February 10th, 2012 What is it about Texas federal district court judges named “Sam” that makes them so ornery? First, we had the notorious U.S. District Judge Samuel Kent from San Antonio (see here, here, here, and here). Now U.S. District Judge Samuel Sparks from Austin (see here and here) comes along to fill the void.

Regrettably, while most law schools do a good job screening and training students, some students manage to graduate from and pass state bar exams who lack competent skills. Not knowing the actors, we have no basis for arguing with Judge Sparks’ evaluation of the lawyer named (we left him unnamed) in the order below, but bludgeoning him so harshly in a permanent public record seems over the top (some paragraph breaks inserted):

The Court has already turned down two extremely tempting offers to transform this case from a boring old federal lawsuit into an exciting, politically-charged media circus. As any competent attorney could have predicted, the Court declines the latest invitation as well.

However, the Court is forced to conclude [name omitted], the attorney whose signature appears on this motion, is anything but competent. A competent attorney would not have filed this motion in the first place; if he did, he certainly would not have attached exhibits that are both highly prejudicial and legally irrelevant; and if he foolishly did both things, he surely would not be so unprofessional as to file such exhibits unsealed.

A competent attorney who did those things would be deliberately disrespecting this Court and knowingly shirking his professional responsibilities, offenses for which he would be lucky to retain his bar card, much less an intact bank balance.

For [name omitted]’s sake, and because the Court has no time to hold a sanctions hearing—in part because it must take time out of deciding the actual legal issues in this case to address the self-serving entreaties of attention-seekers like [name omitted]—the Court assumes [name omitted] is as incompetent as he appears. Rather than sanction him, the Court simply does what [name omitted] would have done if he was a competent professional, and seals attachment 7 to his motion.

I have no problem with judges dressing down lawyers in a very direct way when they deserve it. In fact, I wish more judges would do it. But putting such a personal attack in a written order that will last forever may not be the best way to go.

–Order, Texas Medical Providers Performing Abortion Services v. Lakey, Case No. A-11-Ca-486-S (W.D. Tex., Aug. 22, 2011). Thanks to Gaspar Forteza.

December 29th, 2011  Expert's testimony had more holes in it than this guy. In December 2011, the U.S. Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, per Judge Richard Posner, reversed a jury verdict in favor of an airline against Fed Ex for $65,998,411, the precise amount the airline had requested in damages.

One issue was the admissibility of complex testimony regarding the damages calculations by the airline’s expert witness, a forensic accountant named Morriss. Posner was not impressed by the expert’s regression analysis testimony:

Morriss’s regression had as many bloody wounds as Julius Caesar when he was stabbed 23 times by the Roman Senators led by Brutus. We have gone on at such length about the deficiencies of the regression analysis in order to remind district judges that, painful as it may be, it is their responsibility to screen expert testimony, however technical; we have suggested aids to the discharge of that responsibility. The responsibility is especially great in a jury trial, since jurors on average have an even lower comfort level with technical evidence than judges. The examination and cross-examination of Morriss were perfunctory and must have struck most, maybe all, of the jurors as gibberish. It became apparent at the oral argument of the appeal that even ATA’s lawyer did not understand Morriss’s analysis; he could not answer our questions about it but could only refer us to Morriss’s testimony.

Posner continued, saying: “If a party’s lawyer cannot understand the testimony of the party’s own expert, the testimony should be withheld from the jury. Evidence unintelligible to the trier or triers of fact has no place in a trial.” Posner suggested the reason the jurors returned a verdict for the exact amount, to the penny, that the airline sought was because they had no clue how to compute the damages.

That all makes perfect sense, but I feel for both the trial judge and the airline’s lawyer–and, of course, the jurors.

Trial judges are required to prescreen expert testimony for reliability, but that’s often practically impossible in highly technical areas such as engineering, medicine, and, in this case, regression analyses. The lawyers aren’t in much better of a position.

Judges and lawyers are smart and have well-developed critical-thinking skills, but those qualities don’t enable them to magically master bodies of technical knowledge in which they have no training. Many scholars have proposed enlisting expert judges and juries in technical, complex cases.

