, recognizable by face and disposition? Or will they come to their senses; salvage their lives, dignity (and finances); and give their children the truly priceless gifts of maturity and permission to love.

6. Stay tuned.

[The court proceeds to recount the parties’ inability to work together, accusations and counter-accusations, and their deadlock in trying to reach a custody sharing arrangement. The Court decides on a reasonable arrangement before wrapping things up.]

36. One final comment:

37. I hope I didn’t offend the parties with my Breaking Bad Parents analogy. They’re not bad parents. Yet.

38. Mainly, I was trying to give both parties a sobering warning: Stop!

39. Stop being nasty.

40. Stop jockeying for position.

41. Stop playing hardball.

42. Stop acting like you hate your ex more than you love your children.

All good advice, Justice Pazaratz, but you’ve just ruined the potential for the TV series.

–Coe v. Tope, Case No. 2839/14, Ontario Superior Court of Justice (July 3, 2014). Thanks to whoever sent this along. We lost track of the original email. Let us hear from you!

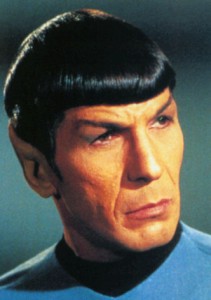

August 14th, 2013  A litigation strategy the judge thought went too boldly beyond … In an order littered with Star Trek references, a litigation strategy involving obtaining the copyright to pornographic movies and then suing people for illegally downloading them irked U.S. District Judge Otis D. Wright (C.D. Cal.) to the extent that he levied hefty sanctions against those involved in various misdeeds.

According to Judge Wright, the plaintiffs had outmaneuvered the legal system:

They’ve discovered the nexus of antiquated copyright laws, paralyzing social stigma, and unaffordable defense costs. And they exploit this anomaly by accusing individuals of illegally downloading a single pornographic video. Then they offer to settle—for a sum calculated to be just below the cost of a bare-bones defense. For these individuals, resistance is futile; most reluctantly pay rather than have their names associated with illegally downloading porn. So now, copyright laws originally designed to compensate starving artists allow, starving attorneys in this electronic-media era to plunder the citizenry.

The following findings of fact flesh out the situation a bit more:

2. AF Holdings and Ingenuity 13 have no assets other than several copyrights to pornographic movies. There are no official owners or officers for these two offshore entities, but the Principals are the de facto owners and officers.

3. The Principals started their copyright-enforcement crusade in about 2010, through Prenda Law, which was also owned and controlled by the Principals. Their litigation strategy consisted of monitoring BitTorrent download activity of their copyrighted pornographic movies, recording IP addresses of the computers downloading the movies, filing suit in federal court to subpoena Internet Service Providers (“ISPs”) for the identity of the subscribers to these IP addresses, and sending cease-and-desist letters to the subscribers, offering to settle each copyright infringement claim for about $4,000.

4. This nationwide strategy was highly successful because of statutory copyright damages, the pornographic subject matter, and the high cost of litigation. Most defendants settled with the Principals, resulting in proceeds of millions of dollars due to the numerosity of defendants.

An apparent Star Trek fan, Judge Wright began his order imposing sanctions by quoting Spock from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan: “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.”

Not sure of the exact relevance of this quotation. Was he referring to the needs of the many for illegally downloaded porn?

He continued mining the Star Trek vein at various parts of the order, stating, for example, that “though Plaintiffs boldly probe the outskirts of law, the only enterprise they resemble is RICO. The federal agency eleven decks up is familiar with their prime directive and will gladly refit them for their next voyage” and “[i]t was when the Court realized Plaintiffs engaged their cloak of shell companies and fraud that the Court went to battlestations.”

Order Issuing Sanctions, Ingenuity 13 LLC v. John Doe, Case No. 2:12-cv-8333-ODW(JCx), May 6, 2013, U.S. District Ct., Central District of California. Thanks to Michael Kong.

May 26th, 2013  Federal judge a fan of this venerable exotic dancer. Chief U.S. District Court Judge Fred Biery, W.D. Tex, had a great time writing a preliminary injunction order in a case in which the City of San Antonio passed an ordinance regulating topless dancers, including requiring them to wear more clothes. How much fun did he have? The title of the order gives a good clue:

“The Case of the Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Bikini Top v. The (More) Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Pastie,” with a footnote to—you guessed it—the novelty hit, Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini (Knapp Records 1960). The order is a combination of lame sexually oriented wordplay and thoughtful analysis. Here are two sample paragraphs of the former (underline added):

An ordinance dealing with semi-nude dancers has once again fallen on the Court’s lap. The City of San Antonio (“City”) wants exotic dancers employed by Plaintiffs to wear larger pieces of fabric to cover more of the female breast. Thus, the age old question before the Court, now with constitutional implications, is: Does size matter?

The Court infers Plaintiffs fear enforcement of the ordinance would strip them of their Profits, adversely impacting their bottom line. Conversely, the City asserts these businesses contribute to reduced property values, violent crime, increased drug sales, prostitution and other sex crimes, and therefore need to be girdled more tightly. Plaintiffs, and by extension their customers, seek an erection of a constitutional wall separating themselves from the regulatory power of City government.

The order then veers into hyper-weirdland, explaining that while no amicus curiae briefs had been filed, the court had the benefit of input from volunteer “curious amigos” who performed on-site inspections. Judge Biery advises the volunteers “they would have enjoyed far more the sight of Miss Wiggles, truly an exotic artist of physical self expression even into her eighties, when she performed fully clothed in the 1960s at San Antonio’s Eastwood Country Club.” He even includes a picture of Miss Wiggles. Er, thanks for that, Judge.

Things settle down at that point with an analysis of the request for preliminary injunction by the plaintiff club owners, pitting the government’s interests in reducing crime and protecting property values against the First Amendment. Under the law, the club owners can get a license and let their dancers wear pasties or operate without a license and make them wear bikini tops.

Judge Biery wasn’t convinced female breasts were the cause of the government’s asserted ills, saying he “doubts several square inches of fabric will stanch the flow of violence and other secondary effects emanating from these businesses” and speculating that “[a]lcohol, drugs, testosterone, guns and knives are more likely the causative agents.”

But he denied the preliminary injunction because the law does not require the government to prove causation in this instance, ending with more provocative wordplay (“Should the parties choose to string this case out to trial on the merits, the court encourages reasonable discovery intercourse as they navigate the peaks and valleys of litigation, perhaps to reach a happy ending.”)

(Postscript: A student sent me this, but many other sources have publicized this order, including Above the Law and the ABA Journal.)

—35 Bar and Grille v San Antonio, 35 Bar & Grille, LLC, et al. v. City of San Antonio, Civil Action No. SA-13-CA34-FB (W.D. Tex., Apr. 29, 2013) (Biery, J.)

October 26th, 2012  In this Halloween-themed case, the plaintiff bought a house, only to learn that it had a reputation in the Village of Nyack, NY, for being possessed by poltergeists, a reputation built in large part on the seller’s previous efforts to promote the house as haunted, which were unknown to plaintiff. On learning of the alleged haunting, plaintiff sued for rescission of the sale contract. In this Halloween-themed case, the plaintiff bought a house, only to learn that it had a reputation in the Village of Nyack, NY, for being possessed by poltergeists, a reputation built in large part on the seller’s previous efforts to promote the house as haunted, which were unknown to plaintiff. On learning of the alleged haunting, plaintiff sued for rescission of the sale contract.

The New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division, over one dissent, ruled for the plaintiff, going against the usual rule in New York of strict caveat emptor (let the buyer beware), which imposed no duty on house sellers to disclose even known defects. Based on the seller’s previous assertions that the house was haunted, the court said the seller was estopped from claiming otherwise and that the house was haunted “as a matter of law.”

So New York property owners take note: there is no duty to report collapsing roofs, faulty foundations, or termite infestations, but, after this opinion, suspected poltergeist infestations must be disclosed. (The case was decided in 1991; New York may have modified its caveat emptor rule since then.)

