October 26th, 2012  In this Halloween-themed case, the plaintiff bought a house, only to learn that it had a reputation in the Village of Nyack, NY, for being possessed by poltergeists, a reputation built in large part on the seller’s previous efforts to promote the house as haunted, which were unknown to plaintiff. On learning of the alleged haunting, plaintiff sued for rescission of the sale contract. In this Halloween-themed case, the plaintiff bought a house, only to learn that it had a reputation in the Village of Nyack, NY, for being possessed by poltergeists, a reputation built in large part on the seller’s previous efforts to promote the house as haunted, which were unknown to plaintiff. On learning of the alleged haunting, plaintiff sued for rescission of the sale contract.

The New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division, over one dissent, ruled for the plaintiff, going against the usual rule in New York of strict caveat emptor (let the buyer beware), which imposed no duty on house sellers to disclose even known defects. Based on the seller’s previous assertions that the house was haunted, the court said the seller was estopped from claiming otherwise and that the house was haunted “as a matter of law.”

So New York property owners take note: there is no duty to report collapsing roofs, faulty foundations, or termite infestations, but, after this opinion, suspected poltergeist infestations must be disclosed. (The case was decided in 1991; New York may have modified its caveat emptor rule since then.)

We’ll let the court–per Judge Rubin–unravel this hair-raiser. Turn the lights low, cuddle up, and prepare for the one and only judicial ghost story, a classic tale of a stranger arriving in a town where things aren’t quite what they seem. [Cue spooky music]:

The unusual facts of this case … clearly warrant a grant of equitable relief to the buyer who, as a resident of New York City, cannot be expected to have any familiarity with the folklore of the Village of Nyack. Not being a “local,” plaintiff could not readily learn that the home he had contracted to purchase is haunted.

Whether the source of the spectral apparitions seen by defendant seller are parapsychic or psychogenic, having reported their presence in both a national publication (“Readers’ Digest”) and the local press …, defendant is estopped to deny their existence and, as a matter of law, the house is haunted.

More to the point, however, no divination is required to conclude that it is defendant’s promotional efforts in publicizing her close encounters with these spirits which fostered the home’s reputation in the community. In 1989, the house was included in a five-home walking tour of Nyack and described in a November 27th newspaper article as “a riverfront Victorian (with ghost).” The impact of the reputation thus created goes to the very essence of the bargain between the parties, greatly impairing both the value of the property and its potential for resale. ….

While I agree… that the real estate broker, as agent for the seller, is under no duty to disclose to a potential buyer the phantasmal reputation of the premises and that, in his pursuit of a legal remedy for fraudulent misrepresentation against the seller, plaintiff hasn’t a ghost of a chance, I am nevertheless moved by the spirit of equity to allow the buyer to seek rescission of the contract of sale and recovery of his down payment.

New York law fails to recognize any remedy for damages incurred as a result of the seller’s mere silence, applying instead the strict rule of caveat emptor. Therefore, the theoretical basis for granting relief, even under the extraordinary facts of this case, is elusive if not ephemeral.

“Pity me not but lend thy serious hearing to what I shall unfold” (William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act I, Scene V [Ghost] ).

From the perspective of a person in the position of plaintiff herein, a very practical problem arises with respect to the discovery of a paranormal phenomenon: “Who you gonna’ call?” as the title song to the movie “Ghostbusters” asks. Applying the strict rule of caveat emptor to a contract involving a house possessed by poltergeists conjures up visions of a psychic or medium routinely accompanying the structural engineer and Terminix man on an inspection of every home subject to a contract of sale.

It portends that the prudent attorney will establish an escrow account lest the subject of the transaction come back to haunt him and his client–or pray that his malpractice insurance coverage extends to supernatural disasters.

In the interest of avoiding such untenable consequences, the notion that a haunting is a condition which can and should be ascertained upon reasonable inspection of the premises is a hobgoblin which should be exorcised from the body of legal precedent and laid quietly to rest.

The court detailed New York’s strict caveat emptor rule, but ultimately couldn’t stomach the fact that it was the defendant who, in effect, created the defect by broadcasting the house’s haunted status, thereby impairing its value:

In the case at bar, defendant seller deliberately fostered the public belief that her home was possessed. … Where, as here, the seller not only takes unfair advantage of the buyer’s ignorance but has created and perpetuated a condition about which he is unlikely to even inquire, enforcement of the contract (in whole or in part) is offensive to the court’s sense of equity. Application of the remedy of rescission, within the bounds of the narrow exception to the doctrine of caveat emptor set forth herein, is entirely appropriate to relieve the unwitting purchaser from the consequences of a most unnatural bargain.

The dissenting judge wanted to stick with the caveat emptor rule, stating that “if the doctrine of caveat emptor is to be discarded, it should be for a reason more substantive than a poltergeist.”

–Stambovsky v. Ackley,169 A.D.2d 254 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1991)

April 4th, 2012  “Excuse me, I’d like to have a few words with you about the litter box issue.” Miles v. City Council of Augusta, GA—starring “Blackie the Talking Cat”—is our kind of case: completely WEIRD, so weird that it qualifies for Lawhaha.com’s Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

The plaintiffs, Carl and Elaine Mills, were an unemployed, married couple who owned Blackie, a cat who could allegedly speak English. The plaintiffs were entrepreneurs in the true American mold, making their entire living marketing Blackie’s unique vocal abilities to the public. Although the closest Blackie ever came to making the big time was a $500 appearance on “That’s Incredible” in 1980, he generated steady income for Carl and Elaine by talking to strangers on the street in return for contributions.

After receiving complaints, the Augusta Police Department warned Carl and Elaine that they needed to obtain a business license to continue peddling Blackie’s talents on the streets of Augusta. Plaintiffs sued the city, alleging the occupational license tax was unconstitutional.

The whole opinion is interesting, but the craziest part was the trial judge’s disclosure in a footnote of an ex parte street encounter with Blackie (some paragraph breaks inserted):

In ruling on the motions for summary judgment, the Court has considered only the evidence in the file. However, it should be disclosed that I have seen and heard a demonstration of Blackie’s abilities.

The point in time of the Court’s view was late summer, 1982, well after the events contended in this lawsuit. One afternoon when crossing Greene Street in an automobile, I spotted in the median a man accompanied by a cat and a woman. The black cat was draped over his shoulder. Knowing the matter to be in litigation, and suspecting the cat was Blackie, I thought twice before stopping. Observing, however, that counsel for neither side was present and that any citizen on the street could have happened by chance upon this scene, I spoke, and the man with the cat eagerly responded to my greeting.

I asked him if his cat could talk. He said he could, and if I would pull over on the side street he would show me. I did, and he did. The cat was wearing a collar, two harnesses and a leash. Held and stroked by the man Blackie said “I love you” and “I want my Mama.”

The man then explained that the cat was the sole source of income for him and his wife and requested a donation which was provided. I felt that my dollar was well spent …

I never understood why a cat that could talk didn’t become more famous.

— Miles v. City Council of Augusta, Ga., 551 F. Supp. 349, 350 n.1 (S.D. Ga. 1982). Thanks to Richard McKewen.

April 1st, 2012 A pro se litigant in Arkansas appealed a trial court decision granting custody of her child to the biological father and ordering that the child’s birth name be changed. The trial court granted the custody change and ordered the child’s name be changed to “Samuel Charles.” Not a bad name, but why order a change? Personally, I liked the original name: “Weather’By Dot Com Chanel Fourcast.”

For making us laugh out loud, this order gets into the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

Here’s the colloquy in which the perplexed trial judge asked the mother to explain the child’s birth name:

The Court: I simply do not understand why you named this child — his legal name is Weather’By Dot Com Chanel Fourcast Sheppard. Now, before you answer that, Mr. – the plaintiff in this action is a weatherman for a local television station?

Sheppard: Yes.

The Court: Okay. Is that why you named this child the name that you gave the child?

Sheppard: It – it stems from a lot of things.

The Court: Okay. Tell me what they are.

Sheppard: Weather’by — I’ve always heard of Weatherby as a last name and never a first name, so I thought Weatherby would be — and I’m sure you could spell it b-e-e or b-e-a or b-y. Anyway, Weatherby.