Of course, in the end, Posner was right. If an expert can’t explain how he how arrived at his conclusions in a way that laypersons–including judges and lawyers–can understand, the testimony should be excluded.

—ATA Airlines, Inc. v. Federal Express Corp., Case Nos. 11-1382, 11-1492, 7th Cir., Dec. 27, 2011. Thanks to Larry Buser.

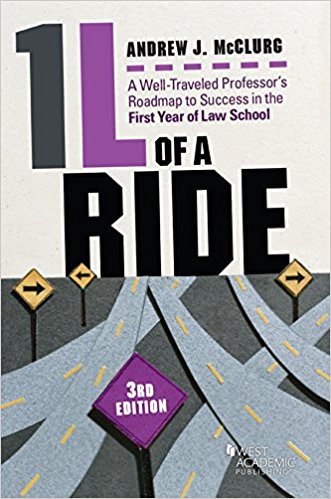

December 10th, 2011 U.S. District Judge Sam Sparks down in Austin, TX, peeved by the conduct of the lawyers in a pending case, chastised them for being “unable to practice law at the level of a first year law student” and ordering them to attend a kindergarten party at the courthouse. Here are the pertinent parts of his order:

You are invited to a kindergarten party … in Courtroom 2 of the United States Courthouse, … Austin, Texas.

The party will feature many exciting and informative lessons, including:

• How to telephone and communicate with a lawyer

• How to enter into reasonable agreements about deposition dates

• How to limit depositions to reasonable subject matter

• Why it is neither cute nor clever to attempt to quash a subpoena for technical failures of service when notice is reasonably given; and

• An advanced seminar on not wasting the time of a busy federal judge and his staff because you are unable to practice law at the level of a first year law student.

Invitation to this exclusive event is not RSVP. Please remember to bring a sack lunch! The United States Marshals have beds available if necessary, so you may wish to bring a toothbrush in case the party runs late.

This is the second time Judge Sparks has berated lawyers regarding their kindergarten skill-set.

Sparks’ boss, U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Edith Jones, was not amused by the “cute” order. Abovethelaw.com, via the Texas Lawyer, reported an email from Judge Jones to Judge Sparks that said in part:

It has not escaped my attention, or that of my colleagues or, I am told, nationally known blog sites that you have issued several ‘cute’ orders in the past few weeks. The order attached below is the most recent.

Frankly, this kind of rhetoric is not funny. In fact, it is so caustic, demeaning, and gratuitous that it casts more disrespect on the judiciary than on the now-besmirched reputation of the counsel. It suggests either that the judge is simply indulging himself at the expense of counsel or that he is fighting with counsel in what, as Judge Gee used to say, is surely not a fair contest. It suggests bias against counsel.

Guess we won’t be seeing any Sparks flying in Texas for a while.

— Order, Morris v. Coker, Case Nos. A-ll-MC-712-SS, A-ll-MC-713-SS, A-ll-MC-714-SS, A-ll-MC-7IS-SS, W.D. Tex., Aug. 26, 2011. Thanks to Professor Jodi Wilson, Douglas Giuliano, and others.

November 27th, 2011 You know a judicial document is going to be a great read when it is captioned:

Order Denying MAAF’s Motion to Preclude the French Phrase ”Quel Jeu Doit-on Jouer Vis-à-vis des Autorités de Californie?” From Being Translated as “What Game Must We Play With the California Authorities?”

This opinion from U.S. District Judge A. Howard Matz (C.D. Cal.) stemmed from the judge’s frustration in overseeing a series of over-litigated lawsuits arising from the collapse of a California insurance company. The motion giving rise to the order, after all, was the twentieth motion in limine the judge had addressed in recent days.

Judge Matz seemed irritated that “some of the French litigants caught up in these complicated cases are still coping with the ‘mystifying’ peculiarities of American courts. They appear to assume, for example, that no judge is capable of using common sense (and perhaps some pre-existing familiarity with French) to understand a straightforward French phrase.”