We’ll let the court–per Judge Rubin–unravel this hair-raiser. Turn the lights low, cuddle up, and prepare for the one and only judicial ghost story, a classic tale of a stranger arriving in a town where things aren’t quite what they seem. [Cue spooky music]:

The unusual facts of this case … clearly warrant a grant of equitable relief to the buyer who, as a resident of New York City, cannot be expected to have any familiarity with the folklore of the Village of Nyack. Not being a “local,” plaintiff could not readily learn that the home he had contracted to purchase is haunted.

Whether the source of the spectral apparitions seen by defendant seller are parapsychic or psychogenic, having reported their presence in both a national publication (“Readers’ Digest”) and the local press …, defendant is estopped to deny their existence and, as a matter of law, the house is haunted.

More to the point, however, no divination is required to conclude that it is defendant’s promotional efforts in publicizing her close encounters with these spirits which fostered the home’s reputation in the community. In 1989, the house was included in a five-home walking tour of Nyack and described in a November 27th newspaper article as “a riverfront Victorian (with ghost).” The impact of the reputation thus created goes to the very essence of the bargain between the parties, greatly impairing both the value of the property and its potential for resale. ….

While I agree… that the real estate broker, as agent for the seller, is under no duty to disclose to a potential buyer the phantasmal reputation of the premises and that, in his pursuit of a legal remedy for fraudulent misrepresentation against the seller, plaintiff hasn’t a ghost of a chance, I am nevertheless moved by the spirit of equity to allow the buyer to seek rescission of the contract of sale and recovery of his down payment.

New York law fails to recognize any remedy for damages incurred as a result of the seller’s mere silence, applying instead the strict rule of caveat emptor. Therefore, the theoretical basis for granting relief, even under the extraordinary facts of this case, is elusive if not ephemeral.

“Pity me not but lend thy serious hearing to what I shall unfold” (William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act I, Scene V [Ghost] ).

From the perspective of a person in the position of plaintiff herein, a very practical problem arises with respect to the discovery of a paranormal phenomenon: “Who you gonna’ call?” as the title song to the movie “Ghostbusters” asks. Applying the strict rule of caveat emptor to a contract involving a house possessed by poltergeists conjures up visions of a psychic or medium routinely accompanying the structural engineer and Terminix man on an inspection of every home subject to a contract of sale.

It portends that the prudent attorney will establish an escrow account lest the subject of the transaction come back to haunt him and his client–or pray that his malpractice insurance coverage extends to supernatural disasters.

In the interest of avoiding such untenable consequences, the notion that a haunting is a condition which can and should be ascertained upon reasonable inspection of the premises is a hobgoblin which should be exorcised from the body of legal precedent and laid quietly to rest.

The court detailed New York’s strict caveat emptor rule, but ultimately couldn’t stomach the fact that it was the defendant who, in effect, created the defect by broadcasting the house’s haunted status, thereby impairing its value:

In the case at bar, defendant seller deliberately fostered the public belief that her home was possessed. … Where, as here, the seller not only takes unfair advantage of the buyer’s ignorance but has created and perpetuated a condition about which he is unlikely to even inquire, enforcement of the contract (in whole or in part) is offensive to the court’s sense of equity. Application of the remedy of rescission, within the bounds of the narrow exception to the doctrine of caveat emptor set forth herein, is entirely appropriate to relieve the unwitting purchaser from the consequences of a most unnatural bargain.

The dissenting judge wanted to stick with the caveat emptor rule, stating that “if the doctrine of caveat emptor is to be discarded, it should be for a reason more substantive than a poltergeist.”

–Stambovsky v. Ackley,169 A.D.2d 254 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1991)

October 4th, 2012  Good news for legally inclined zombie lovers. Joshua Warren has compiled a casebook on Zombie Law that “include[s] case opinions from the over 300 U.S. Federal Court opinions with the word “zombie” (and “zombies”, “zombi”, “zombis”, “zombified”, “zombism”, etc..).” These include cases from the zombified Supreme Court (available as postcards, along with zombie law teeshirts and zombie flashdrives). Good news for legally inclined zombie lovers. Joshua Warren has compiled a casebook on Zombie Law that “include[s] case opinions from the over 300 U.S. Federal Court opinions with the word “zombie” (and “zombies”, “zombi”, “zombis”, “zombified”, “zombism”, etc..).” These include cases from the zombified Supreme Court (available as postcards, along with zombie law teeshirts and zombie flashdrives).

Warren explains that this is a “serious” project. From his promotional website:

The “zombie” in federal courts are very interesting. Aside from the intellectual property cases that provide some reflection on modern zombie fiction, there are also ample metaphoric uses of the word in these judicial writings. Judges have referred to “zombie precedents” and “zombie litigation”. There are zombie corporations, zombie criminals, a significant number are social security cases in which people describe themselves in zombie condition and even a recent mentions of cybernetic zombies.

Unlike other works of zombie academia, the zombies in this book are all real. Most zombie scholarship uses hypothetical zombies as tropes to create entertaining and extreme fact patterns that can be used to explain complex subject matters. This has been used effectively for neuroscience (Schlozman, Voytek), international policy analysis (Drezner), public health (Center for Disease Control), geography (Kickstarter project: Zombie-Based Learning), survival skills (Brooks) amongst other subjects (See Zombie Research Society) including also academics who focus on the fictional character itself (Mogk, Brooks).

This Zombie Law book is different because it does not use zombies as hypotheticals to teach law. It is not conjecture about what zombies are or might be. This book is a compendium of real usages of the actual word in American jurisprudence. This book is a collection of real legal cases that literally include “zombies” (or similar word) in US Federal Court opinions..

The basic outline of the book will separate most cases into issues of corporations, medications, criminals and, of course intellectual property. Major sections will be devoted to Social Security (disability) law, corporate fraud and issues of criminal intent. There are noteworthy cases referring to post traumatic stress disorder and many recent Social Security cases regarding of fibromyalgia. The intellectual property cases are about popular zombie fiction and also so-called “vicious zombi” patents. In general, the idea of zombies in a mall is public domain for copyright but particular forms of zombie products are protected by trademark.

Frequently there is a sort of double meaning in the word. In Social Security cases, the word zombie is found as a symptom of pain, depression and anxiety but also the side effect of medications prescribed for those same symptoms. In criminal law, zombie appear in victim’s description of their assailant’s behavior but also as defense argument against criminal intent. For corporations the ironic question of corporate-personhood begs the question, ‘what is a person?’, which is often the implied question of zombie studies.

For all you law professors and other legal authors who thought there was no niche left to write about, Warren shows you just have to think outside of the box, in this case, the ones buried six feet under.

September 24th, 2012  Betting the professor was this federal judge’s favorite Gilligan’s Island character. In an opinion that is part period-piece shipwreck thriller and part Gilligan’s Island pop-culture fun, Chief U.S. District Judge William Steele (S.D. Ala.) attempted to unravel a dispute over the ownership rights to an unidentified shipwreck off the coast of Alabama. The wreck is believed to be either the Clipper Ship ROBERT H. DIXEY or the British barque AMSTEL.

Several parties, including the United States and Alabama, claimed title to the wreck. Unfortunately, whichever ship it was, it sank more than 150 years ago, leaving Judge Steele to observe in a footnote that historical scholars were better-suited than a federal judge to determine the ship’s identity:

FN4. This procedural posture is highly unusual. For starters, the proper identity of Shipwreck # 1 is a matter better suited for spirited scholarly discourse than black-letter judicial construction. Yet the parties have submitted their dispute to a federal judge, not a 19th century maritime historian. Furthermore, while both sides agree that 100% certainty as to the vessel’s identity is not possible, resolution of this factual issue does not turn on the sort of credibility determinations for which an evidentiary hearing would be appropriate. The underlying events having taken place a century and a half ago, there are no live witnesses to recount the circumstances under which the DIXEY and the AMSTEL sank. Nor are there dueling expert witnesses whose theories might be poked and prodded via cross-examination. Instead, as the DIXEY Claimants succinctly state, “[t]here is what there is.”