The Court: Where did you get the “Dot Com”?

Sheppard: Well, when I worked at NBC, I worked on a Teleprompter computer.

The Court: All right.

Sheppard: All right, and so that’s where the Dot Com [came from]. I just thought it was kind of cute, Dot Com, and then instead of — I really didn’t have a whole lot of names because I had nothing to work with. I don’t know family names. I don’t know any names of the Speir family, and I really had nothing to work with, and I thought “Chanel”? …

The Court: Well, where did you get “Fourcast”?

Sheppard: Fourcast? Instead of F-o-r-e, like your future forecast or your weather forecast, F-o-u, as in my fourth son, my fourth child, Fourcast. It was —

The Court: So his name is Fourcast, F-o-u-r-c-a-s-t?

Sheppard: Yes.

The Court: All right. Now, do you have some objection to him being renamed Samuel Charles?

Sheppard: Yes.

The Court: Why? You think it’s better for his name to be Weather’by Dot Com Chanel —

Sheppard: Well, the —

The Court: Just a minute for the record.

Sheppard: Sorry.

The Court: Chanel Fourcast, spelled F-o-u-r-c-a-s-t? And in response to that question, I want you to think about what he’s going to be — what his life is going to be like when he enters the first grade and has to fill out all [the] paperwork where you fill out — this little kid fills out his last name and his first name and his middle name, okay? So I just want – if your answer to that is yes, you think his name is better today than it would be with Samuel Charles, as his father would like to name him and why. Go ahead.

Sheppard: Yes, I think it’s better this way.

The Court: The way he is now?

Sheppard: Yes. He doesn’t have to use “Dot Com.” I mean, as a grown man, he can use whatever he wants.

The Court: As a grown man, what is his middle name? Dot Com Chanel Fourcast?

Sheppard: He can use Chanel, he can use the letter “C.”

The Court: And when he gives his Birth Certificate — is it on his birth certificate as you’ve stated to the Court? Does his Birth — does this child’s Birth Certificate read “Weather’by Dot com” —

Sheppard: That’s how I filled out the paperwork for his —

The Court: — Chanel Fourcast?

Sheppard: Yes, and for his Social Security card, I filled it out as Weather’by F. Sheppard.

The Court: All right.

The Arkansas court of appeals upheld the trial judge’s ruling based largely on its finding that the birth name could subject the child to embarrassment.

— Sheppard v. Speir, 157 S.W.3d 583, 587–88 (Ark. Ct. App. 2004). Thanks to David Eanes.

November 27th, 2011  More appropriate publication vehicle than the Northeast Reporter? A lawsuit brought by a woman who got a fishbone lodged in her throat while eating a bowl of fish chowder at a Boston restaurant moved the Massachusetts Supreme Court to write an opinion devoted more to the joys of New England fish recipes than actual law.

The legal dispute is an old one: To what extent is food containing a harmful ingredient a defective product when the substance is a natural one as opposed to a foreign one?

Most modern courts apply a reasonableness test that looks at whether the substance was one a consumer would reasonably expect to find in a prepared dish, but the Massachusetts Supreme Court in this 1964 case adopted the older approach that there is no liability for harm-causing natural substances (i.e., bones as opposed to pieces of glass) in food.

Reading the opinion, it wasn’t hard to predict the defendant was going to win in the end. The court reminisced fondly about the history of fish dishes, recounted several recipes for the same, and included statements such as “we consider that the joys of life in New England include the ready availability of fresh fish chowder.”

The court went so far as to note that “[a] namesake of the plaintiff, Daniel Webster, had a recipe for fish chowder which has survived into a number of modern cookbooks and in which the removal of fish bones is not mentioned at all.”

The court concluded:

[W]e consider a dish which for many long years, if well made, has been made generally as outlined above. It is not too much to say that a person sitting down in New England to consume a good New England fish chowder embarks on a gustatory adventure which may entail the removal of some fish bones from his bowl as he proceeds. We are not inclined to tamper with age old recipes by any amendment reflecting the plaintiff’s view of the effect of the Uniform Commercial Code upon them.

This is a must-read opinion for all products liability lawyers and anyone looking for a good fish-chowder recipe.

— Webster v. Blue Ship Tea Room, Inc., 198 N.E.2d 309, 312 (Mass. 1964). Thanks to Daniel Green.

November 26th, 2011  Dangerous product? A large guy (280-90 pounds) ironically won a one-week trip to Hawaii as a reward for selling more than $20,000 in diet products. But in a lawsuit against Hanes, the underwear maker, he alleged his “dream trip” went awry due to allegedly defective briefs which “gaped open and acted like a sand belt on my privates,” causing injury.

We’ll let the court elaborate on this interesting products liability case:

Plaintiff testified that by the second day in Hawaii he was in debilitating pain. However, … he ignored the pain until he returned to Pensacola two weeks later. He explained he was able to ignore the pain because he was enjoying himself so much on this long anticipated vacation that he did not dwell on or focus on the pain to any degree.

Plaintiff testified he believed sand that he picked up in his swim trunks while enjoying the Hawaiian surf had irritated his penis. Over the next few days he and his wife “walked all over the place” until his condition worsened to the point that he “could hardly walk.” Plaintiff testified his inability to walk was caused by defendant’s defective manufacturing of his underwear which caused his “fly” to gap open. The gap resulted in his penis protruding from his underwear, whereupon the edges of the opening abraded his penis like “sandpaper belts.” …

Under cross examination plaintiff admitted he never examined his penis to assess the problem and/or treat the problem. He testified he is a “belly-man” and his “weight” prevents him from looking down and seeing his penis. He further testified he declined to use the hotel mirror to view the “injury” because that is “not something he would do.” He also testified he did not ask his wife to examine his penis because he would never ask her to do such a thing, nor would he want to let her know about his pain because it would have “ruined her vacation” as well. …

So how does one prove a complex products liability case like this one? How else? Bring on the experts! Nothing like an in-court reenactment to drive home a point (will resist the obvious “if they do not fit, you must acquit” joke):

Both the plaintiff and the defendant’s expert demonstrated the “tensions” that are placed on men’s underwear. This was done by holding the allegedly “defective” underwear and placing it under various “stresses” while comparing it with similar briefs made by other manufacturers, as well as other old, worn out Hanes brand briefs owned by plaintiff.

The uncontroverted expert testimony was that once a man’s genitalia are adjusted in his briefs, “vertical tension” is far greater than horizontal tension and there is no tendency for the fly to “gap.”

Based on the expert testimony, the judge concluded that “it was clear to the court that plaintiff’s underwear would not have ‘gaped’ open as contended by plaintiff because the tension load on men’s underwear is vertical and not horizontal.” The court speculated that it was more likely that plaintiff’s problems were caused by the “plaintiff’s manner of getting into his underwear,” which was to put them on at the same time as his pants.

The surprising legal lesson of this case is that expert testimony about tighty-whities fit can apparently pass scrutiny as scientifically valid under Daubert.

— Freed v. Hanes Brands, Inc., Case No. 2009 SC 003087 (Fla. Escambia County Ct. Oct. 12, 2009). Thanks to Cecile Mendizabel and others.

November 26th, 2011 Thanks to Oregon Circuit Judge G. Philip Arnold for sending us Franklin v. Oregon. The opinion details the plight of Oregon federal district Judge James M. Burns and a unique prison inmate named Harry Franklin back in 1983. Their longterm relationship was on the rocks when Burns penned these opening words:

This is another chapter in the Harry Franklin saga. No longer am I tempted to call it the final chapter, as desirable as that would be to me. I mention mournfully that only the finality of death—his or mine—would enable the other of us to use the term “final” in that way. And, of course, if mine comes first, I have no doubt that another judge will someday express lamentations such as these.

Franklin was a prolific inmate litigator. Burns had already dismissed 37 cases he filed, only to receive two dozen more. These were on top of 45 other lawsuits filed by the inmate, which were dealt with by a different judge.

Here are some of the claims Judge Burns had to contend with:

– A claim for $3 million damages for mental frustration suffered by Franklin when a Portland television station allegedly misidentified a “14 wheeler tractor and trailer rig” as an “18 wheeler.”