The motion turned on the meaning of the French word “jeu” in a document addressed to one of the French defendants. The document posed a question: “Quel jeu doit-on jouer vis-à-vis des autorités de Californie?” The California Insurance Commissioner’s expert asserted the question translates to: “What game must we play with the California authorities?” The defendant’s expert claimed it means: “What approach must we take with the California authorities?”

Judge Matz accused the defendant’s expert of playing games with the court (paragraph breaks inserted):

If M. Simonet [composer of the document] was not speaking about a “game,” surely Ms. Zarelli [defendant’s expert translator] is playing one. The problems with her declaration are abundant. First, she relies only on a French-to-French dictionary. Wouldn’t the fairest, most reliable way to ascertain the correct English meaning of “jeu,” as M. Simonet used it, be to consult a French to English dictionary?

That’s what the Commissioner’s expert translator does: she points to Harrap’s Shorter Dictionnaire. . . . And what does that more reliable source reveal? Zut alors! Of the many definitions and examples of how “jouer” and “jeu” are translated, almost all are perfectly consistent with how “jeu” was translated in the document that MAAF seeks to keep out: as a “game,” and often with a connotation of “trickery.” Harrap’s even translates “jouer le jeu” as “to play the game.” It translates other examples of the use of “jeu” into such familiar, straightforward English words andphrases as “all this fooling around;” “what’s your game?;” “to play into one’shands . . ..”

Moreover, as the Commissioner’s language expert points out, the definition that Ms. Zarelli happened to choose — “manière d! agir” — includes, if one bothers to take the complete entry into account, which Ms. Zarelli did not do — “manège” and “stratagème.” The connotations of those terms are hardly helpful to MAAF; they mean “ploy” or “trick.” In short, both the literal meaning and the context in which M. Simonet asked his not-so-rhetorical question “Quel jeu doit- on jouer vis-à-vis des autorités de Californie?” is entirely consistent with “What game must we play with the California authorities?”

Judge Matz must have been enjoying himself by this point because he added a closing footnote comparing the bravery and last name of the plaintiff’s lawyer—one “Ney”—to “Ney, the Duc d’Elchingen and Prince de la Moskova,” an army commander who Napoleon once called “the bravest of the brave.”

What did the lawyer do that was so brave? He had the nerve (“considerable fortitude,” as Matz put it) to file what the judge considered to be a ridiculous motion.

— Garamendi v. Altus Fin. S.A., Case No. CV-99-2829 (CWx) (C.D. Cal, Feb. 10, 2005). Thanks to Michael Barclay

November 27th, 2011  When one is not enough. Wait. That’s not right. It’s Judge Jacob Hart of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. Can’t be too careful about those typos. Just ask the plaintiff’s lawyer in Devore v. City of Philadelphia.

Judge Hart reduced his attorney’s fee award by $60,000 based on the poor quality of his written work, which, according to the judge, was “careless to the point of disrespectful.” The defendants described it even less charitably, as “vague, ambiguous, unintelligible, verbose and repetitive.” And those were the things they liked about it. Kidding.

The court noted that throughout the litigation, counsel identified the court as: “THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTER [sic] DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA,” adding that “[c]onsidering the religious persuasion of the presiding officer, the ‘Passover District’ would have been more appropriate.”

The priceless part (and what elevated the case into the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame) was the lawyer’s written response to the assertion that his fees should be reduced because of typos:

As for there being typos, yes there have been typos, but these errors have not detracted from the arguments or results, and the rule in this case was a victory for Mr. Devore. Further, had the Defendants not tired [sic] to paper Plaintiff’s counsel to death, some type [sic] would not have occurred. Furthermore, there have been omissions by Defendants, thus they should not case [sic] stones.

Judge Hart said that the above errors would have been “brilliant” if intentional, but that, based on the lawyer’s filings, “we know otherwise.”

Concluding that the lawyer’s filings wasted a lot of the court’s and the defendants’ time, the court halved the lawyer’s requested hourly rate from $300 per hour to $150. Non-lawyers might consider it amusing that a lawyer whose work is so poor that the court publicly disses him could still earn $150 an hour, but to be fair to the lawyer, he obtained a good result in the case for his clients. Also, the judge commended him for his in-court work.