But Judge Steele did a pretty good scholarly job himself in recounting the interesting history of both ships, starting with the DIXEY, where he invoked the 1960s sitcom, Gilligan’s Island, for a unifying thread (Gilligan’s Island references have been bolded):

Just sit right back and you’ll hear a tale, a tale of a fateful trip. It did not start in a tropic port, nor aboard a tiny ship. On August 15, 1860, the Clipper Ship ROBERT H. DIXEY set sail that day from New York to Mobile, carrying a cargo described only as “miscellaneous hardware.” The DIXEY reached an anchorage in Mobile Bay on the evening of September 14, 1860. By inopportune coincidence, the DIXEY arrived at the Bay just hours ahead of a Category 1 hurricane. Wary of the approaching storm, Captain Dixey (by all accounts a skipper brave and sure) put out “double anchors and all chain” at 10 p.m., and took “all measures to ride out a storm.”

The hurricane struck at approximately 2:00 a.m. on September 15, 1860. The DIXEY actually weathered the first few hours of the storm well. With the winds out of the south, the DIXEY was sheltered by the buffering presence of Dauphin Island (to the vessel’s south) from the worst of the rough seas, at least initially. After 8:00 a.m., however, the eye of the hurricane passed, and fierce winds shifted to the north. The weather started getting rough, and the mighty ship was tossed. In its anchored position, the DIXEY was exposed to approximately 17 miles of open shallow water stretching all the way to Mobile. As a result, the DIXEY was pounded by the punishing winds and roiling seas. The first anchor’s chain broke at around 10:00 a.m. The DIXEY’s crew began working feverishly to cut away its masts and sails, thereby lightening the ship and reducing its wind exposure, even as the DIXEY took on water for over an hour. If not for the courage of the fearless crew, the DIXEY would have been lost. Alas, the gale continued to worsen and the other anchor chain snapped, causing the DIXEY to be buffeted by the hurricane, tossed around in the shallow water like a child’s toy. The wind and seas pushed the helpless DIXEY south down the shipping channel of Mobile Bay for some 12 miles. [The DIXIE ultimately was pounded to pieces by the storm.]

Judge Steele also recounted the AMSTEL’s fate, another interesting story, but left out any pop culture references. Aw, come on, Judge. As Sammy Hagar sang with Van Halen, you gotta finish what you started. Maybe he ran dry on Gilligan’s Island’s references, but he always could have switched to a Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald theme.

In the end, the judge ruled that the ship was the AMSTEL, but ordered the parties to continue gathering evidence and let him know if he got it wrong.

From the scholarly bent of this opinion–setting aside the Gilligan’s Island references–I’m guessing “The Professor” was Judge Steele’s favorite Gilligan’s Island character.

Fathom Exploration, L.L.C. v. The Unidentified Shipwrecked Vessel or Vessels, etc., in rem, Civil Action No. 04-0685-S-M. (S.D. Ala., Mar. 12, 2012).

September 17th, 2012  In this class action against T-Mobile for allegedly reactivating stolen phones after they were reported stolen, the plaintiffs invoked a recipe metaphor from another case, but the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit turned it around on them. The court opined the closest the plaintiffs came to explaining the trial court’s alleged error In this class action against T-Mobile for allegedly reactivating stolen phones after they were reported stolen, the plaintiffs invoked a recipe metaphor from another case, but the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit turned it around on them. The court opined the closest the plaintiffs came to explaining the trial court’s alleged error

is when they quote (in their reply brief) a metaphor from an opinion in another case: “Just as one bad ingredient can spoil a stew, one error of law can spoil an order.” Gray v. Bostic, 625 F.3d 692, 697 (11th Cir. 2010) … [Explaining Gray as a case where the error was blended in the trial court’s decision and distinguishing it from the instant case where the trial court, in the court’s opinion, stated independent valid grounds for its ruling against plaintiffs.] That was why the error spoiled the stew in Gray. Here, the district court’s decision was not contained in a single pot with blended ingredients but instead was contained in a number of pots containing different ingredients. If a bad ingredient went into some of the pots, that would not spoil what was dished out of a pot that was free of the ingredient.

The Eleventh Circuit upheld the district court’s denial of class certification. Meanwhile, I have a bone to pick with, er, or stir into, the merits of this suit. The federal district court denied class certification on the basis that the value of stolen phones can’t be uniformly determined. Accordingly, common questions of fact did not predominate, as required for the plaintiffs to obtain class certification under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Here is the district court’s take on the absolutely insurmountable problem of valuing stolen phones:

Here, Plaintiffs contend that “in this era of Ebay and other public online sites selling used phones by the millions, determining a particular model phone’s value is a relatively simple matter of online research.” However, they certainly offer no concrete proposal or methodology about how to effectively and accurately manage such online research on a nationwide basis. For example, when conducting online research, would 2011 be the year to use for establishing the value for a used phone of a certain model or would the year in which the phone was misplaced or stolen be the more appropriate time frame? Plaintiffs also ignore how individualized issues relating to the age of the phone, what contents or applications were previously on the phone, and whether the original owner was a heavy or light user of the phone, might affect the value of the used phone. Additionally, Plaintiffs do not address whether loss of use of the phone should be compensable and, if so, suggest how it might be reduced to a formula-type calculation.

If courts aren’t willing to ballpark something as simple as the value of stolen phones, consumer and other class actions are in big trouble, which, of course, they already are under a growing body of legislative restrictions at both the federal and state levels. Assuming the truth of the plaintiffs’ allegations, the effect of the court’s ruling is that every person who had their phone stolen and reactivated after reporting the theft would have to bring a separate lawsuit to get relief, which, of course, isn’t going to happen because pursuing litigation is cost and time prohibitive to all but the most querulous of consumers. The threat of individual consumer lawsuits in cases that, like this one, involve small amounts of damages isn’t a realistic deterrence to corporate misconduct.

But no worries. There won’t be any individual lawsuits anyway because T-Mobile, like most corporations, requires customers to sign or click-through an agreement in which they give up their legal rights to sue in a court of law in favor of binding non-judicial arbitration. (Whether T-Mobile had waived the arbitration clause was another issue in the litigation.)

—Little v. T-Mobile, Case No. 12-10170, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, August 22, 2012. Thanks to Paul Scott.

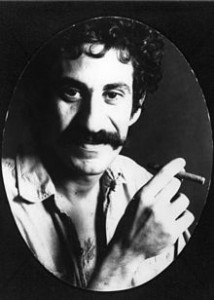

August 17th, 2012  Court of Appeals used this guy’s tunes to find humor in alleged gun assault. One rule of thumb regarding amusing judicial opinions is that the higher up the judicial hierarchy one climbs, the fewer such opinions one encounters. But here we have the distinguished U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, per Judge Ed Carnes, having fun with a case that probably wasn’t amusing from the plaintiff’s point of view, assuming the allegations of his complaint are true.

As alleged: A mother, a state corrections officer, came home in uniform to find her daughter and plaintiff engaging in intimate relations. The complaint alleges she pulled her gun on the naked plaintiff, threatened to shoot him, forced him to his knees, handcuffed him, tried to have him arrested, and further assaulted and threatened him. He was ultimately released unharmed physically.

The young man sued the mother and the county sheriff, her employer, in a Section 1983 action. The claim against the sheriff was based on the allegation the mother acted under color of state law (in an official capacity) when she allegedly assaulted the plaintiff.

The Eleventh Circuit rejected that claim, endorsing the district court’s position that the mother was no more than “an angry parent who happened to be in uniform, have handcuffs, and a firearm, which she used for the private ends of assaulting and scaring a young man she caught in bed with her daughter.”

