January 9th, 2015  Don’t think for a minute that Canadian judges can’t keep up with American judges when it comes to Strange Judicial Opinions. Wild and crazy judicial happenings in Canada are here, here and here. Don’t think for a minute that Canadian judges can’t keep up with American judges when it comes to Strange Judicial Opinions. Wild and crazy judicial happenings in Canada are here, here and here.

Now comes a new hit TV series, I mean, an order in a divorce case, entered by Superior Court Justice Pazaratz, where the court analogized the parties’ ugly divorce to the hit television show, Breaking Bad. Excerpts from the order include:

1. Breaking Bad, meet Breaking Bad Parents.

2. The former is an acclaimed fictional TV show whose title needed a bit of explaining: “BREAKING BAD: A southern U.S. expression for when a good person suddenly loses their moral compass and starts doing bad things”.

3. The latter is a sad reality show playing out in family courts across the country. “BREAKING BAD PARENTS: When smart, loving, caring, sensible mothers and fathers suddenly lose their parental judgment and embark on relentless, nasty litigation; oblivious to the impact on their children”.

4. SPOILER ALERT: The main characters in both of these tragedies end up pretty much the same: Miserable. Financially ruined. And worst of all, hurting the children they claimed they were protecting.

5. To prolong the tortured metaphor only slightly, the “urgent” motion before me might be regarded as this family’s pilot episode. Will these parents sign up for the permanent cast of Breaking Bad Parents? Will they become regulars in our family court building, recognizable by face and disposition? Or will they come to their senses; salvage their lives, dignity (and finances); and give their children the truly priceless gifts of maturity and permission to love.

6. Stay tuned.

[The court proceeds to recount the parties’ inability to work together, accusations and counter-accusations, and their deadlock in trying to reach a custody sharing arrangement. The Court decides on a reasonable arrangement before wrapping things up.]

36. One final comment:

37. I hope I didn’t offend the parties with my Breaking Bad Parents analogy. They’re not bad parents. Yet.

38. Mainly, I was trying to give both parties a sobering warning: Stop!

39. Stop being nasty.

40. Stop jockeying for position.

41. Stop playing hardball.

42. Stop acting like you hate your ex more than you love your children.

All good advice, Justice Pazaratz, but you’ve just ruined the potential for the TV series.

–Coe v. Tope, Case No. 2839/14, Ontario Superior Court of Justice (July 3, 2014). Thanks to whoever sent this along. We lost track of the original email. Let us hear from you!

June 24th, 2012 Maybe there should be an opposite abbreviation to TMI such as NEI (not enough information).

In a case involving a challenge to nuclear waste fees at a site intended to replace the Yucca Mountain disposal site, brought to our attention by way of The BLT: The Blog of LegalTimes, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia admonished the lawyers – in the attention-stealing first footnote no less – for using too many acronyms:

1. We also remind the parties that our Handbook of Practice and Internal Procedures states that “parties are strongly urged to limit the use of acronyms” and “should avoid using acronyms that are not widely known.” Brief-writing, no less than “written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble.” George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language,” 13 Horizon 76 (1946). Here, both parties abandoned any attempt to write in plain English, instead abbreviating every conceivable agency and statute involved, familiar or not, and littering their briefs with references to “SNF,” “HLW,” “NWF,” “NWPA,” and “BRC” – shorthand for “spent nuclear fuel,” “highlevel radioactive waste,” the “Nuclear Waste Fund,” the Nuclear Waste Policy Act,” and the “Blue Ribbon Commission.”

Who knew there was a written court rule against acronyms or that George Orwell gave legal-writing advice?

— Nat’l Ass’n of Regulatory Utility Commissioners v. U.S. Dep’t of Energy, Case No. 11-1066 (D.C. Cir., June 1, 2012)

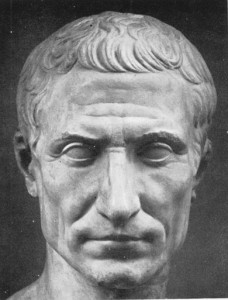

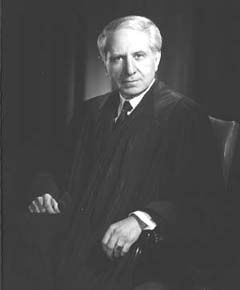

December 29th, 2011  Expert's testimony had more holes in it than this guy. In December 2011, the U.S. Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, per Judge Richard Posner, reversed a jury verdict in favor of an airline against Fed Ex for $65,998,411, the precise amount the airline had requested in damages.