May this case be a lesson to all law students out there who discount the value of their legal writing courses, not to mention their eighth-grade English courses. Cheers for Judge Hurt.

— Devore v. City of Philadelphia, No. 00-3598, 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 3635, at *7–8 (E.D. Pa., Feb. 20, 2004). Thanks to Cynthia Cohan and Professor Howard Wasserman.

November 27th, 2011 The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure permit any electronic document to be e-filed until midnight on the due date. Microsoft electronically filed a motion for summary judgment 4 minutes and 27 seconds late on the night of June 26, 2003.

Microsoft’s adversary in the litigation, Hyperphase Technologies, Inc., incensed by this grievous rule breach, filed a motion to strike the motion for summary judgment as untimely.

U.S. Magistrate Stephen L. Crocker, clearly annoyed, blessed us with this sarcastic order:

In a scandalous affront to this court’s deadlines, Microsoft did not file its summary judgment motion until 12:04:27 a.m. … I don’t know this personally because I was home sleeping, but that’s what the court’s computer docketing program says, so I’ll accept it as true.

Microsoft’s insouciance so flustered Hyperphase that nine of its attorneys [names omitted] promptly filed a motion to strike …. Counsel used bolded italics to make their point, a clear sign of grievous inequity by one’s foe. True, this court did enter an order … ordering the parties not to flyspeck each other, but how could such an order apply to a motion filed almost five minutes later? Microsoft’s temerity was nothing short of a frontal assault on the precept of punctuality so cherished by and vital to this court.

Wounded though this court may be by Microsoft’s four minute and twenty-seven second dereliction in duty, it will transcend the affront and forgive the tardiness. Indeed, to demonstrate the evenhandedness of its magnanimity, the court will allow Hyperphase on some future occasion in this case to e-file a motion four minutes and thirty seconds late ….

— Hyperphrase Techs., Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 56 Fed. R. Serv. 3d (Callaghan) 467 (W.D. Wis. 2003). Thanks to Cynthia Cohan.

November 24th, 2011 Judge Mark Painter, Ohio First District Court of Appeals, took some lawyers to task for moving to strike their opponent’s appellate brief for exceeding the page limitations set by rule, apparently even redrafting portions of the brief in the process:

Not wishing to let stand a brief they consider too long, counsel for appellant … have moved this court to strike [appellees’ brief] … contending the brief (1) put the citations in footnotes (where they belong!); and (2) uses footnotes to “get around” the page limit. And counsel even goes so far as to redraft their opponent’s brief, inserting the jumble of letters and numbers into the paragraphs—even the references to the record. Thus bollixed up and unreadable, the brief comes out to 38.5 pages, instead of the regulation 35. Egad. …

Our dreary day has been enlivened by the thought that lawyers care about one another’s prose so much as to redraft it. And that this dispute is so close that it may turn on a few extra pages of a lawyer’s argument. We can’t wait to read the final version—or maybe we should wait for the movie.

As to citations, they belong in footnotes. Putting goofy letters and numbers in the middle of paragraphs destroys readability. We had to do that with typewriters, just as we had to use underlining because typewriters did not have italics. No more.

Judge Painter did agree with the objectors that the other side shouldn’t have used so many speaking footnotes. He “venture[d] a guess that this court’s eventual opinion resolving this dispute will be fewer than 20 pages,” and suggested to both sides that “less is usually more” when it comes to legal drafting.

— M&M Metals Int’l, Inc. v. Continental Casualty Co., 870 N.E.2d 167, 167 (Ohio Ct. App. 2006).

November 22nd, 2011  One-third of the way toward resolving lawyer disputes. Fed up with wrangling lawyers, U.S. District Judge Gregory A. Presnell (M.D. Fla.) came up with a novel dispute resolution procedure: the game of “rock, paper, scissors.”