Judge Carnes had a great time with the opinion, starting and ending with references to Jim Croce songs. Okay, this is just a wild guess, but I’m thinking Judge Carnes has never been forced naked to his knees, handcuffed, at gunpoint, by someone threatening to shoot him. Here are some excerpts (I substituted “plaintiff, “defendant,” and “defendant’s daughter” for the actors’ names):

In one of his ballads, Jim Croce warned that there are four things that you just don’t do: “You don’t tug on Superman’s cape/ You don’t spit into the wind/ You don’t pull the mask off that old Lone Ranger/ And you don’t mess around with Jim.” He could have added a fifth warning to that list: “And you don’t let a pistol-packing mother catch you naked in her daughter’s closet.”

It all started with a phone call. Nineteen-year-old defendant’s daughter called plaintiff, who was of a similar age, and invited him to her house. Plaintiff responded to the invitation the way most young men over the age of consent would have—he went. …

Then they consented to do what young couples alone in a house have been consenting to do since the memory of man (and woman) runneth not to the contrary. The record does not disclose how long these two young people had known each other in the dictionary sense, but that afternoon in … the bedroom they also knew each other in the biblical sense.

That’s when the mother came home. Discovering plaintiff with her daughter, she allegedly pulled her firearm on him. She apparently asserted that she believed the plaintiff was attacking her daughter.

She told plaintiff that if he moved or did not follow her commands, she would shoot him.

Plaintiff tried to explain that her daughter had invited him to the house, but defendant insisted that he must have broken in. She had the still-naked plaintiff turn around, she handcuffed him, and she made him get down on his knees. After staying there “for a prolonged period,” plaintiff pleaded with defendant that he could not maintain that position any longer. Defendant responded by telling him to bend over or she would shoot him. She “made numerous threats against plaintiff, telling him that she would ‘kill him’ if he did not obey her commands.”

…

The amended complaint and plaintiff’s briefs leave no doubt that he feels mistreated, and with what appears to be some justification. If the allegations are true, defendant’s treatment of plaintiff was badder than old King Kong and meaner than a junkyard dog. She might even have acted like the meanest hunk of woman anybody had ever seen. Still, the fact that the mistreatment was mean does not mean that the mistreatment was under color of law.

Glad at least someone involved in the case had fun, Judge.

–Butler v. Sheriff of Palm Beach County, Case No. 11-13933 (11th Cir., July 6, 2012). Thanks to Paul Scott.

August 11th, 2012  Banana Slugs – Mascot for U.C.-Santa Cruz [Judge Terence T. Evans, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, passed away in 2011. Here’s a nice tribute to him on the Marquette law school (where he attended law school) faculty blog.]

In an opinion involving controversy over “Chief Illiniwek,” mascot of the University of Illinois since 1926, Judge Terence Evans of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit once again showed his dominance as the nation’s premiere judicial sports buff.

A group of students and faculty who believed the mascot degraded Native Americans brought suit against the university chancellor, seeking a declaratory judgment that the chancellor’s order banning all speech directed toward prospective student athletes without prior permission violated their First Amendment rights. The students and faculty wanted to contact prospective student athletes regarding the controversy.

The court found the policy violated the plaintiffs’ rights, but before getting to the merits, Judge Evans took a substantial detour into sports mascot trivia:

In the Seventh Circuit, some large schools–Wisconsin (Badgers), Purdue (Boilermakers), Indiana (Hoosiers), Notre Dame (The Fighting Irish), DePaul (the Blue Demons), the University of Evansville (Purple Aces), and Southern Illinois (Salukis)–have nicknames that would make any list of ones that are pretty cool. And small schools in this circuit are no slouches in the cool nickname department. One would have a hard time beating the Hustlin’ Quakers of Earlham College (Richmond, Indiana), the Little Giants of Wabash College (Crawfordsville, Indiana), the Mastodons of Indiana University-Purdue University-Fort Wayne (Fort Wayne, Indiana), and the Scarlet Hawks of the Illinois Institute of Technology.

But most schools have mundane nicknames. How can one feel unique when your school’s nickname is Tigers (43 different colleges or universities), Bulldogs (40 schools), Wildcats (33), Lions (32), Pioneers (31), Panthers or Cougars (30 each), Crusaders (28), or Knights (25)? Or how about Eagles (56 schools)? The mascots for these schools, who we assume do their best to fire up the home crowd, are pretty generic–and pretty boring.

“Some schools adorn their nicknames with adjectives–like “Golden,” for instance. Thus, we see Golden Bears, Golden Bobcats, Golden Buffaloes, Golden Bulls, Golden Eagles (15 of them alone!), Golden Flashes, Golden Flyers, Golden Gophers, Golden Griffins, Golden Grizzlies, Golden Gusties, Golden Hurricanes, Golden Knights, Golden Lions, Golden Panthers, Golden Rams, Golden Seals, Golden Suns, Golden Tigers, and Golden Tornados cheering on their teams.

All this makes it quite obvious that, when considering college nicknames, one must kiss a lot of frogs to get a prince. But there are a few princes. For major universities, one would be hard pressed to beat gems like The Crimson Tide (Alabama), Razorbacks (Arkansas), Billikens [Fn.2]

[Fn.2] What in the world is a “Billiken”?

(St.Louis), Horned Frogs (TCU), and Tarheels (North Carolina). But as we see it, some small schools take the cake when it comes to nickname ingenuity. Can anyone top the Anteaters of the University of California-Irvine; the Hardrockers of the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in Rapid City; the Humpback Whales of the University of Alaska-Southeast; the Judges (we are particularly partial to this one) of Brandeis University; the Poets of Whittier College; the Stormy Petrels of Oglethorpe University in Atlanta; the Zips of the University of Akron; or the Vixens (will this nickname be changed if the school goes coed?) of Sweet Briar College in Virginia? As wonderful as all these are, however, we give the best college nickname nod to the University of California-Santa Cruz. Imagine the fear in the hearts of opponents who travel there to face the imaginatively named “Banana Slugs”?

From this brief overview of school nicknames, we can see that they cover a lot of territory, from the very clever to the rather unimaginative. But one thing is fairly clear–although most are not at all controversial, some are. Even the Banana Slug was born out of controversy. For many years, a banana slug (ariolomax dolichophalus to the work of science) was only the unofficial mascot at UC-Santa Cruz. In 1981, the chancellor named the “Sea Lion” as the school’s official mascot. But some students would have none of that. Arguing that the slug represented some of the strongest elements of the campus, like flexibility and nonagressiveness, the students pushed for and funded a referendum which resulted in a landslide win for the Banana Slug over the Sea Lion. And so it became the official mascot.

Not all mascot controversies are “fought” out as simply as was the dispute over the Banana Slug. Which brings us to the University of Illinois where its nickname is the “Fighting Illini,” a reference to a loose confederation of Algonquin Indian Tribes that inhabited the upper Mississippi Valley area when French explorers first journeyed there from Canada in the early seventeenth century. The university’s mascot, to mirror its nickname–or to some its symbol–is “Chief Illiniwek.” Chief Illiniwek is controversial. And the controversy remains unresolved today. …”

Even if you’re not a sports fan, you have to appreciate a federal appellate judge who uses phrases like “pretty cool” and “pretty boring” in his opinions. I wonder if he talked like that during oral arguments. “Counselor, that was a pretty cool motion you filed the other day, but it was pretty boring.”

R.I.P. Judge Evans. You are missed.

— Crue v. Aiken, 370 F.3d 668, 671–72 & n.2 (7th Cir. 2004). Thanks to Professor Howard Wasserman, a decent sports trivia buff in his own right.

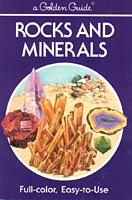

July 14th, 2012  One of Zim's classics. Remember “Golden Guides”? They were sort of the original “Dummies” series for kids, explaining a variety of scientific, geographic, and nature topics in succinct terms understandable even by 10 year olds.

Zim v. Western Pub. Co. arose out of a dispute between the guy who wrote or co-wrote many of these masterpieces—Dr. Herbert Zim—and the Golden Guides publisher, Western Publishing. Zim penned such classics as Rocks and Minerals, Reptiles and Amphibians, Trees, and my personal fav, Fishes.