One issue was the admissibility of complex testimony regarding the damages calculations by the airline’s expert witness, a forensic accountant named Morriss. Posner was not impressed by the expert’s regression analysis testimony:

Morriss’s regression had as many bloody wounds as Julius Caesar when he was stabbed 23 times by the Roman Senators led by Brutus. We have gone on at such length about the deficiencies of the regression analysis in order to remind district judges that, painful as it may be, it is their responsibility to screen expert testimony, however technical; we have suggested aids to the discharge of that responsibility. The responsibility is especially great in a jury trial, since jurors on average have an even lower comfort level with technical evidence than judges. The examination and cross-examination of Morriss were perfunctory and must have struck most, maybe all, of the jurors as gibberish. It became apparent at the oral argument of the appeal that even ATA’s lawyer did not understand Morriss’s analysis; he could not answer our questions about it but could only refer us to Morriss’s testimony.

Posner continued, saying: “If a party’s lawyer cannot understand the testimony of the party’s own expert, the testimony should be withheld from the jury. Evidence unintelligible to the trier or triers of fact has no place in a trial.” Posner suggested the reason the jurors returned a verdict for the exact amount, to the penny, that the airline sought was because they had no clue how to compute the damages.

That all makes perfect sense, but I feel for both the trial judge and the airline’s lawyer–and, of course, the jurors.

Trial judges are required to prescreen expert testimony for reliability, but that’s often practically impossible in highly technical areas such as engineering, medicine, and, in this case, regression analyses. The lawyers aren’t in much better of a position.

Judges and lawyers are smart and have well-developed critical-thinking skills, but those qualities don’t enable them to magically master bodies of technical knowledge in which they have no training. Many scholars have proposed enlisting expert judges and juries in technical, complex cases.

Of course, in the end, Posner was right. If an expert can’t explain how he how arrived at his conclusions in a way that laypersons–including judges and lawyers–can understand, the testimony should be excluded.

—ATA Airlines, Inc. v. Federal Express Corp., Case Nos. 11-1382, 11-1492, 7th Cir., Dec. 27, 2011. Thanks to Larry Buser.

November 27th, 2011 You know a judicial document is going to be a great read when it is captioned:

Order Denying MAAF’s Motion to Preclude the French Phrase ”Quel Jeu Doit-on Jouer Vis-à-vis des Autorités de Californie?” From Being Translated as “What Game Must We Play With the California Authorities?”

This opinion from U.S. District Judge A. Howard Matz (C.D. Cal.) stemmed from the judge’s frustration in overseeing a series of over-litigated lawsuits arising from the collapse of a California insurance company. The motion giving rise to the order, after all, was the twentieth motion in limine the judge had addressed in recent days.

Judge Matz seemed irritated that “some of the French litigants caught up in these complicated cases are still coping with the ‘mystifying’ peculiarities of American courts. They appear to assume, for example, that no judge is capable of using common sense (and perhaps some pre-existing familiarity with French) to understand a straightforward French phrase.”

The motion turned on the meaning of the French word “jeu” in a document addressed to one of the French defendants. The document posed a question: “Quel jeu doit-on jouer vis-à-vis des autorités de Californie?” The California Insurance Commissioner’s expert asserted the question translates to: “What game must we play with the California authorities?” The defendant’s expert claimed it means: “What approach must we take with the California authorities?”

Judge Matz accused the defendant’s expert of playing games with the court (paragraph breaks inserted):

If M. Simonet [composer of the document] was not speaking about a “game,” surely Ms. Zarelli [defendant’s expert translator] is playing one. The problems with her declaration are abundant. First, she relies only on a French-to-French dictionary. Wouldn’t the fairest, most reliable way to ascertain the correct English meaning of “jeu,” as M. Simonet used it, be to consult a French to English dictionary?

That’s what the Commissioner’s expert translator does: she points to Harrap’s Shorter Dictionnaire. . . . And what does that more reliable source reveal? Zut alors! Of the many definitions and examples of how “jouer” and “jeu” are translated, almost all are perfectly consistent with how “jeu” was translated in the document that MAAF seeks to keep out: as a “game,” and often with a connotation of “trickery.” Harrap’s even translates “jouer le jeu” as “to play the game.” It translates other examples of the use of “jeu” into such familiar, straightforward English words andphrases as “all this fooling around;” “what’s your game?;” “to play into one’shands . . ..”

Moreover, as the Commissioner’s language expert points out, the definition that Ms. Zarelli happened to choose — “manière d! agir” — includes, if one bothers to take the complete entry into account, which Ms. Zarelli did not do — “manège” and “stratagème.” The connotations of those terms are hardly helpful to MAAF; they mean “ploy” or “trick.” In short, both the literal meaning and the context in which M. Simonet asked his not-so-rhetorical question “Quel jeu doit- on jouer vis-à-vis des autorités de Californie?” is entirely consistent with “What game must we play with the California authorities?”

Judge Matz must have been enjoying himself by this point because he added a closing footnote comparing the bravery and last name of the plaintiff’s lawyer—one “Ney”—to “Ney, the Duc d’Elchingen and Prince de la Moskova,” an army commander who Napoleon once called “the bravest of the brave.”

What did the lawyer do that was so brave? He had the nerve (“considerable fortitude,” as Matz put it) to file what the judge considered to be a ridiculous motion.