– A claim for “Harassment by Water” arising from the Oregon State Prison’s sprinkling of the prison yard during summer months, which prevented Franklin from finding a dry place to lie down.

– A claim that the Oregon State Prison wrongfully bakes its desserts in aluminum rather than stainless steel pans.

How did the inmate decide which of his claims had merit? In his words:

FN1. “The Lord spoke to me, and he told me to file these lawsuits and said, ‘You will win big in your lawsuits,’” the heavy-set, white haired convict said. “He showed me an enormous elephant. He said that the elephant represents the big, gray courts, which is the government. Anyway, I was leading this elephant through every section of this penitentiary,” he said. “I was writing on a yellow legal pad. Each place we came to I’d jot something down and slap the sheet onto the elephant. And they all stuck. The Lord told me the sheets were suits. I never could get over that monstrous elephant.”

— Franklin v. Oregon, 563 F. Supp. 1310, 1316–17 & n.1 (D. Or. 1983). Thanks, Judge.

November 24th, 2011  A $600,000 jury verdict for losing psychic powers sounds ridiculous, and likely the grossly misunderstood McDonald’s coffee spill case, Haimes v. Temple University has been abused as a tool to whip up on trial lawyers and the tort system. But as with the McDonald’s case, Haimes got twisted in the telling. A $600,000 jury verdict for losing psychic powers sounds ridiculous, and likely the grossly misunderstood McDonald’s coffee spill case, Haimes v. Temple University has been abused as a tool to whip up on trial lawyers and the tort system. But as with the McDonald’s case, Haimes got twisted in the telling.

Plaintiff Judith Richardson Haimes brought a medical malpractice action against defendant after a CT scan allegedly caused her chronic and disabling headaches and prevented her from practicing her occupation as a psychic. A jury awarded her $600,000 after a four-day trial.

Wow! But pro-tort reform accounts of the case omit two critical facts. First, that the trial judge specifically instructed the jury it could NOT award damages for loss of her psychic abilities, and, second, that the court threw out the plaintiff’s verdict.

Having cleared that up, the most interesting part of the case was the testimony pertaining to her psychic abilities. The plaintiff presented several police officers as witnesses who testified that plaintiffs’ psychic abilities had helped them solve cases. One special agent testified that he sought plaintiff’s advice in solving five to seven homicide cases and that information provided by plaintiff proved to be 80-90 percent accurate. The opinion describes detailed information plaintiff provided to help solve a variety of cases. It’s interesting.

— Haimes v. Temple University Hosp., 39 Pa. D. & C.3d 381 (Pa. Ct. Com. Pl. 1986). Thanks to Cynthia Cohan.

November 24th, 2011 According to North Carolina Judge David K. Fox, General Court of Justice, Transylvania County, “Teenaged boys were created to mumble darkly whilst doing yard work to justify their existence on earth and their room and board.”

That’s just one of many pearls offered by Judge Fox in a temporary support order in a divorce case, an order as hilarious as it is skillfully articulated.

The facts are extensive, but basically, the husband, a doctor, was seeking relief from support payments to his ex-wife, who, along with her kids, was living quite well on the ex-hubby’s income while declining to seek substantial work of her own.

The wife had been a nurse, a fact not surprising to Judge Fox, who commented “[t]hat, as predictable as death and taxes, doctors marry nurses for second and subsequent unions.”

Neither the wife nor husband, according to Judge Fox, had managed to adjust their respective lifestyles in light of the doc’s substantially declining income attributable to shifts in the healthcare industry. The result, said Judge Fox, was “an ongoing mathematical economic train wreck.”

Part of the problem was that, “since separation, the Parties have undertaken to continue their relationship based upon the constitution and bylaws of the Jerry Springer Show.” The wife’s grown kids from a prior marriage weren’t helping matters either, causing Judge Fox to remark that “[i]t is a mercy that [the husband’s] children by his prior marriage are in Illinois.”

The comment about teenage boys came in response to the fact that the wife was forking out $250 a month for yard work instead of making her healthy 17-year-old son get off his duff and push a lawnmower.

While Judge Fox’s sympathies seemed to lie with the husband, the doc didn’t escape unscathed. Judge Fox described him as “rotund” and “a vessel of ill health, both actual and potential.”

But good news! The husband had “acquired a reciprocal, apparently romantic, interest in a local female (working in the health-delivery industry, of course),” causing the judge to speculate “that this relationship likely is the primary reason he has begun to address his weight problem with some increase in beneficial exercise, including the muscular effort of pushing aside the dinner plate more frequently.”

The judge granted the husband support relief and everyone else comic relief. This summary doesn’t do justice to Judge Fox’s order. The overall tone, while definitely somewhat sarcastic, is not mean-spirited. He seemed genuinely concerned about the parties’ well-being, but also frustrated by their apparent inability to grasp their economic straits.

— Order in Temporary Support, Bodie v. Bodie, Case No. 08-VVD-334 (N.C. Dist. Ct., July 11, 2006). Thanks to Andrew J. Dolson.

November 24th, 2011 Sometimes you just need to know when to fold ‘em.

In a 1963 divorce case, the wife accused the husband–a dentist–of adultery with several of his patients. The husband vigorously contested the allegations. Fifteen hundred pages of testimony later, the case made it to the New Jersey Superior Court, which had to decide whether the evidence proved adultery.

The husband had creative explanations for every bit of damning evidence. For example, when the wife produced a film she found of the husband inserting a speculum into a nude patient in his office, he said he was conducting medical research. Remember, he’s a dentist.

On another charge, the wife claimed she came into the husband’s office one day to find him having sex on his dental couch with a nude patient identified in the case as “Mrs. G.” The husband denied having sex with Mrs. G. He said he was merely carrying her to the couch because of her sudden loss of consciousness while he was removing a denture. (No explanation as to why she was nude.)

He maintained his denial even in the face of a diary entry he made on the same date with reference to Mrs. G that said “[C]aught!” He explained that this was actually a medical entry meaning that the denture “caught” in Mrs. G’s mouth tissue while he was removing it.

The opinion is jammed with other elaborate, laughable denials that make for some interesting reading.

— Lowenstein v. Lowenstein, 190 A.2d 882 (N.J. Super. Ct. 1963). Thanks to Seymour Margulies.

November 24th, 2011

Prosecutor used Celine Dion's and Enya's music to soften up jury. Salazar v. Texas was a grisly murder case involving a victim and alleged dope dealer named Jonathon. Jonathon’s cohorts turned on him and killed him by beating him with baseball bats and strangling him with wire.

At the punishment phase of the trial, over the objection of defense counsel, the state played a professionally edited video montage of Jonathon’s life, complete with music by Enya and Celine Dion!

The defendant appealed on the ground that the videotape was prejudicial. Here’s how the appellate court described the videotape (paragraph breaks inserted):

This video is an extraordinarily moving tribute to Jonathon Bishop’s life. It consists of approximately 140 still photographs, arranged in a chronological montage. Music accompanies the entire seventeen-minute video and includes such selections as “Storms in Africa” and “River” by Enya, and concludes with Celine Dion singing, “My Heart Will Go On,” from the movie Titanic.

Almost half of the approximately 140 photographs depict the victim’s infancy and early childhood. The pictures show an angelic baby, surrounded by loving parents, grandparents, unidentified relatives, and other small children. Later photographs show Jonathon as a toddler, playing the piano, frolicking at the beach with other friends, happily riding on a carousel, laughing in a field of bluebonnets, and cuddling with a puppy.

The video also includes numerous annual school pictures showing Jonathon’s progression from a cheerful child to a equally cheerful young man. It catalogs his evident and early prowess as a young soccer player and eventually as a football player. There is a picture of him and his date, presumably going to their prom, and more candid shots of the victim and his teen-age buddies. The video includes many family reunion portraits showing Jonathon’s entire extended family.

Understandably, this professional and polished production portrays Jonathon in a very positive light and it is entirely appropriate for a memorial service. The music, too, is appropriately keyed to the various visuals, sometimes soft and soothing, then swelling to a crescendo chorus. In sum, it is a masterful portrait of a baby becoming a young man. It is also extraordinarily emotional.