Judge Goldberg of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit apparently also thinks highly of Zim, elevating him to biblical proportions:

In the beginning, Zim [Fn.1] created the concept of the Golden Guides. For the earth was dark and ignorance filled the void. And Zim said, let there be enlightenment and there was enlightenment. In the Golden Guides, Zim created the heavens (STARS) (SKY OBSERVER’S GUIDE) and the earth. (MINERALS) (ROCKS and MINERALS) (GEOLOGY).

[Fn.1] Dr. Zim is a noted science educator with a Ph.D. in science education from Columbia University. His special expertise is in the presentation of scientific subjects to popular audiences. The major focus of his efforts has been the development of a multivolume series of books on scientific subjects, the “Golden Guides.” …

And together with his publisher, Western, he brought forth in the Golden Guides knowledge of all manner of living things that spring from the earth, grass, herbs yielding seed, fruit-trees yielding fruits after their kind, (PLANT KINGDOM) (NON-FLOWERED PLANTS) (FLOWERS) (ORCHIDS) (TREES), and Zim saw that it was good. And they brought forth in the Golden Guides knowledge of all the living moving creatures that dwell in the waters, (FISHES) (MARINE MOLLUSKS) (POND LIFE), and fowl that may fly above the earth. (BIRDS) (BIRDS OF NORTH AMERICA) (GAMEBIRDS). And Zim saw that it was good. And they brought forth knowledge in the Golden Guides of the creatures that dwell on dry land, cattle, and creeping things, (INSECTS) (INSECT PESTS) (SPIDERS), and beasts of the earth after their kind. (ANIMAL KINGDOM). And Zim saw that it was very good.[Fn.4]

[Fn.4] According to Zim’s brief before this court, well over 100 million of the Golden Guide books have been printed under Zim’s name, earning him “millions of dollars” in royalties.

Then there rose up in Western a new Vice-President who knew not Zim. And there was strife and discord, anger and frustration, between them for the Golden Guides were not being published or revised in their appointed seasons. And it came to pass that Zim and Western covenanted a new covenant, calling it a Settlement Agreement. But there was no peace in the land. Verily, they came with their counselors of law into the district court for judgment and sued there upon their covenants.

And they put upon the district judge hard tasks. And the district judge listened to long testimony and received hundreds of exhibits. So Zim did cry unto the district judge that he might remember the promises of the Settlement Agreement. And the district judge heard Zim’s cry, but gave judgment for Western. Yea, the district judge gave judgment to Western on a counterclaim as well. Therefore, Zim went up out of the court of the district judge.

And Zim spake unto the Court of Appeals saying, make a sacrifice of the judgment below. And the judges, three in number, convened in orderly fashion to recount the story of the covenants and to discuss and answer the four questions which Zim brought before them …

Maybe it’s just because I loved Golden Guides, but this one goes in the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

— Zim v. Western Pub. Co., 573 F.2d 1318, 1320–21 (5th Cir. 1978). Thanks to Professor Ken Swift.

July 6th, 2012  Siskel and Kozinski? Judge Alex Kozinski, of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, was well-known for his sparkling prose in writing opinions, but his most classic opinion was U.S. v. Syufy Enterprises, in which he weaved in more than 200 movie titles.

In Syufy, the federal government sued Las Vegas movie-chain owner Syufy for antitrust violations. In affirming the trial court’s dismissal of the antitrust charges, rumor had it that Judge Kozinski wove more than 200 movie titles into the text of his fourteen-page opinion.

But did it really happen? Was it urban legend? Bourbon legend?

It really happened. Daniel Solzman of the Tarlton Library at the University of Texas law school assembled the entire list of movies Kozinski managed to cram into Syufy as part of its Law in Popular Culture Collection. Here are the movie titles in the order they appeared:

M, Suspect, Giant, Nevada, Illegal, Monkey Business, Platoon, David, 8 1/2, The Power, The Competition, Greatest Hurdle, Gone are the Days, Popcorn, Something for Everyone, Manpower, The Producers, Formula, Splash, Shame, Stir, Titanic, Easy Money, No Holds Barred, Upper Hand, Rivals, Rocky, Until September, September, Midway, The Big Picture, Do the Right Thing, Brass Knuckles, The Accused, Humongous, Little Big Man, Chances, Vice Versa, Always, Nuts, The Seven-Ups, Big, Ordinary People, Possessed, Foul Play, The Survivors, Personal Services, Time after Time, Challenge, Testimony, Riding High, Captured, Utopia, Dark Horse, Invitation, Major League, Against all Odds, Fighting Fire with Fire, Trading Places, The End, Country, Losing Ground, Short Circuit, Lock Up, Dead Heat, Personal Best, Absolute Beginners, Staying Alive, Big Business, Network, Shopworm, Witness, High Tide, The Law, Wisdom, The Hand, Guilty, Illicit, Satisfaction, The Victim, Raw Deal, The Evil, Above the Law, Down by Law, Off Limits, The Enforcer, Fear, The Villain, The Weapon, Champion, The Natural, Deliverance, The Disappearance, The Challenge, Running, The Other, Top Gun, Players, The Trial, Paid, Head, The Squeeze, Seven Days, Cold Feet, Gambit Backfire, Contract, Cold Turkey, Lost, Plenty, After Hours, The Judge, The Trap, Leviathan, Stick, Tough Enough, Making It, Risky Business, Squeeze Play, Sitting Ducks, Boomerang, Big Trouble, The Principal, House of Cards, Tribute, America, Target, Paper Tiger, Distance, Local Hero, Being There, Fire Sale, Abandoned, The Lawyer, You and Me, Avalanche, Surrender, The First Time, Hard Choices, Showdown, Fail-Safe, The Great Race, Relentless, The Fountainhead, Out, House, Volunteers, October, 1984, Over the Top, Ran, Trapped, The Gate, Hard Times, Partners, California, Barrier, Five, Colors, Exposed, Switching Channels, Checking Out, Fame, Great Expectations, Without a Trace, Perfect, Out of Bounds, Offbeat, Critic’s Choice, The Longshot, The Sure Thing, Misunderstood, Boom Town, Static, Alien, Things Change, High Hopes, The Jackpot, Drive-in, Performance, New Faces, The Thing, The Crucible, Violated, All the Right Moves, The Creator, Interiors, Clue, Fashion, Winner Take All, Any Number Can Play, Insignificance, The Harder They Fell, Missing, Shakedown, Ruthless Predator, Dangerous, Critical Condition.

Kozinski never confirmed or denied the rumors about intentionally loading up Syufy with movie titles.

— United States v. Syufy Enterprises, Inc., 903 F.2d 659 (9th Cir. 1990); see also The Syufy Rosetta Stone, 1992 BYU L. Rev. 457 (1992).

June 24th, 2012 Maybe there should be an opposite abbreviation to TMI such as NEI (not enough information).

In a case involving a challenge to nuclear waste fees at a site intended to replace the Yucca Mountain disposal site, brought to our attention by way of The BLT: The Blog of LegalTimes, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia admonished the lawyers – in the attention-stealing first footnote no less – for using too many acronyms:

1. We also remind the parties that our Handbook of Practice and Internal Procedures states that “parties are strongly urged to limit the use of acronyms” and “should avoid using acronyms that are not widely known.” Brief-writing, no less than “written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble.” George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language,” 13 Horizon 76 (1946). Here, both parties abandoned any attempt to write in plain English, instead abbreviating every conceivable agency and statute involved, familiar or not, and littering their briefs with references to “SNF,” “HLW,” “NWF,” “NWPA,” and “BRC” – shorthand for “spent nuclear fuel,” “highlevel radioactive waste,” the “Nuclear Waste Fund,” the Nuclear Waste Policy Act,” and the “Blue Ribbon Commission.”

Who knew there was a written court rule against acronyms or that George Orwell gave legal-writing advice?

