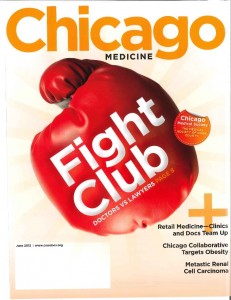

Fight Club: Doctors v. Lawyers, Chicago Medicine, June 2012, at 8 (cover story).

Fight Club: Doctors v. Lawyers, Chicago Medicine, June 2012, at 8 (cover story).

This article, a shorter version of an article first published in the Temple Law Review, argues that doctors and lawyers have strong shared self-interests that should motivate them to improve their bitter relations, while offering several specific examples of ways to accomplish that goal.

Among other things, the article traces the history of medical malpractice litigation in the U.S. Did you know that the first reported medical malpractice case occurred in 1794 and that lawyers were first called sharks by doctors in 1878? Here’s an excerpt:

Relations between doctors and lawyers got off to a rocky start in the first reported U.S. medical malpractice case, Cross v. Guthery, decided by a Connecticut court in 1794. The defendant operated on the plaintiff’s wife to remove a breast. She died three hours after the surgery because, according to the court, the defendant “performed said operation in the most unskillful, ignorant and cruel manner.”

The jury awarded the plaintiff £40. One can imagine relations got frosty in the litigation when the defendant doctor asserted that the plaintiff wasn’t entitled to damages because he allegedly had agreed to settle the case for £15—which the doctor claimed the plaintiff owed him “for doctoring his wife.” The court rejected the defense and ruled for the plaintiff.

Medical malpractice lawsuits were rare when Cross was decided. Early on, some physicians actually embraced malpractice litigation as a way to cleanse their ranks of quacks and charlatans. At the time of the American Revolution, only 5 percent of the nation’s 3,500 medical practitioners had any type of medical degree. Relations soured, however, with a surge of lawsuits filed between 1840-50, a period denoted by James Mohr as the nation’s first “medical malpractice crisis.”

By 1860, a book review of an early treatise about medico-legal jurisprudence opined that “law and medicine had evolved into mutually incompatible professions.” Less restrained assessments of the relationship were abundant. As Mohr noted, “[i]t would be easy to fill several hundred pages full of vituperative, anti-legal rhetoric from medical journals after mid-century.”

The first reported unflattering comparison by doctors of lawyers to a certain ocean predator appeared around this time. In 1878 physician Eugene Sanger wrote that medical malpractice lawyers “follow us as the shark does the emigrant ship.” The epithet has enjoyed impressive staying power. A hundred years later, the president of the Association of American Medical Colleges told a graduating medical school class, “We’re swimming in shark-infested waters where the sharks are lawyers.”

The article argues that the two professions have a stronger self-interest in building up professions generally than in continuing to tear each other down.

Leave a Reply