The court held it was reversible error to admit the videtape into evidence on the ground that its relevance was outweighed by its prejudicial value, stating:

[The] prejudicial effect is enormous because the implicit suggestion is that the appellant murdered this angelic infant; he killed this laughing, light-hearted child; he snuffed out the life of the first-grade soccer player and of the young boy hugging his blond puppy dog.

— Salazar v. State, 90 S.W.3d 330, 333–34, 337 (Tex. Crim. App. 2002). Thanks to Texas Senior Judge James Barlow.

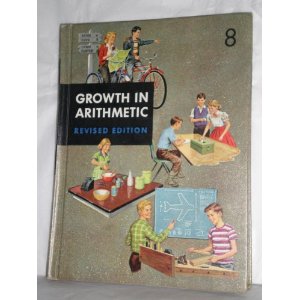

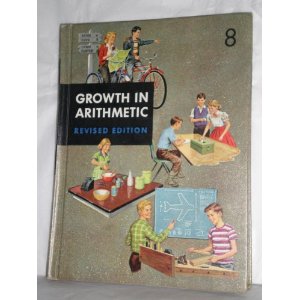

November 24th, 2011  Eighth-grade math book held to be controlling authority by a federal appellate court. You gotta love an opinion that begins:

In this appeal we are asked to determine whether “.82″ is the equivalent of “82%.” Having successfully completed grammar school, we are able to answer the question in the affirmative.

An unsuccessful bidder for an offshore oil and gas lease brought suit against the Secretary of the Interior for awarding the contract to a competitor. The plaintiff offered a royalty of “73.45689%” in its bid. A competitor offered a royalty bid of “.82165.” The Secretary construed the competitor’s bid as one for 82.165 percent, and awarded the contract to it based on it being the higher bid.

The plaintiff asserted the Secretary acted arbitrarily and capriciously in construing .82165 to be 82.165 percent. The trial court agreed and entered judgment for the plaintiff.

The U.S. Court of Appearls for the Fifth Circuit reversed, relying on as its primary source of authority an eighth-grade math book called “Growth in Arithmetic,” which the Court said asked and answered the pertinent question: “Do you know how to change a per cent to a decimal?”

— Oil & Gas Futures, Inc. of Tex. v. Andrus, 610 F.2d 287, 287–88 (5th Cir. 1980). Thanks to Frank Zotter.

November 24th, 2011 Ohio Court of Appeals Judge Mark Painter combined humor and common sense in Gibson v. Donahue, where the plaintiff was injured being thrown from her horse, which was spooked by two Irish Setters that the defendant allowed to run free in an area restricted to equestrian use.

Talk about creative lawyering. The defendant tried to escape liability by relying on an Ohio statute intended to provide tort immunity for riding stable owners and horse show operators for injuries resulting from the inherent risks of equine activity (a statute Painter said “is noteworthy mainly for using the word ‘farrier’ ten times”).

Judge Painter observed that the case was one of first impression, “probably because no one before has been audacious enough” to try to extend the statute to a situation like this one.

Defendant did have a slim statutory leg to stand on. The statute extends immunity to “an equine activity sponsor, equine activity participant, equine professional, veterinarian, farrier, or other person.” However, Judge Painter said that for defendant’s construction to prevail, the statute would have to be read as applying to “any other person in the whole world.” Construed as defendant argued, “[a] person who negligently crashes an airplane into the crowd at an equine event would thus be immune to liability.”

By the way, a farrier is a blacksmith. Remember that if you’re a law student in Ohio. It might be on the bar exam.

— Gibson v. Donahue, 772 N.E. 2d 646, 648, 650 (Ohio Ct. App. 2002).

November 24th, 2011  Ohio Court of Appeals Judge Mark Painter writes some amusing opinions. He had a bit more leeway to let loose back when he was a municipal judge presented with some highly unusual fact patterns. Ohio Court of Appeals Judge Mark Painter writes some amusing opinions. He had a bit more leeway to let loose back when he was a municipal judge presented with some highly unusual fact patterns.

In State v. Kirchner, the defendant was charged with aggravated menacing and resisting arrest. It all started just because he wanted to hang out one night at home with some friends–with a five-foot dead snake nailed to his door. Read on and enjoy:

The evidence adduced presented, at the very least, a bizarre situation. Cincinnati Police Officers Randy Froehlich and Steve Means received a radio dispatch to an address … in the “Over-the-Rhine” section of Cincinnati. The reason for the dispatch was “man nailing snake to door.”

Upon the officers’ arrival … they did in fact discover a five-foot-long black snake which had been nailed through its head to the door of defendant’s apartment. Though the record is silent on the point, assumedly the snake was deceased.

Quite naturally, the officers knocked on defendant’s door, which defendant answered, and sought to question defendant concerning the snake. The officers asked if they could come in and talk with the defendant, to which he replied, “no.” The entire situation deteriorated from that point forward, resulting in the events in this court.

Quite obviously, the defendant had a right, under the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution, to refuse to allow the officers to enter absent a warrant or perhaps exigent circumstances, which did not exist in this case. Of course, a prudent man would have talked with the officers to resolve the situation, but the Constitution applies to both prudent and imprudent men.

Defendant testified that the snake was not his, he had not nailed it to the door, and since it was not his snake, he did not believe it to be his responsibility to remove it. Defendant believed that the caretaker of the apartment building would eventually remove the snake, which had been hanging for approximately eight hours. Defendant did not wish to converse with any police officer, because he and his friends were engaged in a social visit, involving the use of Wild Irish Rose wine.

[A struggle ensued when the defendant stepped back and put his hands on his hips. A folding knife in a sheath was on his belt. The officers interpreted his movement as “going for” the knife. They drew their weapons, disarmed and arrested the defendant.]

The question remains as to what, if any, laws the defendant had violated. It might be noted that no charges were filed against anyone in connection with the mistreatment of the snake. Under Cincinnati Municipal Code Section 701-11, “[n]o person shall … cruelly beat, mutilate … any animal …..” An “animal” is defined … as follows: “‘[a]nimal’ shall, for the purposes of Sections 720-11 and 720-13, mean and include every living dumb creature.” The above definition would obviously include a snake, though the inartful wording might imply that it would be perfectly legitimate to torture a talking parrot. Be that as it may, since the defendant denied nailing the snake to the door, the officers were evidently not able to determine the identity of the nailor, the nailee obviously being unable to testify.

We do not find that defendant’s actions … constitute the crime of aggravated menacing. Perhaps the entire matter could be classified under “aggravated foolishness,” though there is no section in the Revised Code proscribing such conduct. If there were, our jails would be a great deal more crowded than they are presently.

Judge Painter found sufficient evidence to support a conviction of the defendant for resisting arrest.

— State v. Kirchner, 483 N.E.2d 497, 498–99 (Ohio Mun. 1984).

November 21st, 2011 Nothing funny about U.S. v. Pipkins, a case involving RICO convictions for several “pimps,” including convictions for using underage woman as prostitutes. But it certainly qualifies as “strange,” given the Eleventh Circuit’s elaborate explanation of the complex hierarchy and jargon of pimping and prostitution, which in this case even included instructional videos for both pimps and prostitutes. Here are some excerpts:

[E]ach pimp kept a stable of prostitutes with a well-defined pecking order. At the top of each pimp’s organization was his “bottom girl,” a trusted and experienced prostitute or female associate. Next in the pimp’s chain of command was a “wife-in-law,” a prostitute with supervisory duties similar to those of the bottom girl. A pimp’s bottom girl or wife-in-law often worked the track in his stead, running interference for and collecting money from the pimp’s other prostitutes. The bottom girl also looked after the pimp’s affairs if the pimp was out of town, incarcerated, or otherwise unavailable.