— Garamendi v. Altus Fin. S.A., Case No. CV-99-2829 (CWx) (C.D. Cal, Feb. 10, 2005). Thanks to Michael Barclay

November 27th, 2011  When one is not enough. Wait. That’s not right. It’s Judge Jacob Hart of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. Can’t be too careful about those typos. Just ask the plaintiff’s lawyer in Devore v. City of Philadelphia.

Judge Hart reduced his attorney’s fee award by $60,000 based on the poor quality of his written work, which, according to the judge, was “careless to the point of disrespectful.” The defendants described it even less charitably, as “vague, ambiguous, unintelligible, verbose and repetitive.” And those were the things they liked about it. Kidding.

The court noted that throughout the litigation, counsel identified the court as: “THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTER [sic] DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA,” adding that “[c]onsidering the religious persuasion of the presiding officer, the ‘Passover District’ would have been more appropriate.”

The priceless part (and what elevated the case into the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame) was the lawyer’s written response to the assertion that his fees should be reduced because of typos:

As for there being typos, yes there have been typos, but these errors have not detracted from the arguments or results, and the rule in this case was a victory for Mr. Devore. Further, had the Defendants not tired [sic] to paper Plaintiff’s counsel to death, some type [sic] would not have occurred. Furthermore, there have been omissions by Defendants, thus they should not case [sic] stones.

Judge Hart said that the above errors would have been “brilliant” if intentional, but that, based on the lawyer’s filings, “we know otherwise.”

Concluding that the lawyer’s filings wasted a lot of the court’s and the defendants’ time, the court halved the lawyer’s requested hourly rate from $300 per hour to $150. Non-lawyers might consider it amusing that a lawyer whose work is so poor that the court publicly disses him could still earn $150 an hour, but to be fair to the lawyer, he obtained a good result in the case for his clients. Also, the judge commended him for his in-court work.

May this case be a lesson to all law students out there who discount the value of their legal writing courses, not to mention their eighth-grade English courses. Cheers for Judge Hurt.

— Devore v. City of Philadelphia, No. 00-3598, 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 3635, at *7–8 (E.D. Pa., Feb. 20, 2004). Thanks to Cynthia Cohan and Professor Howard Wasserman.

November 27th, 2011 The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure permit any electronic document to be e-filed until midnight on the due date. Microsoft electronically filed a motion for summary judgment 4 minutes and 27 seconds late on the night of June 26, 2003.

Microsoft’s adversary in the litigation, Hyperphase Technologies, Inc., incensed by this grievous rule breach, filed a motion to strike the motion for summary judgment as untimely.

U.S. Magistrate Stephen L. Crocker, clearly annoyed, blessed us with this sarcastic order:

In a scandalous affront to this court’s deadlines, Microsoft did not file its summary judgment motion until 12:04:27 a.m. … I don’t know this personally because I was home sleeping, but that’s what the court’s computer docketing program says, so I’ll accept it as true.

Microsoft’s insouciance so flustered Hyperphase that nine of its attorneys [names omitted] promptly filed a motion to strike …. Counsel used bolded italics to make their point, a clear sign of grievous inequity by one’s foe. True, this court did enter an order … ordering the parties not to flyspeck each other, but how could such an order apply to a motion filed almost five minutes later? Microsoft’s temerity was nothing short of a frontal assault on the precept of punctuality so cherished by and vital to this court.

Wounded though this court may be by Microsoft’s four minute and twenty-seven second dereliction in duty, it will transcend the affront and forgive the tardiness. Indeed, to demonstrate the evenhandedness of its magnanimity, the court will allow Hyperphase on some future occasion in this case to e-file a motion four minutes and thirty seconds late ….

— Hyperphrase Techs., Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 56 Fed. R. Serv. 3d (Callaghan) 467 (W.D. Wis. 2003). Thanks to Cynthia Cohan.

November 26th, 2011 Thanks to Oregon Circuit Judge G. Philip Arnold for sending us Franklin v. Oregon. The opinion details the plight of Oregon federal district Judge James M. Burns and a unique prison inmate named Harry Franklin back in 1983. Their longterm relationship was on the rocks when Burns penned these opening words:

This is another chapter in the Harry Franklin saga. No longer am I tempted to call it the final chapter, as desirable as that would be to me. I mention mournfully that only the finality of death—his or mine—would enable the other of us to use the term “final” in that way. And, of course, if mine comes first, I have no doubt that another judge will someday express lamentations such as these.

Franklin was a prolific inmate litigator. Burns had already dismissed 37 cases he filed, only to receive two dozen more. These were on top of 45 other lawsuits filed by the inmate, which were dealt with by a different judge.

Here are some of the claims Judge Burns had to contend with:

– A claim for $3 million damages for mental frustration suffered by Franklin when a Portland television station allegedly misidentified a “14 wheeler tractor and trailer rig” as an “18 wheeler.”

– A claim for “Harassment by Water” arising from the Oregon State Prison’s sprinkling of the prison yard during summer months, which prevented Franklin from finding a dry place to lie down.