— Nat’l Ass’n of Regulatory Utility Commissioners v. U.S. Dep’t of Energy, Case No. 11-1066 (D.C. Cir., June 1, 2012)

June 17th, 2012  Whatever happened to “Appellant wins”? Back in 2003, in McConnell v. Federal Election Committee, the U.S. Supreme Court cleared up a major legal dispute over campaign financing. Er, well, maybe not completely cleared up.

The basic question was whether the McCain-Feingold Act, a federal statute that imposed restrictions on political contributions, violated the First Amendment free speech rights of potential contributors. A challenging issue no doubt, but certainly not too tough for the mighty U.S. Supreme Court to resolve, right?

With nine justices voting, the result could have been as simple as 8-1, 7-2, 6-3, or 5-4 in favor of one side or the other. The nine wise ones chose a slightly more complicated path. Here is the Court’s actual voting lineup straight out of the case:

STEVENS and O.CONNOR, JJ., delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to BCRA Titles I and II, in which SOUTER, GINSBURG, and BREYER, JJ., joined. REHNQUIST, C. J., delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to BCRA Titles III and IV, in which O.CONNOR, SCALIA, KENNEDY, and SOUTER, JJ., joined, in which STEVENS, GINSBURG, and BREYER, JJ., joined except with respect to BCRA § 305, and in which THOMAS, J., joined with respect to BCRA §§ 304, 305, 307, 316, 319, and 403(b). BREYER, J., delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to BCRA Title V, in which STEVENS, O.CONNOR, SOUTER, and GINSBURG, JJ., joined. SCALIA, J., filed an opinion concurring with respect to BCRA Titles III and IV, dissenting with respect to BCRA Titles I and V, and concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part with respect to BCRA Title II. THOMAS, J., filed an opinion concurring with respect to BCRA Titles III and IV, except for BCRA §§ 311 and 318, concurring in the result with respect to BCRA § 318, concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part with respect to BCRA Title II, and dissenting with respect to BCRA Titles I, V, and § 311, in which opinion SCALIA, J., joined as to Parts I, II.A, and II.B. KENNEDY, J., filed an opinion concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part with respect to BCRA Titles I and II, in which REHNQUIST, C. J.,joined, in which SCALIA, J., joined except to the extent the opinion upholds new FECA § 323(e) and BCRA § 202, and in which THOMAS, J., joined with respect to BCRA §213. REHNQUIST, C. J., filed an opinion dissenting with respect to BCRA Titles I and V, in which SCALIA and KENNEDY, JJ., joined. STEVENS, J., filed an opinion dissenting with respect to BCRA § 305, in which GINSBURG and BREYER, JJ., joined.

Who won? I have no idea.

For embodying in a single voting lineup the reason why the most accurate answer to most legal questions is “It depends,” this case gets into the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame. If members of the world’s most powerful tribunal are unable to agree on what the law means, how could one expect poor law students to do so?

— McConnell v. Federal Election Comm’n, 540 U.S. 93 (2003). Thanks to Elise Hendricks.

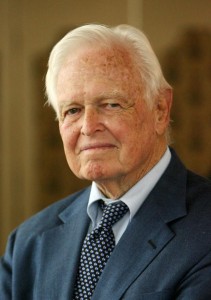

June 9th, 2012  Former Michigan Supreme Court Justice Eugene F. Black Thanks to Graham Bateman for turning Lawhaha.com on to a real character: Justice Eugene F. Black, a judge whose inflammatory dissent-writing makes caustic U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissents read like love letters in comparison.

Black regularly lashed out at his colleagues on the Michigan Supreme Court, on which he served from 1956-72, holding their feet to the fire when he saw their actions as reckless, destructive, deceptive, partisan, or willful.

For being so outrageous in his outrage, and for having such a sharp, articulate poison pen, Justice Black lands in the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

Black was a judge who took to heart the words of Benjamin Cardozo’s famous ode to dissent-writing, which Black quoted in Guilmet v. Campbell, 188 N.W.2d 601, 611 (Mich. 1971):

Comparatively speaking at least, the dissenter is irresponsible. The spokesman of the court is cautious, timid, fearful of the vivid word, the heightened phrase … Not so, however, the dissenter. He has laid aside the role of the hierophant, which he will be only too glad to resume when the chances of war make him the spokesman of the majority. For the moment, he is the gladiator making a last stand among the lions. (From Selected Writings of Benjamin Nathan Cardozo 353 (Fallon Publications 1947))

Justice Black may have been a gladiator, but I suspect his colleagues had a few other names for him. He wasn’t satisfied to simply disagree in his dissents. He liked to rip his colleagues to shreds in the process. Guilmet provides a good example. The majority held in favor of the plaintiff in a breach of contract action against a surgeon. Black’s dissent began like this:

In these early weeks of 1971 an exuberant new majority of a once great appellate court prepares to launch an unwarned, unprecedented, wholly gratuitous and destructively witless war of “contract liability” upon a brother profession ….

He was just getting warmed up. A little later, he said:

As against this there is no pretense of proffered authority or precedent. My Brothers five just say “This is the law.” That they do with an arrantly dixitized vengeance, for all of the skilled research clerks of Lansing, working with no surcease and without food or drink, never could come up with any kind of respectable or even plausible authority [for the court’s holding].

And then later:

Thus far there appears to the writer still another like bushment the Court should see but does not see, or perhaps is too absorbed to see, dead ahead.

Other examples of Justice Black’s unique style of brethrenly love include:

In re Apportionment of State Legislature, 197 N.W.2d 249, 262 (Mich. 1972) (Black, J., dissenting) (“[T]oo much of that heady stuff known as partisan politics has been steamed into the present proceeding and … this partisan-nominated Court should disqualify itself ….”)

Plumley v. Klein, 199 N.W.2d 169, 173 (Mich. 1972) (Black, J., dissenting) (“The Court has chosen the sleaziest of pleaded causes as opportune for the nullification of [a prior case.] … I cannot hold still before this latest judicial monster.”)

Jones v. Bloom, 200 N.W.2d 196, 207–08 (Mich. 1971) (“[O]ur majority must have labored, conferred, caucused and searched … to find some or any colorable way to overrule [jury’s verdict] … Our reports … are on the shelves of thousands of lawyers and judges. They bear now undeniable witness of both a profaning and deplorable fact; that this temporally seated and largely fledgling Court is bent purposefully upon progressive destruction of all or near all of the great canons and precedential precept which the nationally revered Cooley Court, and the succeeding Fellows Court, have bequeathed to Michigan.”)

Don’t know the merits of any of these cases, but in a day of cautious and tepid judges, you gotta love a judge who was willing to tell it like is (at least as he saw it).

— Citations included in text above. Thanks to Graham Bateman.

June 3rd, 2012  Triple Crown threat Funny Cide caught up in weird judicial opinion. The total weirdness of Florida Court of Appeals Judge Farmer’s opinion in Funny Cide Ventures, LLC v. Miami Herald Publ’g Co. gets the case into Lawhaha.com’s Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

Here’s a first in judicial writing: an appellate judge writes an opinion in an offbeat fiction-style based on a tune from Guys and Dolls, can’t get the other judges to go along with his approach, so decides to attach his creative opinion to the court’s per curiam opinion together with a lengthy preface explaining his unique approach to written adjudication.

Confused? Let’s back up. In 2003, Funny Cide won both the Kentucky Derby and the Preakness, one race away from the Triple Crown.

After the Kentucky Derby, the Miami Herald published an article implying that the jockey cheated by using some kind of illegal battery-powered device during the race. The Herald later admitted it made an error and retracted the story. Meanwhile, Funny Cide placed third at the Belmont, missing out on becoming only the twelfth horse in history to win the Triple Crown.

In a lawsuit for injurious falsehood against the Herald, Funny Cide’s owners claimed the article caused substantial damage, including the chance to win the Belmont because “the article caused the jockey to over-ride the horse in the Preakness in an attempt to vindicate himself.”