The pimps also recognized a hierarchy among their own. “Popcorn pimps,” “wanna-bes,” and “hustlers” were the least respected, newer pimps. A “guerilla pimp” (as other pimps and prostitutes considered Moore) primarily used violence and intimidation to control his prostitutes. Others were regarded as “finesse pimps,” who excelled in the psychological trickery needed to deceive juvenile females and to retain their services. Finally, “players” (apparently, in this case, Pipkins) were successful, established pimps who were well-respected within the pimp brotherhood. …

The pimping subculture in Atlanta operated under a set of rules, presented in the video called Really Really Pimpin’ in Da South. This videotape was made in Atlanta by Pipkins and Carlos Glover, a business associate. Really Really Pimpin’ in Da South featured prominent Atlanta pimps, including Pipkins, explaining the rules of the game. This video, along with its companion piece, Pimps Up Hoes Down, outlined the pimp code of conduct, and was repeatedly shown to new pimps and prostitutes alike to concisely explain what was expected of a prostitute. The origin of Pimps Up Hoes Down is unknown. In essence, these videos taught that prostitutes were required to perform sexual acts, known as “tricks” or “dates,” for money. … Despite the pimps best efforts to subjugate their prostitutes, the rules allowed a prostitute to move from one pimp to another by “choosing.” This was accomplished by the prostitute making her intentions known to the new pimp, and then presenting the new pimp with money, a practice known as “breaking bread.” The new pimp would then “serve” the former pimp by notifying him that the prostitute had entered his fold. The former pimp was bound to honor the prostitute’s decision to choose her new pimp. A prostitute who frequently moved from pimp to pimp was known as a “Choosey Susie.” And, a prostitute might “bounce” from pimp to pimp by moving among different pimps without paying for the privilege of choosing.”

The court also detailed extensive physical abuse against prostitutes as part of the “rules govern[ing] a prostitute’s conduct,” mentioned that one defendant used his prostitutes to “entertain[ ] members of a municipal police force at his home,” and noted that the pimps “operated as a price-fixing cartel” to regulate prices for prostitution services.

If you ever thought prostitution was a “victimless crime,” go read this opinion.

— United States v. Pipkins, 378 F.3d 1281, 1285–86 (11th Cir. 2004). Thanks to Paul Scott.

November 18th, 2011  Family friendly depiction of the injury. Doe v. Moe, a May 2005 Massachusetts appellate case, gives a whole new meaning to the idea of safe sex. A guy sued his long-time girlfriend (ex-girlfriend?) for negligence when an ill-advised change in position during consensual intercourse resulted in him suffering a fractured penis. (The opinion gives details about how the accident occurred.)

In a case of first impression, the court struggled to arrive at an appropriate and workable standard of care to apply to private consensual sexual conduct. The court noted:

There are no comprehensive legal rules to regulate consensual sexual behavior, and there are not commonly accepted customs or values that determine parameters for the intensely private and widely diverse forms of such behavior.

Accordingly, the court concluded that the general negligence standard of reasonable care under the circumstances was inappropriate for consensual sex-physical injury cases.

Instead, the court said the plaintiff needed to show conduct rising to the level of “wanton or reckless.” The court opined that while the trial record might support a finding that the defendant’s conduct exposed plaintiff to a risk of harm, it did not support a finding of wanton or reckless conduct.

The case does raise an interesting legal issue. With so many different preferences and positions and idiosyncratic fantasies and fetishes, is there such a thing as a standard of “ordinary and reasonable care” for sex?

— Doe v. Moe, 827 N.E.2d 240, 245 (Mass. Ct. App. 2005). Thanks to David Keller and Professor Howard Wasserman.

November 17th, 2011  Changing venue because of a volcano? Sure, it sounds far-fetched, but don’t blow your stack. Changing venue because of a volcano? Sure, it sounds far-fetched, but don’t blow your stack.

It really happened in U.S. v. McDonald, a 1990 federal bribery prosecution in Alaska. Fearful that an unpredictable volcano named Mt. Redoubt would act up and disrupt the trial, Judge James M. Burns granted a motion to change venue for the trial from Fairbanks, Alaska to Tacoma, Washington.

Judge Burns noted he could find “no precedent for changing venue because of an earthquake, hurricane, tornado, flood, volcanic eruption, or other natural disaster,” but said Mt. Redoubt was “entitled to a modicum of judicial respect.”

Judge Burns might be a Jimmy Buffett fan. Usually, when you think of Buffett, you think frozen margaritas, not frozen tundra, but footnote 17 quotes the entire lyrics of the Jimmy Buffett song “Volcano,” observing that Buffett’s lyrics express feelings apropos to the circumstances of the case.

Buffett sang, “I don’t know, I don’t know where I’m a-gonna go when the volcano blow.”

Here they knew. The judge sent everyone to Tacoma.

— United States v. McDonald, 740 F. Supp. 757, 764 nn.17 & 18 (D. Alaska 1990) (Burns, J.). Thanks to Tom Gaylord.

November 16th, 2011  Won a defamation judgment for being called ugly. A 1996 English libel case reminds me of the old Rodney Dangerfield joke: “My psychiatrist told me I’m going crazy. I told him, ‘Doc, if you don’t mind I’d like a second opinion.’ He said, ‘Alright, you’re ugly too.’”

In Berkoff v. Burchill, an English court of appeals held that describing a person as ugly can constitute actionable defamation. No wonder people are flocking to England to take advantage of the country’s plaintiff-friendly libel laws. It’s highly doubtful calling someone ugly would be actionable defamation under U.S. law.

(By the way, this practice, known as “libel tourism,” resulted in enactment of a 2010 U.S. law that prohibits U.S. courts from enforcing foreign defamation judgments if they were rendered under legal protections less protective of speech than U.S. standards. Berkoff’s suit, against an English newspaper, was not a case of libel tourism.)

The English case arose from a Sunday Times article in which defendant Burchill reviewed the movie The Age of Innocence. Burchill described the film director, Steven Berkoff, as “hideous-looking.”

Nine months later, Burchill once again called Berkoff’s pulchritude into question, this time in a review of the movie Frankenstein. Describing “the Creature,” Burchill said: “It’s a very new look for the Creature—no bolts in the neck or flat-tap hairdo—and I think it works; it’s a lot like Stephen Berkoff, only marginally better-looking.”

Berkoff sued for defamation. The issue was whether calling someone hideous-looking is a defamatory statement capable of injuring a person’s reputation. The appellate court answered affirmatively.

The court said a jury could “conclude that in the context the remarks about Mr. Berkoff gave the impression that he was not merely physically unattractive but actually repulsive” and that this could injure Berkoff’s ability to make a living by “lowering his standing in the estimation of the public … [by] making him an object of ridicule.”

Is truth a defense? He looks okay in this picture (photo by Getty, borrowed from The Telegraph).

— Berkoff v. Burchill, [1996] 4 All E.R. 1008 (Ct. App. 1996). Thanks to Heiner O. Mommsen.

November 14th, 2011 In a classic slip and fall case, plaintiff Joseph Rosenberg slipped on asparagus while dancing at a wedding reception with his sister-in-law and fellow plaintiff, Ruth Schwartz.

The issue was whether the defendant caterer had negligently spilled the asparagus on the dance floor. The trial judge had dismissed the lawsuit on theory that the offending asparagus could have been unwittingly transported onto the dance floor after becoming entrapped in the apparel of the dancers.

As with many of the judicial opinions posted on Lawhaha.com, brief excerpts don’t do this case justice. My favorite part is how the legendary Justice Michael Angelo Musmanno of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court bluntly and rather contemptuously rejected the trial judge’s theory of how the asparagus (which according to testimony formed a puddle three feet in diameter) got on the dance floor (some paragraph breaks inserted):

The trial judge, an ex-veteran congressman and thus a habitue of formal parties and accordingly an expert in proper wearing apparel at such functions, all of which he announced from the bench, allowed testimony as to the raiment worn by the banquetters.

All the men were attired in tuxedos, the pants of which were not mounted with cuffs which could transport asparagus and sauce to the dance floor, unwittingly to lubricate its polished surface. Ruling out the cuffs of the tuxedo pants as transporters of the asparagus, the judge suggested the asparagus, with its accompanying sauce, could have been conveyed to the dance floor by ‘women’s apparel, on men’s coats or sleeves, or by a guest as he table hopped.’

The Judge’s conclusions are as far-fetched as going to Holland for hollandaise sauce. There was no evidence in the case that anybody table hopped; it is absurd to assume that a man’s coat or sleeve could scoop up enough asparagus and sauce to inundate a dance floor to the extent of a three-foot circumference; and it is bizarre to conjecture that a woman’s dress without pockets and without excessive material could latch on to such a quantity of asparagus, carry it 20 feet (the distance from the tables to the dance floor) and still have enough dangling to her habiliments to cover the floor to such a depth as to fell a 185 pound gentleman with 35 years’ dancing experience who had never before been tackled or grounded while shuffling the light fantastic.