– A claim that the Oregon State Prison wrongfully bakes its desserts in aluminum rather than stainless steel pans.

How did the inmate decide which of his claims had merit? In his words:

FN1. “The Lord spoke to me, and he told me to file these lawsuits and said, ‘You will win big in your lawsuits,’” the heavy-set, white haired convict said. “He showed me an enormous elephant. He said that the elephant represents the big, gray courts, which is the government. Anyway, I was leading this elephant through every section of this penitentiary,” he said. “I was writing on a yellow legal pad. Each place we came to I’d jot something down and slap the sheet onto the elephant. And they all stuck. The Lord told me the sheets were suits. I never could get over that monstrous elephant.”

— Franklin v. Oregon, 563 F. Supp. 1310, 1316–17 & n.1 (D. Or. 1983). Thanks, Judge.

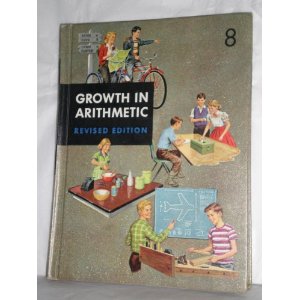

November 24th, 2011  Eighth-grade math book held to be controlling authority by a federal appellate court. You gotta love an opinion that begins:

In this appeal we are asked to determine whether “.82″ is the equivalent of “82%.” Having successfully completed grammar school, we are able to answer the question in the affirmative.

An unsuccessful bidder for an offshore oil and gas lease brought suit against the Secretary of the Interior for awarding the contract to a competitor. The plaintiff offered a royalty of “73.45689%” in its bid. A competitor offered a royalty bid of “.82165.” The Secretary construed the competitor’s bid as one for 82.165 percent, and awarded the contract to it based on it being the higher bid.

The plaintiff asserted the Secretary acted arbitrarily and capriciously in construing .82165 to be 82.165 percent. The trial court agreed and entered judgment for the plaintiff.

The U.S. Court of Appearls for the Fifth Circuit reversed, relying on as its primary source of authority an eighth-grade math book called “Growth in Arithmetic,” which the Court said asked and answered the pertinent question: “Do you know how to change a per cent to a decimal?”

— Oil & Gas Futures, Inc. of Tex. v. Andrus, 610 F.2d 287, 287–88 (5th Cir. 1980). Thanks to Frank Zotter.

November 20th, 2011 A federal judge in Oklahoma, annoyed by delays in carrying out his order to commit a defendant to a medical facility, managed to maintain a perfect judicial temperament and sense of humor on hearing the news that the parties had worked out everything out on their own–without bothering to tell the judge. His “on the one hand, but on the other hand” order is a masterpiece of balance and even-handedness.

“On the one hand,” the court was grateful that the government and the defendant were able to cooperate in setting a date for the defendant to report.

“On the other hand,” the court said, “the court might be somewhat justified in experiencing annoyance at being left out of the loop in making a decision that is vested in its sound discretion. ‘Oh right, somebody better remember to tell the judge…’”

“On the one hand,” the court wanted to give due consideration to the fact that the defendant was 80 years old and was receiving treatment for a heart condition by a neurosurgeon.

“On the other hand,” the court asked, “how long may a defendant avoid imposition of justifiable court orders merely because of his age and medical condition? Where does it end? Anarchy? Dogs and cats living together?”

In the end, the court threw in the towel and agreed to let the defendant report on the date agreed to by the government. Or as the court put it: “[T]he court will be content to let imposition of its orders be held hostage by the vagaries of the schedule of some neurosurgeon in Oklahoma City.”

— Order, United States v. Stipe, Case No. 07-TP-001-RAW (E.D. Okla., May 5, 2008). Thanks to Debra Schwartz.

November 18th, 2011 As Paul Scott wrote when he sent in a federal district court opinion involving an excessive force claim against a Georgia police officer, it’s not too hard to figure out which side’s going to win the case when the court’s decision starts out by measuring the plaintiff’s sprained-wrist claim against “the rights of those thousands of American soldiers” who fought and died on D-Day in World War II:

This case demonstrates the proclivity of American citizens today to search for legal causes of action to redress every imaginable wrong. As we commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Allied’s invasion of Normandy during World War II, the Court must decide in this case whether the rights those thousands of American soldiers fought and died for on the beaches of France include legal recourse for a sprained wrist suffered by someone who was arrested for, and subsequently convicted of, the obstruction of a law enforcement officer.

Surprise! The plaintiff lost (the court granted defendant’s motion for summary judgment).

— Mladek v. Day, 320 F. Supp. 2d 1373, 1374 (M.D. Ga. 2004). Thanks to Paul Scott.

November 18th, 2011 Several grounds exist for a judge denying a lawyer’s motion. Now we have a new one: incomprehensibility.