The defendant moved for summary judgment, which was granted on the ground that the plaintiffs had not alleged direct and immediate damages from the article. The appellate court affirmed in a brief per curiam opinion.

So far, so good.

Then the reader stumbles on Judge Farmer’s … not sure what to call it … tacked on at the end of the court’s opinion. It’s not a concurring or dissenting opinion, and is not labeled as an appendix.

His “attachment” to the majority opinion is not a dissent from the reasoning of his brethren’s opinion, but the boring way in which they expressed it.

Judge Farmer starts by assailing traditional stilted judicial opinion writing, then explains why a humanized, pot-boiler narrative approach might be better. He concludes by suggesting readers compare the two approaches–his and the majority’s–and decide which is better.

Basically, he seemed to be saying: “Hey, I labored over writing this really fun and wild opinion, but these dudes I work with on the court are too straitlaced to get it, so here it is for your reading pleasure.”

Here are excerpts, first, from his attack on traditional judicial opinion writing:

Most [judicial opinions are] … dreary and tedious. …

A surprising number are way too long. There is often a painstaking account of background and trial which turns out to be unnecessary to grasp the essential issues to be decided. Many have extended discussions of rules and principles no one really challenges, or few would dispute. Judges pile on needless details of date, time and place, modified by confusing identifying terms (appellant-cross appellee-defendant) without regard to clarity. Extended comparative quotations alternate with exposition of one sort or another. Legal issues are analyzed through mind-numbing, many-factored “tests”. Each factor is unloaded nit by nit, as though the judges actually decided the dispute in precisely that way. Arcane legal terminology is woven in and out, even though simpler, plainer words could be used. Simplicity, tone, style, voice, personality, levity-all are shunned.

Judge Farmer concedes he’s been guilty of what he describes, then sets out to change his opinion-writing ways:

From the very moment of my appointment as a judge, I have chafed under this norm for appellate opinion writing. How did it become conventional? Who made it required? Why hasn’t it been changed?

I struggled against it. There must be other styles, different tones, alternate voices. Not for every opinion. But for some.

One technique occurred to me. This idea would have an opinion in some of the forms, styles and characteristics associated with fiction. Good fiction is set in human experience. Good fiction illuminates.

***

I had decided that the style of some opinions could-and should-be unconventionally changed for greater openness to all readers. I would try to write some opinions in styles and tones calculated to make legal reasoning clearer for those without law degrees. Then came this case.

When the panel conferred after oral argument, I did not detect any disagreement. … So after thinking on the matter, I conceived of an unconventional approach. I would try a style, a tone, a voice to make apparent even to non-lawyers what I believed is the basic defect in their argument. The very style of the opinion itself would illuminate the legal analysis and outcome.

As it turns out, the other two members of the panel could not endorse the opinion or even some slightly altered version. They had concerns. Some other judges shared them. So I give this explanation for what I wrote, laying my version along side the panel’s substitute. Readers can compare a conventional opinion with an unconventional style-the pious with the impious.

Then comes the opinion. Here’s an excerpt, inspired by the opening song of Guys and Dolls, Fugue for the Tinhorns:

Then the horse won the Preakness Stakes. And it’s not even close. Wins by nearly ten lengths. The horse is so far out front, looks like he could make it past the wire and into the barn before they can take the photo. Hardly anyone asked if the horse ran out of gas for the Belmont. Are you kidding? Racing was all stirred up about the Crown. The feedbox noise grew hot.

Was it a dream, or did I hear stories about a guy who read in the paper the horse wins it all by a half? About another guy who said it was no bum steer, it was from a handicapper that’s real sincere? Even about a third guy who knew this is the horse’s time because his father’s jockey’s brother’s a friend?

Whatever. It’s a lock. Two jewels for the Crown. Make room for the third.

Only, wait a minute. Did I hear another story about this one guy who wasn’t so sure? Said it all depends if it rained last night?

For the life of me, I can’t understand why the other judges on the panel were hesitant to join in this opinion.

— Funny Cide Ventures, LLC v. Miami Herald Publ’g Co., 955 So.2d 1241, 1243–47 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2007). Thanks to Kevin McDowell and James Heelan.

May 27th, 2012  Bird expert "thinks" this might be a bird. In U.S. v. Byrnes, the defendant was convicted of making false statements to a grand jury investigating illegal trafficking in exotic birds. The issue involved the materiality of statements as to whether some illegally imported swans and geese were dead or live when the defendant received them.

To bolster its case, the government called a collector of Australian parrots who testified the defendant had delivered some swans and geese to her. Defense counsel cross-examined the witness, an immigrant from Germany who had difficulty speaking English, in an apparent effort to challenge her credibility as a bird expert. Here’s the interesting colloquy:

Q. Mrs. Meffert, do you recall testifying yesterday about your definition of birds?

A. Yes.

Q. And do you recall that you said that the swans and geese were not birds?

A. Not to me.

Q. What do you mean by that, “not to me?”

A. By me, the swans are waterfowls.

Shortly thereafter, Mrs. Meffert was cross examined as follows:

Q. Are sparrows birds?

A. I think so, sure.

Q. Is a crow a bird?

A. I think so.

Q. Is a parrot a bird?

A. Not to me.

Q. How about a seagull, is that a bird?

A. To me it is a seagull, I don’t know what it is to other people.

Q. Is it a bird to you as well or not?

A. To me it is a seagull. I don’t know any other definition for it.

Q. Is an eagle a bird?

A. I guess so.

Q. Is a swallow a bird?

A. I don’t know what a swallow is, sir.

Q. Is a duck a bird?

A. Not to me, it is a duck.

Q. But not a bird.

A. No, to other people maybe.

The government stipulated that swans and geese are birds.

Because it makes me laugh every time I read it, this opinion gains entry to the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

— United States v. Byrnes, 644 F.2d 107, 110 n.7 (2nd Cir. 1981). Thanks to Walter Fitzpatrick.

May 11th, 2012 U.S. Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Terence T. Evans, who passed away in 2011, was well-known for his opinions jammed with sports trivia (see here and here).

But in a criminal case involving witness tampering and “too many Murphys” (the defendant, his son and the trial judge were all named Murphy), Judge Evans mined a different pop culture-vein in an opening footnote necessitated by a court reporting error in the trial transcript:

1. The trial transcript quotes Ms. Hayden as saying Murphy called her a snitch bitch “hoe.” A “hoe,” of course, is a tool used for weeding and gardening. We think the court reporter, unfamiliar with rap music (perhaps thankfully so), misunderstood Hayden’s response. We have taken the liberty of changing “hoe” to “ho,” a staple of rap music vernacular as, for example, when Ludacris raps “You doin’ ho activities with ho tendencies.”

Give credit to Ludacris. Cited as authority by the distinguished U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. Maybe his next release will be a hornbook.

— United States v. Murphy, 406 F.3d 857, 859 n.1 (7th Cir. 2005). Thanks to the several folks who sent this opinion.

April 7th, 2012

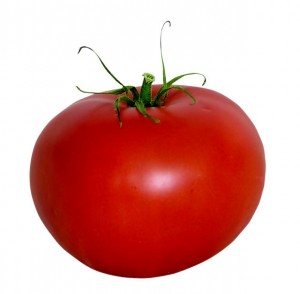

It's official. Tomatos are vegetables according to the Supreme Court. The next time someone raises the age-old debate as to whether a tomato is a fruit or a vegetable, show off your legal acuity (or nerdiness) by informing them you have it on good authority that tomatos are vegetables. No, in fact, make that great authority. Who? The U.S. Supreme Court.

More than 100 years ago, in Nix v. Hedden, Justice Horace Gray, speaking on behalf of a unanimous Supreme Court, ruled that a tomato is a vegetable as a matter of law.

The Tariff Act of 1883 declared a 10 percent duty on all vegetables entering the country, but allowed fruit to enter duty-free. The New York Customs Collector saw an opportunity to increase revenue and declared the tomato to be a vegetable.