…

It can be stated as an incontrovertible legal proposition that anyone attending a dinner dance has the inalienable right to expect that, if asparagus is to be served, it will be served on the dinner table and not on the dance floor.

…

Judgment reversed with a procedendo.

Chief Justice Bell dissented:

One cannot help wondering if plaintiffs had, in the alleged 35 years of dancing, ever been to any dance, let alone a wedding banquet dance. … A dancer cannot, with legal sanction, look only into the captivating eyes of his lovely partner.

I certainly dissent.

— Schwartz v. Warwick-Philadelphia Corp., 226 A.2d 484, 485–87, 488 (Pa. 1967). Thanks to Janet Heydt.

November 14th, 2011  The Kinks got it right in their song, “Destroyer,” when they sang that paranoia will destroy ya. The Kinks got it right in their song, “Destroyer,” when they sang that paranoia will destroy ya.

It certainly did so for the defendant in a case where, after getting paranoid at a 1999 Phish concert in Oswega, NY, presumably while under the influence of an hallucinogenic drug, he became convinced the police were following him and that the band was sending him messages through the music. Fleeing the concert, he traveled 250 miles on foot and by hitch-hiking, convinced the police were after him the whole way. (He believed that every car with an “A” in the license number contained police officers.)

Some thirty-six hours later, he finally turned up at the police barracks in Westport, NY, where he told an investigator, “You know who I am.” When the cops didn’t know who he was or why he was there, he told them he was growing marijuana plants back at his home in Rochester, NH. He then consented to a search of the house.

When the cops in Rochester searched the house, they found marijuana plants and liquid acid. Though a New Hampshire Superior Court ultimately ruled that the evidence should be suppressed (because of insufficient proof the defendant received and waived his Miranda rights), the University of Memphis law student who sent me this opinion correctly opined that it should serve as “a gentle reminder to any students planning to reunite with Phish over the summer break.”

— State v. Augur, Case Nos. 01-S-388, 01-S-389, 2001 N.H. Super. LEXIS 17 (N.H. Super. Ct., Oct. 22, 2001). Thanks to Adam Ragan.

November 13th, 2011

All the horsepower without the sharp teeth or drunk-driving convictions. Things weren’t looking good for the defendant in State v. Stagno after getting pulled over by a state trooper. With a blood alcohol level of .197 and two DUI convictions in the past ten years, he almost certainly would’ve lost his driver’s license if he’d been driving his friends to the topless bar in his car.

But thanks to a drunken bet made earlier in the evening, the defendant’s mode of transportation on this wild night out was not a car at all—it was a “fifteen-foot 1985 Air Gator airboat, powered by a 455 cubic inch Buick engine.”

Because the applicable statute allowed judges to revoke driver’s licenses only when the vehicle driven required a license, the trial court had to settle for imposing a $1,000 fine, thirty days in jail, and alcohol rehabilitation counseling.

The Alaska Court of Appeals affirmed the lower court’s ruling, agreeing that a fifteen-foot airboat is not a motor vehicle requiring a driver’s license.

— State v. Stagno, 739 P.2d 198 (Alaska Ct. App. 1987)

November 10th, 2011 A dispute over the quality of a breakfast sausage at a Denny’s restaurant adds to the burgeoning inventory of rhyming judicial opinions. The ridiculous disagreement that gave rise to the case is more amusing than the prose.Dissatisfied with the quality of some breakfast sausage, the appellant and his companion sent the sausage back to the kitchen. When the bill arrived, appellant demanded that it be reduced by the ala carte price for the sausage ($3.20), but the Denny’s assistant manager, obviously destined for full manager status, agreed to deduct only $1.20.

Appellant balked, left four bucks and departed, and thus arose the Great Two-Dollar Theft Case. Denny’s had the appellant arrested for theft. After the charge was dismissed, appellant filed a civil action for malicious prosecution, which also was dismissed.

On appeal, Judge Cercone of the Pennsylvania Superior Court, in obvious frustration over having to expend scarce judicial resources over two bucks, was moved to wax poetic:

Sausage and eggs!

Sausage and eggs!

$2.02 he refused to pay

So now in court it’s for us to say.

Sausage and eggs!

It wasn’t the price

The parties contend

It’s the principle, they pretend.

Sausage and eggs! $2.02 involved.

A sum so easily resolved

But no give or take here

They insist on a legal atmosphere.

Oh, in Uncle Sam’s land

Any person in court may protest

But, dear Lord, the Judge says

From this test, please give me rest.

He concluded his opinion with the statement: “Preserve us from more of this!” We concur. Maybe judges should be required to attend poetry writing classes before being sworn in.

— Amicone v. Shoaf, 620 A.2d 1222, 1223 (Pa. Super. Ct. 1993). Thanks to Melanie Ware.

November 7th, 2011  Maybe he really is Santa Claus. Warren J. Hays continued to brew trouble with that official Ohio identification card issued to him in the name of Santa Claus, listing his address as 1 Noel Drive, showing his birth date as December 25, 1900, and bearing a picture of him in a false beard.

“Santa Claus Is Coming to Court” recalls part one of the drama.

After being involved in a minor accident in his car, “which resembled a sleigh,” Hays presented his Santa Claus ID to the other party, who showed it to a police officer-friend of hers. The officer, suspecting that Hays might not really be Santa Claus, met with the prosecutor, who filed a misdemeanor complaint against Hays alleging that he provided false information in obtaining an the Ohio ID card.

The instant action was Hays’ suit for malicious prosecution and abuse of process, which he lost.

The burning question remains: How does a man claiming to be Santa Claus obtain an official state ID card? On the other hand, maybe he really is Santa Claus, in which case the state should quit hassling him so he can get ready for the holidays.

— Hays v. Merkel, Case No. 2003-T-0082, 2004 Ohio App. LEXIS 4476 (Ohio Ct. App. 2004). Thanks to Matt Vansuch.

November 7th, 2011  "Am looking for a good lawyer. Can pay in acorns. Hit me up." Appellate Judge Joseph Hudock of the Superior Court of Pennsylania treated us to a classic in a case involving a poor little persecuted squirrel named Nutkin.

For an alleged questionable motive (explained in the opinion), the state decided to prosecute Nutkin’s owner for keeping the squirrel as a family pet in violation of Pennsylvania wildlife laws. The good news is that Nutkin and the owner won. The better news is Judge Hudock’s opinion. This one is worth reading in full. Here are the opening paragraphs to give you a taste:

1. This appeal revolves around the life and times of Nutkin the squirrel.

2. Nutkin’s early life was spent in the state of nature ferrae naturae, in the state of South Carolina, and, as far as we can tell, in a state of contentment. She apparently had plenty of nuts to eat and trees to climb, and her male friends, while not particularly handsome, did have nice personalities. Life was good.

3. Then one day tragedy struck: Nutkin fell from her tree nest!

4. But fate was kind. Nutkin was found and adopted by Appellant and her husband who, at that time, were residents of South Carolina. Appellant lovingly nursed Nutkin back to health, and Nutkin became the family pet. . . . Life was good again.

5. Nutkin’s captivity and domestication were perfectly legal in South Carolina, possibly a reflection of that state’s long tradition of hospitality to all.

6. In 1994, Appellant and her husband moved to Pennsylvania and brought Nutkin with them. Life was full of promise.

7. Dark clouds began to gather, however … [when the mean old state of Pennsylvania came into the picture and tried to take Nutkin away].

. . .

9. Nutkin would then learn the shocking truth that the cheery Pennsylvania slogan “You’ve got a friend in Pennsylvania” did not apply to four-legged critters like Nutkin.

If you track down the full opinion, keep an eye out for the funny analogy Judge Hudock draws between old squirrels and old appellate judges.

— Commonwealth v. Gosselin, 861 A.2d 996, 997–98 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2004). Thanks to Ryan Kriger.