Displeased with a lawyer’s inartful motion-drafting, U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Leif M. Clark (W.D. Tex.) entered an order captioned “Order Denying Motion for Incomprehensibility.” The judge couldn’t figure out what the heck the defendant was requesting in a motion titled, “Defendant’s Motion to Discharge Response to Plaintiff’s Response to Defendant’s Response Opposing Objection to Discharge.”

Judge Clark said: “The court cannot determine the substance, in any, of the Defendant’s legal argument, nor can the court even ascertain the relief that the Defendant is requesting. The Defendant’s motion is accordingly denied for being incomprehensible.”

Perhaps worried that the defendant might miss his point, Judge Clark appended a footnote in which he invoked the following quotation from the Adam Sandler movie, Billy Madison:

Mr. Madison [Sandler’s character], what you’ve just said is one of the most insanely idiotic things I’ve ever heard. At no point in your rambling, incoherent response was there anything that could even be considered a rational thought. Everyone in this room is now dumber for having listened to it. I award you no point, and may God have mercy on your soul.

— Order Denying Motion for Incomprehensibility, In re King, Case No. 05-56485-C, Feb. 21, 2006. Thanks to Sharee Moser.

November 17th, 2011 You don’t have to be a famous judge or blessed with a crazy case to write a Hall of Fame Strange Judicial Opinion. Here we have a low-level New Zealand trial judge trying to educate his appellate court masters about life down in the “real world” trial court-trenches, and a good-humored, self-effacing reply from the appellate court.

In New Zealand, an appeal over a $100 fine for failure to register “a handsome German Shepherd named Ben” apparently irritated the overworked trial judge. In a memorandum, the judge sought to educate the high court about the process for administering justice in his humble court at the bottom of the judicial hierarchy:

Your honour may not be familiar with the manner in which “Minor Offences” are dealt with in this Court. Notices of Prosecution . . . are surreptitiously placed in the Judge’s “In Tray” at frequent and irritating intervals, usually in his or her absence. They come in stacks and bundles … [The trial judge proceeds to describe the variety of matters crying out for his daily attention, including applications for Massage Parlor licenses, truancy notices, underage drinking citations, etc.]

The Judge peruses the mountain of files with great care and then imposes whatever he or she deems appropriate. No hearing is held. No defendant or counsel are present. No submissions are made. No tears are shed. No howls of derision are heard from the gallery. … No anxious mother suckles a fretful child. There are no sideways glances or rolling back of eyes from counsel’s table and certainly no titters are heard to run around the Court.

The Judge sits alone in his chambers and affixes his facsimile signature to the Information Sheet perhaps muttering silent curses to himself as he does so. …

I hope this short memorandum may assist Your Honour in dealing with this appeal.

High Court Justice Grant Hammond (pretty sure this is him–please correct if wrong), chragined, contrasted the trial judge’s mundane existence with the grandeur of his much more regal appellate court, describing how on the day of the hearing over the hundred-dollar appeal, “[i]n full High Court regalia we processed bewigged and black-robed through several levels” of the court building.

It was clear Justice Hammond felt awkward about “tinkering” with the trial judge’s work. He quoted political philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s description of court systems as “a fathomless and boundless chaos, made up of fiction, tautology, technicality and inconsistency, and the administration of it a system of exquisitely contrived chicanery which maximises delay and the denial of justice.”

In the end, Hammond’s court reduced the fine to $20 because the appellant didn’t have the money to pay the higher fine.

— Lowe v. Auckland City Council (High Court, Auckland, AP44/93, 12 May 1993, Hammond, J.). Thanks to Lina Lim.

November 16th, 2011 U.S. District Judge Richard P. Matsch awarded attorneys’ fees and costs in a patent infringement case against a pair of high-echelon lawyers and their clients for trial misconduct “reflecting an attitude of ‘what can I get away with?’” and a “winning is all that is important approach” to litigation. A media report estimated the fees and costs could run several million dollars. Judge Matsch had previously thrown out the plaintiffs’ $51 million verdict in the case based on the same conduct.

The case raises interesting questions about the extent of a judge’s obligation to control attorney conduct it finds objectionable during the course of a trial.

The facts are complicated and readers interested in the full story should consult the judge’s order. But basically, the judge was ticked off that the plaintiffs’ lawyers pursued a trial strategy that the judge considered legally untenable, including attempting to establish a patent infringement by showing substantial similarity between the plaintiffs’ product and the defendants’ product.

Judge Matsch opined (paragraph breaks inserted):

Upon reflection, this Court finds and concludes that the rulings on the claims construction issues adjudicated the fairly debatable issues in this case and that the manner in which plaintiffs’ counsel continued the prosecution of the claims through trial was in disregard of their obligations as officers of the court.

The fairness of the adversary system of adjudication depends upon the assumption that trial lawyers will temper zealous advocacy of their client’s cause with an objective assessment of its merit and be candid in presenting it to the court and to opposing counsel.

When that assumption has been contradicted by a trial record of conduct reflecting a winning is all that is important approach to the trial process, the court has a duty to redress this resulting harm to the opposing party.