Angry importers sued and their case reached the Supreme Court, where Justice Gray said: “[A]lthough botanists consider the tomato a fruit, tomatoes are eaten as a principal part of a meal, like squash or peas, (and all grow on vines), so it is the court’s decision that the tomato is a vegetable.”

— Nix v. Hedden, 149 U.S. 304 (1893). Thanks to Lihwei Lin.

April 4th, 2012  “Excuse me, I’d like to have a few words with you about the litter box issue.” Miles v. City Council of Augusta, GA—starring “Blackie the Talking Cat”—is our kind of case: completely WEIRD, so weird that it qualifies for Lawhaha.com’s Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

The plaintiffs, Carl and Elaine Mills, were an unemployed, married couple who owned Blackie, a cat who could allegedly speak English. The plaintiffs were entrepreneurs in the true American mold, making their entire living marketing Blackie’s unique vocal abilities to the public. Although the closest Blackie ever came to making the big time was a $500 appearance on “That’s Incredible” in 1980, he generated steady income for Carl and Elaine by talking to strangers on the street in return for contributions.

After receiving complaints, the Augusta Police Department warned Carl and Elaine that they needed to obtain a business license to continue peddling Blackie’s talents on the streets of Augusta. Plaintiffs sued the city, alleging the occupational license tax was unconstitutional.

The whole opinion is interesting, but the craziest part was the trial judge’s disclosure in a footnote of an ex parte street encounter with Blackie (some paragraph breaks inserted):

In ruling on the motions for summary judgment, the Court has considered only the evidence in the file. However, it should be disclosed that I have seen and heard a demonstration of Blackie’s abilities.

The point in time of the Court’s view was late summer, 1982, well after the events contended in this lawsuit. One afternoon when crossing Greene Street in an automobile, I spotted in the median a man accompanied by a cat and a woman. The black cat was draped over his shoulder. Knowing the matter to be in litigation, and suspecting the cat was Blackie, I thought twice before stopping. Observing, however, that counsel for neither side was present and that any citizen on the street could have happened by chance upon this scene, I spoke, and the man with the cat eagerly responded to my greeting.

I asked him if his cat could talk. He said he could, and if I would pull over on the side street he would show me. I did, and he did. The cat was wearing a collar, two harnesses and a leash. Held and stroked by the man Blackie said “I love you” and “I want my Mama.”

The man then explained that the cat was the sole source of income for him and his wife and requested a donation which was provided. I felt that my dollar was well spent …

I never understood why a cat that could talk didn’t become more famous.

— Miles v. City Council of Augusta, Ga., 551 F. Supp. 349, 350 n.1 (S.D. Ga. 1982). Thanks to Richard McKewen.

April 1st, 2012 A pro se litigant in Arkansas appealed a trial court decision granting custody of her child to the biological father and ordering that the child’s birth name be changed. The trial court granted the custody change and ordered the child’s name be changed to “Samuel Charles.” Not a bad name, but why order a change? Personally, I liked the original name: “Weather’By Dot Com Chanel Fourcast.”

For making us laugh out loud, this order gets into the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

Here’s the colloquy in which the perplexed trial judge asked the mother to explain the child’s birth name:

The Court: I simply do not understand why you named this child — his legal name is Weather’By Dot Com Chanel Fourcast Sheppard. Now, before you answer that, Mr. – the plaintiff in this action is a weatherman for a local television station?

Sheppard: Yes.

The Court: Okay. Is that why you named this child the name that you gave the child?

Sheppard: It – it stems from a lot of things.

The Court: Okay. Tell me what they are.

Sheppard: Weather’by — I’ve always heard of Weatherby as a last name and never a first name, so I thought Weatherby would be — and I’m sure you could spell it b-e-e or b-e-a or b-y. Anyway, Weatherby.

The Court: Where did you get the “Dot Com”?

Sheppard: Well, when I worked at NBC, I worked on a Teleprompter computer.

The Court: All right.

Sheppard: All right, and so that’s where the Dot Com [came from]. I just thought it was kind of cute, Dot Com, and then instead of — I really didn’t have a whole lot of names because I had nothing to work with. I don’t know family names. I don’t know any names of the Speir family, and I really had nothing to work with, and I thought “Chanel”? …

The Court: Well, where did you get “Fourcast”?

Sheppard: Fourcast? Instead of F-o-r-e, like your future forecast or your weather forecast, F-o-u, as in my fourth son, my fourth child, Fourcast. It was —

The Court: So his name is Fourcast, F-o-u-r-c-a-s-t?

Sheppard: Yes.

The Court: All right. Now, do you have some objection to him being renamed Samuel Charles?

Sheppard: Yes.

The Court: Why? You think it’s better for his name to be Weather’by Dot Com Chanel —

Sheppard: Well, the —

The Court: Just a minute for the record.

Sheppard: Sorry.

The Court: Chanel Fourcast, spelled F-o-u-r-c-a-s-t? And in response to that question, I want you to think about what he’s going to be — what his life is going to be like when he enters the first grade and has to fill out all [the] paperwork where you fill out — this little kid fills out his last name and his first name and his middle name, okay? So I just want – if your answer to that is yes, you think his name is better today than it would be with Samuel Charles, as his father would like to name him and why. Go ahead.

Sheppard: Yes, I think it’s better this way.

The Court: The way he is now?

Sheppard: Yes. He doesn’t have to use “Dot Com.” I mean, as a grown man, he can use whatever he wants.

The Court: As a grown man, what is his middle name? Dot Com Chanel Fourcast?

Sheppard: He can use Chanel, he can use the letter “C.”

The Court: And when he gives his Birth Certificate — is it on his birth certificate as you’ve stated to the Court? Does his Birth — does this child’s Birth Certificate read “Weather’by Dot com” —

Sheppard: That’s how I filled out the paperwork for his —

The Court: — Chanel Fourcast?

Sheppard: Yes, and for his Social Security card, I filled it out as Weather’by F. Sheppard.

The Court: All right.

The Arkansas court of appeals upheld the trial judge’s ruling based largely on its finding that the birth name could subject the child to embarrassment.

— Sheppard v. Speir, 157 S.W.3d 583, 587–88 (Ark. Ct. App. 2004). Thanks to David Eanes.

February 18th, 2012  Congratulations to the new parents. The Court so orders. In a Kansas federal district court, the defendants’ lawyer asked for a trial continuance because it conflicted with the date on which his wife was having a baby.

The plaintiffs’ lawyers opposed the continuance, which “surprised” the judge. “Irritated” is probably more accurate. Judge Eric Melgren not only granted the motion for continuance, but chastised the objecting lawyers while ordering that the new parents be congratulated:

Defendants seek a brief continuance, noting that one of their counsel …, along with his wife, is expecting their first child due on July 3. Given the proposed length of trial and the famous disregard that newborns (especially first-borns) have for such schedules, and given that the trial is scheduled in Kansas City while the new [baby’s] arrival is scheduled in Dallas, Defendants move this Court for a continuance.

This in itself would not be remarkable, but in reviewing the motion the Court was more than somewhat surprised to read that “Plaintiffs have refused to agree to continue the trial setting and have indicated that they intend to oppose this Motion.”

Well, every party is entitled to file an opposition to a motion, and hoping that perhaps Defendants’ had mis-characterized the vigor of Plaintiffs’ opposition, we have eagerly awaited Plaintiffs’ defense of its opposition. The Memorandum in Opposition arrived yesterday, and it was, sadly, as advertised.

First, Plaintiffs make a lengthy and spirited argument about when Defendants should have known this would happen, even citing a pretrial conference occurring in early November as a time when [Plantiffs’ lawyer] “most certainly” would have known of the due date of his child, and even more astonishingly arguing that “utilizing simple math, the due date for [the] child’s birth would have been known on approximately Oct. 3, or shortly thereafter.”

For reasons of good taste which should be (though, apparently, are not) too obvious to explain, the Court declines to accept Plaintiffs’ invitation to speculate on the time of conception of the … child.