November 6th, 2011  A man named Warren J. Hayes somehow was able to obtain an official Ohio Identification Card in the name of “Santa Claus.” He also managed to get an official motor vehicle registration, AAA membership card, and checking account in Santa’s name, all of them listing his address as 1 Noel Drive, North Pole USA. A man named Warren J. Hayes somehow was able to obtain an official Ohio Identification Card in the name of “Santa Claus.” He also managed to get an official motor vehicle registration, AAA membership card, and checking account in Santa’s name, all of them listing his address as 1 Noel Drive, North Pole USA.

Hayes/Claus ran into trouble when he was involved in a minor car accident and produced his Santa Claus ID to a cop. He was charged under an Ohio statute prohibiting the use of “fictitious” names.

Perhaps in the Christmas spirit (although the case was decided in the heat of summer), Ohio Judge Thomas P. Gysegem let Mr. Hayes/Claus off the hook with this reasoning:

[T]he court’s dilemma is whether Santa’s act of displaying this identification card under these circumstances and with this history (noted above) violated the law, to wit, Was this identification card “fictitious”?

Webster’s Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary defines “fictitious.” Its analysis of the word includes a synonym comparison with “fabulous,” “legendary,” “mythical,” and “apocryphal”:

“Fabulous stresses the marvelous or incredible character of something without distinctly implying impossibility or actual nonexistence; Legendary suggests the elaboration of invented details and distortion of historical facts produced by popular tradition; Mythical implies a purely fanciful explanation of facts or the creation of beings and events out of the imagination; Apocryphal implies an unknown or dubious source or origin for an account circulated as true or genuine. … Fictitious implies fabrication and suggests artificiality or contrivance more than deliberate falsification or deception.”

Had Santa been charged with being “fabulous, legendary, mythical or apocryphal,” he might well indeed be guilty facing up to 180 days in jail and a $1,000 fine. However, to sustain the burden of going forward, the state must make a showing that Santa knowingly displayed an identification card that was “fictitious.” This the state has not done. The fact that Santa had an ongoing relationship for 20 years with the BMV is not indicative of “artificiality or contrivance,” for, in fact, under the publicly held records of the Ohio Bureau of Motor Vehicles, Santa has been a “real person” since as early as 1982.

Never explained in the opinion is how the Ohio Bureau of Motor Vehicles allowed a person to obtain and renew official documents in the name of Santa Claus for twenty years.

— State v. Hayes, 774 N.E.2d 807, 810 (Ohio Mun. Ct. 2002). Thanks to Mardee Sherman.

November 6th, 2011  An alleged alien from outer space—a Martian, to be precise—was outsmarted by good old terrestial law. An alleged alien from outer space—a Martian, to be precise—was outsmarted by good old terrestial law.

The plaintiff claimed to be a Martian. He filed three lawsuits in Canada against numerous defendants, including the CIA and then-President Bill Clinton, alleging the defendants had taken various steps that interfered with his ability to live freely as a Martian. He asserted the only reason he could not prove his Martian status was because the CIA tinkered with his DNA test. (This is actually starting to sound like a good action movie plot …)

Ironically, and perhaps unfairly, the essence of the plaintiff’s claim did him in. Judge Epstein explained:

Rule 1.03 defines plaintiff as “a person who commences an action”. The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary defines person as “an individual human being”. Section 29 of the Interpretation Act provides that a person includes a corporation. It follows that if the plaintiff is not a person in that he is neither a human being nor a corporation, he cannot be a plaintiff as contemplated by the Rules of Civil Procedure. The entire basis of Mr. Joly’s actions is that he is a martian, not a human being. There is certainly no suggestion that he is a corporation. I conclude therefore, that Mr. Joly, on his pleading as drafted, has no status before the Court.

Judge Epstein also found the claims to be frivolous, vexatious and “patently ridiculous.” However, the court did not find plaintiff to be mentally incompetent. To the contrary, Judge Epstein wrote that Joly “presented himself as polite, articulate, intelligent and appeared to understand completely the issues before the Court and the consequences should I grant the relief sought.”

— Joly v. Pelletier, [1999] O.J. No. 1728 (Ont. Super. Ct. 1999). Thanks to David Cheifetz, one of the lawyers involved in this interesting case.

November 6th, 2011 The lawyer who sent in this opinion wrote that it will “make you pee in your pants laughing.” Maybe he was just caught up in the spirit of the opinion, which begins:

This case decides the heretofore undecided question of whether the act of defecating in one’s pants upon being informed of a pending criminal charge is a relevant fact for the jury.

That’s a heckuva way to get your reading audience’s attention. Here’s what happened:

The prosecutor elicited testimony from the arresting officer that, upon being informed he was under arrest for sexual child assault, the defendant defecated in his pants (although he denied doing so at trial). Defense counsel objected on relevancy grounds and the judge sustained the objection. The judge told the jury to disregard the comment. Oh yeah, I’m sure the jurors were able to just completely forget that little tidbit.

The defendant appealed, asserting a mistrial should have been granted. On appeal, the prosecutor argued that the defendant’s unseemly accident was admissible as an “excited utterance” under the rules of evidence.

“Excited utterance” is an exception to the rule the bars the introduction of hearsay testimony. Hearsay–that is, statements made outside of court–are, subject to many exceptions, barred because they are deemed untrustworthy. The basis for admitting an excited utterance into evidence is the belief that statements made under shock or surprise are likely to be trustworthy.

Judge Hardberger, writing for the Texas Court of Appeals, did an admirable job of fairly identifying the conflicting inferences that could be drawn from the alleged act by the defendant. After rejecting defendant’s argument that the act had no relevance, he wrote:

On the other hand, defecation in one’s pants upon arrest does not necessarily indicate guilt. Such an act could be evidence of the innocence of a man accused of a heinous crime he didn’t do … Granted, it could also be the act of a guilty person being found out. Or it could simply be the act of a man sick to his stomach.

The court determined that the trial judge’s instruction to the jury to disregard the testimony cured any possible error.

— Marles v. State, 919 S.W.2d 669, 670–71 (Tex. Crim. App. 1996). Thanks to David Keller.

October 31st, 2011  Does a court have personal jurisdiction over the Prince of Darkness? Depends where he lives. Does a court have personal jurisdiction over the Prince of Darkness? Depends where he lives.

In Mayo v. Satan and His Staff, the plaintiff filed a civil rights action alleging Satan and his employees “on numerous occasions caused plaintiff misery and unwarranted threats, against the will of plaintiff” and “placed deliberate obstacles in his path and caused plaintiff’s downfall.” Plaintiff asserted these transgressions violated his constitutional rights. He sought the court’s permission to proceed in forma pauperis.

U.S. District Judge Weber denied the application, noting several complicated legal issues the plaintiff’s lawsuit would raise (some paragraph breaks inserted):

Even if plaintiff’s complaint reveals a prima facie recital of the infringement of the civil rights of a citizen of the United States, the Court has serious doubts that the complaint reveals a cause of action upon which relief can be granted by the court.

We question whether plaintiff may obtain personal jurisdiction over the defendant in this judicial district. The complaint contains no allegation of residence in this district. While the official reports disclose no case where this defendant has appeared as defendant there is an unofficial account of a trial in New Hampshire where this defendant filed an action of mortgage foreclosure as plaintiff.

The defendant in that action was represented by the preeminent advocate of that day, and raised the defense that the plaintiff was a foreign prince with no standing to sue in an American Court. This defense was overcome by overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Whether or not this would raise an estoppel in the present case we are unable to determine at this time.

If such action were to be allowed we would also face the question of whether it may be maintained as a class action. It appears to meet the requirements of Fed.R. of Civ.P. 23 that the class is so numerous that joinder of all members is impracticable, there are questions of law and fact common to the class, and the claims of the representative party is typical of the claims of the class. We cannot now determine if the representative party will fairly protect the interests of the class.

We note that the plaintiff has failed to include with his complaint the required form of instructions for the United States Marshal for directions as to service of process.

For the foregoing reasons we must exercise our discretion to refuse the prayer of plaintiff to proceed in forma pauperis.

Hmm, that’s interesting that a plaintiff purporting to be the devil filed a mortgage foreclosure action way back in the day. Maybe that’s who’s behind the current mortgage meltdown.