Judge Matsch essentially took the position that the plaintiffs’ claims were frivolous. However, he had previously denied the defendants’ motion for summary judgment and the jury returned a verdict in the plaintiffs’ favor. Defendants argued that these events showed the claims had merit, but the judge disagreed.

Perhaps most interesting was the defendants’ argument that if the judge found the trial conduct to be objectionable, he should have done something about it during the trial. In the judge’s words, the plaintiff’s lawyers “argue that they should not be held responsible for what they were able to get away with during the trial presentation.”

The argument does carry some persuasive force, particularly since the judge apparently denied objections by defendants’ counsel to some of the misconduct.

But Judge Matsch took the position that counsel were already aware of the court’s admonitions regarding the trial strategy, so he didn’t have any obligation to restrain it during the trial.

— Medtronic Navigation, Inc. v. Brainlab Medizinische Computersystems GMBH, No. 98-cv-01072-RPM, 2008 WL 410413 (D. Colo. 2008).

November 14th, 2011  Justice Michael Musmanno, a Lawhaha.com Hall of Famer Any fan of judicial opinion writing needs to study the opinions of the Honorable Michael A. Musmanno (1897-1968). He led a remarkable life. Before joining the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, Justice Musmanno enjoyed an illustrious career as a lawyer, U.S. Congressman and author. Highlights of his career include serving as the presiding judge at the Nuremberg war crime trials and as a defense lawyer in the Sacco & Vanzetti trial.

His opinions are marvelous concoctions of deep-hearted passion and brutal common sense, delivered in highly literate and often hilarious prose.

U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Alex Kozinski, another notable opinion-writer, reported to Lawhaha.com that Musmanno has been his model since law school and that he consciously tries to emulate Musmanno’s writing. He laments that today’s law school graduates have never heard of Musmanno and return only blank stares when his name is mentioned.

Here are a couple samples of Musmanno’s writing sent by Chris Nace:

In Bosley v. Andrews, a woman sued a neighbor whose cows trespassed on her farmland to eat her crops. After being chased away in the morning, the “bovine buccaneers,” as Musmanno called them, returned for lunch. “This time they came, eight of them, with reinforcements. They brought along their boy friend, a 1500-pound Hereford white-faced bull.” The bull took chase after the plaintiff, causing her to suffer a heart attack.

A majority of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court rejected the woman’s claim for negligent infliction of emotional distress damages, following the traditional rule that such a claim cannot be maintained in the absence of a “physical impact” with the plaintiff (the bull never actually touched the plaintiff).

In dissent, Musmanno skewered the majority for what he saw as an unjust result, closing his opinion by stating that the majority’s approach “is unsupportable in law, logic, and elementary justice – and I shall continue to dissent from it until the cows come home.”

In Pennsylvania Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals v. Bravo Enterprises, Inc., the plaintiff sought to enjoin a bullfight, but the majority held that the organization lacked standing. Musmanno began his impassioned dissent:

If there is one commodity of which there is no need for a further supply, it is violence. If there is one school that the world can afford to miss, it is one for the tutoring of methods of violence, brutality and cruelty. … [W]e can well do without a bullfight which is nothing less than an open air lyceum in the art of torturing helpless animals.

Add Justice Musmanno to your list of “four dead people with whom you would most like to have dinner.”

— Bosley v. Andrews, 142 A. 2d 263, 267–68, 280 (Pa. 1958) (Musmanno, J., dissenting); Pa. Soc’y for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals v. Bravo Enterprises, Inc., 237 A. 2d 342 (Pa. 1968) (Musmanno, J., dissenting). Thanks to Chris Nace.

November 14th, 2011 The classic dilemma of the law. Which is more important: following the rules or dispensing justice? Being faithful to precedent or willing to bend technical legal rules to reach the correct result?

We struggle with these issues from the time we’re first-year law students. Rules won out in ugly fashion in In re Estate of Pavlinko.

Vasil Pavlinko and his wife, Hellen, immigrants who spoke little English, went to a lawyer to have separate wills drawn up. Both wills left their residual interest to the same person: Elias Martin, the brother of Hellen Pavlinko. Unfortunately, when it came time to sign the wills, the wills got mixed up and Vasil and Hellen each signed the other’s will.

After the couple died, Elias Martin—the sole residuary legatee under both wills—offered Vasil’s will for probate. Although conceding that the result was “unfortunate,” the Pennsylvania Supreme Court rejected Martin’s petition because Vasil had mistakenly signed Hellen’s will.

Judge Michael Angelo Musmanno, a Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Famer for his intelligent prose, dissented, in an impassioned Ode to Screwing Up:

Everyone in this case admits that a mistake was made: an honest, innocent, unambiguous, simple mistake, the innocent, drowsy mistake of a man who sleeps all day and, on awakening, accepts the sunset for the dawn.

Nothing is more common to mankind than mistakes. Volumes, even libraries have been written on mistakes: Mistakes of law and mistakes of fact. In every phase of life, mistakes occur and there are but few people who will not attempt to lend a helping hand to the person who mistakes a step for a landing and falls, or the one who mistakes a nut for a grape and chokes, or the one who steps through a glass so clear that he does not see it. This Court, however, says that it can do nothing for the victim of the mistake in this case, a mistake which was caused through no fault of his own, nor of his intended benefactors.

… I know that the law is founded on precedent and in many ways we are bound by the dead hand of the past. But even with obeisance to precedent, I still do not believe that the medicine of the law is incapable of curing the simple ailment here ….

We have said more times than there are tombstones in the cemetery where the Pavlinkos lie buried, that the primary rule to be followed in the interpretation of a will is to ascertain the intention of the testator. Can anyone go to the graves of the Pavlinkos and say that we do not know what they meant? They said in English and Carpathian that they wanted their property to go to Elias Martin.

— In re Estate of Pavlinko, 148 A. 2d 528, 532 (Pa. 1959) (Musmanno, J., dissenting). Thanks to Frank Zotter.

November 13th, 2011 In U.S. v. Ramirez Lopez, the defendant was convicted of smuggling aliens into the U.S. from Mexico. One died during the journey due to inclement weather. When border patrol agents interviewed fourteen members of the group, two of them said the defendant was the guide of the expedition while the other twelve exculpated him, denying he was the guide.

The government deported nine of the twelve exculpatory witnesses back to Mexico prior to trial and the trial judge denied admission of the government’s interview notes with them.

It’s fair to say Judge Kozinski was unimpressed by the fairness of the procedure. He began his dissent from the affirmance of the conviction with a satirical, fictional post-trial conversation between the defendant and his lawyer:

Lawyer: Juan, I have good news and bad news.

Ramirez-Lopez: OK, I’m ready. Give me the bad news first.

Lawyer: The bad news is that the Ninth Circuit affirmed your conviction and you’re going to spend many years in federal prison.

Ramirez-Lopez: Oh, man, that’s terrible. I’m so disappointed. But you said there’s good news too, right?

Lawyer: Yes, excellent news! I’m very excited.

Ramirez-Lopez: OK, I’m ready for some good news, let me have it.

Lawyer: Well, here it goes: You’ll be happy to know that you had a perfect trial. They got you fair and square!

[Colloquy continues in which the defendant questions the fairness of the trial and the judge explains the harmless error rule as “No harm, no foul.” The defendant takes issue with the “no harm” part, pointing out he had twelve witnesses who said he wasn’t the guide, but the government sent nine of them back to Mexico. The lawyer assures him the government talked to all of them and took good notes about what each one said.]

Ramirez-Lopez: No kidding, man. They did all that for me?

Lawyer: They sure did. Is this a great country or what?

Ramirez-Lopez: OK, I see it now, but there’s one thing that still confuses me.

Lawyer: What’s that, Juan?

Ramirez-Lopez: You see, the government took all those great notes to help me, just so we’d know what all those guys said.

Lawyer: Right, I saw them, and they were very good notes. Clear, specific, detailed. Good grammar and syntax. All told, I’d say those were some great notes.

Ramirez-Lopez: And twelve of those guys all said I wasn’t the guide.

Lawyer: Absolutely! Our government never hides the ball. The government of Iraq or Afghanistan or one of those places might do this, but not ours. If twelve guys said you weren’t the guide, everybody knows about it.

Ramirez-Lopez: Except the jury. I was there at the trial, and I remember the jury never saw the notes. And the officers who testified never told the jury that twelve of the fourteen guys that were with me said I wasn’t the guide.

Lawyer: Right.

Ramirez-Lopez: Isn’t the jury supposed to have all the facts?

Lawyer: Not all the facts. Some facts are cumulative, others are hearsay. Some facts are both cumulative and hearsay.

Ramirez-Lopez: Can you say that in plain English?

Lawyer: No.

Ramirez-Lopez: The jury was supposed to decide whether I was the guide or not, right? Don’t you think they might have had a reasonable doubt if they’d heard that twelve of the fourteen guys in my party said it wasn’t me?

Lawyer: He-he-he! You’d think that only if you didn’t go to law school. Lawyers and judges know better. It makes no difference at all to the jury whether one witness says it or a dozen witnesses say it. In fact, if you put on too many witnesses, they might get mad at you and send you to prison just for wasting their time. So the government did you a big favor by removing those nine witnesses before they could screw up your case.

Ramirez-Lopez: I see what you mean. But how about the notes? Surely the jury would have gotten a different picture if they had just seen the notes of nine guys saying I wasn’t the guide. That wouldn’t have taken too long.

Lawyer: Wrong again, Juan! Those notes were hearsay and in this country we don’t admit hearsay.

Ramirez-Lopez: How come?

Lawyer: The guys writing down what the witnesses said could have made a mistake.

Ramirez-Lopez: You mean, like maybe one of those twelve guys said, “Juan was the guide,” and the guy from Immigration made a mistake and wrote down, “Juan was not the guide”?