— United States ex rel. Gerald Mayo v. Satan & His Staff, 54 F.R.D. 282, 283 (W.D. Pa. 1971).

October 31st, 2011  In Hormel Corp. v. Jim Henson Productions, Inc., Hormel sued the Muppet master for infringing the trademark of its delicious product SPAM® by naming a character in the 1996 movie, Muppet Treasure Island, “Spa’am.” The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York rejected Hormel’s claims and the Second Circuit affirmed. Among the highlights: In Hormel Corp. v. Jim Henson Productions, Inc., Hormel sued the Muppet master for infringing the trademark of its delicious product SPAM® by naming a character in the 1996 movie, Muppet Treasure Island, “Spa’am.” The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York rejected Hormel’s claims and the Second Circuit affirmed. Among the highlights:

• Hormel was worried that sales of SPAM would suffer if they were linked with Spa’am, the movie character, a wild boar puppet allegedly depicted as “evil in porcine form.” Not to worry. An expert in children’s literature persuaded the court that Spa’am, although not “classically handsome” and introduced as a threatening character at the beginning of the movie, ultimately becomes a positive character when he befriends the Muppets and helps them escape from the film’s villain, Long John Silver. Thank goodness we could find an expert in children’s literature to unravel that puzzle. Would that kind of testimony pass Daubert scrutiny?

• The court opined that Hormel should lighten up because, even though SPAM is a high-quality product, it is already the butt of jokes because of “the public’s unfounded suspicion that SPAM is the product of less than savory ingredients.” The court pointed out that in the television cartoon, Duckman, Duckman discovers the secret ingredient to SPAM as he gazes upon “Murray’s Incontinent Camel Farm.” The court also quoted a columnist who joked that SPAM contained all five major food groups: snouts, ears, feet, tails and brains. The court said that, given all the ribbing, “one might think Hormel would welcome the association with a genuine source of pork.”

• The court also rejected Hormel’s claim that Jim Henson Productions’ merchandising of the Spa’am character would interfere with Hormel’s own merchandising of SPAM, including its character, “SPAM-man,” a giant can of SPAM with arms and legs.

Hormel lost the case, but may have had the last laugh. It has sold more than five billion cans of SPAM . SPAM is eaten in 30 percent of American homes. I probably ate a thousand fried SPAM sandwiches when I was a kid, although I try not to think about it.

— Hormel Foods Corp. v. Jim Henson Prods., Inc., 73 F.3d 497, 501–02 (2d Cir. 1996). Thanks to Lihwei Lin.

October 31st, 2011  The intersection of church and tort law is an interesting area. For the most part, courts–wisely so–have been reluctant to entangle tort law with church and religion except in cases of intentional physical batteries. In Bass v. Aetna Ins. Co., the court had to decide whether “trotting under the Spirit of the Lord” in church, with the result of running into and injuring the plaintiff, was actionable or a protected “Act of God.” The intersection of church and tort law is an interesting area. For the most part, courts–wisely so–have been reluctant to entangle tort law with church and religion except in cases of intentional physical batteries. In Bass v. Aetna Ins. Co., the court had to decide whether “trotting under the Spirit of the Lord” in church, with the result of running into and injuring the plaintiff, was actionable or a protected “Act of God.”

Plaintiff attended the Shepard’s Fold Church in Louisiana, where moving or running in the aisles “in the Spirit” apparently is a common practice. During a revival, a fellow worshiper ran down the aisle where plaintiff was kneeling and praying and knocked her down, causing injury. Plaintiff sued for negligence.

At trial, the defendant testified he was “‘trotting’ under the Spirit of the Lord” and was not in control of his actions at the time of the collision. He raised “Act of God” as a defense and also asserted the plaintiff assumed the risk of the collision and was contributorily negligent. For non-legals, an Act of God under law is a harm-causing force of nature, such as a tornado or flood, the consequences of which humans generally are not held responsible for.

The trial court dismissed the case, finding that the plaintiff assumed the risk of the collision by praying in the aisle with her eyes closed, a decision affirmed by the court of appeals. But the Louisiana Supreme Court reversed.

The West headnote writers summed up the holdings succinctly:

[1] Negligence: Notwithstanding that worshiper testified he was trotting under the Spirit of the Lord, “Act of God” defense did not apply in action by worshiper who was injured while praying in the aisle against second worshiper who was running in church inasmuch as “Act of God” meant force majeure.

[14] Religious Societies: It is not contributory negligence to bow one’s head while praying in church, whether in the pew or in the aisle.

— Bass v. Aetna Ins. Co., 370 So. 2d 511 (La. 1979). Thanks to a fellow Torts professor.

October 31st, 2011 In Searight v. New Jersey, the plaintiff sued the State of New Jersey alleging that the state unlawfully injected him in the left eye with a radium electric beam. As a result, he asserted that someone began talking to him inside his brain.

The court rejected the claim as time-barred by the statute of limitations, but also observed that proper jurisdiction for unlicensed radio communications would lie with the FCC. The court also offered plaintiff a terribly insensitive self-help suggestion. Here’s an excerpt from the opinion:

The allegations, of course, are of facts which, if they exist, are not yet known to man. Just as Mr. Houdini has so far failed to establish communication from the spirit world …, so the decades of scientific experiments and statistical analysis have failed to establish the existence of ‘extrasensory perception’ (ESP). But, taking the facts as pleaded, and assuming them to be true, they show a case of presumably unlicensed radio communication, a matter which comes within the sole jurisdiction of the Federal Communications Commission, 47 U.S.C. § 151, et seq.

And even aside from that, Searight could have blocked the broadcast to the antenna in his brain simply by grounding it. See, for example, Ghirardi, Modern Radio Servicing, First Edition, p. 572, ff. (Radio & Technical Publishing Co., New York, 1935). Just as delivery trucks for oil and gasoline are ‘grounded’ against the accumulation of charges of static electricity, so on the same principle Searight might have pinned to the back of a trouser leg a short chain of paper clips so that the end would touch the ground and prevent anyone from talking to him inside his brain.

Sounds like poor Searight was suffering from schizophrenia. Schizophrenia is a cruel neurological brain disorder that affects 2.2 million Americans. Lawhaha.com is a fan of judicial humor, but this one never should have seen the light of day. Many of the most unusual and sometimes amusing judicial opinions occur because of the unusual or weird parties involved. But this court went out of its way to humuliate Searight. In fairness, it was 1976. Society has much more awareness of and sensitivity to mental illness, although we still have a long way to go. Schizophrenia.com is a good source info about the condition suffered by people like Searight.

— Searight v. New Jersey, 412 F. Supp. 413, 414–15 (D.N.J. 1976). Thanks to Lihwei Lin.

|

Funny Law School Stories

For all its terror and tedium, law school can be a hilarious place. Everyone has a funny law school story. What’s your story?

|

Product Warning Labels

A variety of warning labels, some good, some silly and some just really odd. If you come encounter a funny or interesting product warning label, please send it along.

|

Tortland

Tortland collects interesting tort cases, warning labels, and photos of potential torts. Raise risk awareness. Play "Spot the Tort." |

Weird Patents

Think it’s really hard to get a patent? Think again.

|

Legal Oddities

From the simply curious to the downright bizarre, a collection of amusing law-related artifacts.

|

Spot the Tort

Have fun and make the world a safer place. Send in pictures of dangerous conditions you stumble upon (figuratively only, we hope) out there in Tortland.

|

Legal Education

Collecting any and all amusing tidbits related to legal education.

|

Harmless Error

McClurg's twisted legal humor column ran for more than four years

in the American Bar Association Journal.

|

|

|

In this Halloween-themed case, the plaintiff bought a house, only to learn that it had a reputation in the Village of Nyack, NY, for being possessed by poltergeists, a reputation built in large part on the seller’s previous efforts to promote the house as haunted, which were unknown to plaintiff. On learning of the alleged haunting, plaintiff sued for rescission of the sale contract.

In this Halloween-themed case, the plaintiff bought a house, only to learn that it had a reputation in the Village of Nyack, NY, for being possessed by poltergeists, a reputation built in large part on the seller’s previous efforts to promote the house as haunted, which were unknown to plaintiff. On learning of the alleged haunting, plaintiff sued for rescission of the sale contract.