Lawyer: Exactly.

Ramirez-Lopez: You’re right again, it probably happened just that way. I bet those guys from Immigration wrote down, “Juan wasn’t the guide,” even when the witnesses said loud and clear I was the guide-just to be extra fair to me.

Lawyer: Absolutely, that’s the kind of guys they are.

Ramirez-Lopez: You’re very lucky to be working with guys like that.

Lawyer: Amen to that. I thank my lucky stars every Sunday in church.

Ramirez-Lopez: I feel a lot better now that you’ve explained it to me. This is really a pretty good system you have here. What do you call it?

Lawyer: Due process. We’re very proud of it.

This is the kind of intelligent humor–using humor or satire as a rhetorical device to make a point–that Lawhaha.com values, and a reason Judge K is in the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

— United States v. Ramirez Lopez, 315 F.3d 1143, 1159–62 (9th Cir. 2003) (Kozinski, J., dissenting). Thanks to Steven Druckenmiller.

November 6th, 2011  Appellate court doesn't like drug agents talking like this guy. In suppressing evidence in a drug case, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit had some harsh words for the federal drug agents who were involved. The Court also did not take kindly to the trial judge threatening to put one of the lawyers in jail for failing to answer phone calls from the court reporter about a disputed bill.

But first, the court’s indictment of Dragnet-ese. The court did not like the way the drug agents talked, as it explained in a footnote (paragraph breaks inserted):

1. The agents involved speak an almost impenetrable jargon. They do not get into their cars; they enter official government vehicles. They do not get out of or leave their cars, they exit them. They do not go somewhere; they proceed. They do not go to a particular place; they proceed to its vicinity. They do not watch or look; they surveille. They never see anything; they observe it. No one tells them anything; they are advised.

A person does not tell them his name; he identifies himself. A person does not say something; he indicates. They do not listen to a telephone conversation; they monitor it. People telephoning to each other do not say “hello;” they exchange greetings. An agent does not hand money to an informer to make a buy; he advances previously recorded official government funds.

To an agent, a list of serial numbers does not list serial numbers, it depicts Federal Reserve Notes. An agent does not say what an exhibit is; he says that it purports to be. The agents preface answers to simple and direct questions with “to my knowledge.” They cannot describe a conversation by saying “he said” and “I said;” they speak in conclusions. Sometimes it takes the combined efforts of counsel and the judge to get them to state who said what.

Under cross-examination, they seem unable to give a direct answer to a question; they either spout conclusions or do not understand. This often gives the prosecutor, under the guise of an objection, an opportunity to suggest an answer, which is then obligingly given.

As a side issue, the opinion contains a lengthy discussion of an incident in which the trial judge humiliated one of the defense lawyers in court and threatened to send him to jail for raising questions about the court reporter’s fee. The court reporter, who charged by the page, indented the text on each page so it began in the middle of the page, used only 25 lines of type per page instead of the standard 28, and used a font that was larger than normal. The lawyer tried to present an affidavit establishing that the transcript was twice as long as it needed to be, and thus twice as costly. The judge’s response? Here’s a snippet:

MR. LANGER (defense counsel): You say you spoke to me?

THE REPORTER: No. [TO JUDGE:] He wouldn’t even answer my phone calls.

MR. LANGER: Your Honor–

THE COURT: I know it. That is another thing. I ought to throw you in jail for not doing that, for not answering the phone calls of the reporter.

The Ninth Circuit disapproved of the trial judge’s conduct.

— United States v. Marshall, 488 F.2d 1169, 1171 n.1, 1200 (9th Cir. 1973). Thanks to Frank Zotter.

|

Funny Law School Stories

For all its terror and tedium, law school can be a hilarious place. Everyone has a funny law school story. What’s your story?

|

Product Warning Labels

A variety of warning labels, some good, some silly and some just really odd. If you come encounter a funny or interesting product warning label, please send it along.

|

Tortland

Tortland collects interesting tort cases, warning labels, and photos of potential torts. Raise risk awareness. Play "Spot the Tort." |

Weird Patents

Think it’s really hard to get a patent? Think again.

|

Legal Oddities

From the simply curious to the downright bizarre, a collection of amusing law-related artifacts.

|

Spot the Tort

Have fun and make the world a safer place. Send in pictures of dangerous conditions you stumble upon (figuratively only, we hope) out there in Tortland.

|

Legal Education

Collecting any and all amusing tidbits related to legal education.

|

Harmless Error

McClurg's twisted legal humor column ran for more than four years

in the American Bar Association Journal.

|

|

|

Don’t think for a minute that Canadian judges can’t keep up with American judges when it comes to Strange Judicial Opinions. Wild and crazy judicial happenings in Canada are here, here and here.

Don’t think for a minute that Canadian judges can’t keep up with American judges when it comes to Strange Judicial Opinions. Wild and crazy judicial happenings in Canada are here, here and here.