In what Judge Presnell called “the latest in a series of Gordian knots that the parties have been unable to untangle” without court assistance, the parties were unable to agree on a location for a deposition.

The judge directed the lawyers to convene at a neutral site, and if they couldn’t agree on even that much, to meet on the steps of the federal courthouse. He further instructed that:

Each lawyer shall be entitled to be accompanied by one paralegal who shall act as an attendant and witness. At that time and location, counsel shall engage in one (1) game of “rock, paper, scissors.” The winner of this engagement shall be entitled to select the location for the 30(b)(6) deposition ….

Actually, rock, paper, scissors resolutions are anything but novel. Although there are competing theories of the origin of the game, according to Wikipedia, the Chinese invented during the Ming dynasty, where warlords allegedly played a similar contest called shoushiling, which can be translated to “hand-command.” The warloads used the game to decide, among other things, where depositions would be held and whose head would get cut off.

So who won? It might not matter. Rumor has it the appeal will be decided by eeny, meeny, miny, moe.

— Avista Mgmt., Inc. v. Wausau Underwriters Ins. Co., Case No. 6:05-cv-1430-Orl-31JGG, 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 38526 (M.D. Fla., June 6, 2006). Thanks to Brian Abramson and Jeff James.

November 20th, 2011  Don't know much about history. In a convoluted libel case, the defendant, a lawyer, argued on appeal that the plaintiff’s counsel delivered a prejudicial, inflammatory closing argument.

But the bigger problem was that his historically based closing argument—which invoked Jesus Christ, Julius Caesar, the Philistines and Mennonites—was off on the facts. Here’s an excerpt:

You may remember when Christ was preaching the gospel, in the Holy Roman Empire that Julius Caesar was Emperor of Rome. As Christ was making his way toward Rome, the Mennonites and the Philistines stopped him in the road and they sought to entrap him. They asked Christ: ‘Shall we continue to pay tribute unto Caesar?’ And you will remember, in the Book of St. Matthew it is written that Christ said: ‘Render ye unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and unto God the things that are God’s.

Inspiring perhaps, but the lawyer made a few teensy-weensy historical errors. His timeline, for example, was a off a little. Okay, a lot. Six to eight centuries. The court pointed out the faux pas:

The Holy Roman Empire did not come into existence until about 800 years after Christ. Julius Caesar, who was never Emperor of Rome, was dead before Christ was born. Christ was never on His way to Rome and the Philistines had disappeared from Palestine before the birth of Christ. The Mennonites are a devout Protestant sect that arose in the Sixteenth Century A.D.

Some good news for the lawyer though. The judge was impressed he could cram so much misinformation into one short excerpt. As the judge said it, the argument excerpt “is noteworthy only because of the ease with which the speaker crowded into one short paragraph such an abundance of misinformation.”

Give him credit for that. If the lawyering thing doesn’t work out, he could go to work for a cable news network.

— Hall v. Brookshire, 285 S.W.2d 60, 66–67 (Mo. Ct. App. 1955). Thanks to Judge James Barlow.

November 20th, 2011  U.S. District Judge Sam Sparks does not enjoy lawyers he perceives as having kindergarten skill-sets. In 2011, U.S. District Judge Sam Sparks, Western District of Texas, got in trouble with his bosses at the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals for ordering the lawyers in a case to attend a kindergarten party. It wasn’t the first time Judge Sparks used kindergarten references to berate lawyers.

In a 2004 case called Klein-Becker, LLC v. Stanley, Judge Sparks expressed his “disgust” with squabbling among the lawyers in a barrage that began with his expressing doubt as to whether the lawyers had ever attended kindergarten and ended by telling him them to “get a life” (some paragraph breaks inserted):

When the undersigned accepted the appointment from the President of the United States of the position now held, he was read to face the daily practice of law in federal courts with presumably competent lawyers. No one warned the undersigned that in many instances his responsibility would be the same as a person who supervised kindergarten.

Frankly, the undersigned would guess the lawyers in this case did not attend kindergarten as they never learned how to get along well with others. Notwithstanding the history of filings and antagonistic motions full of personal insults and requiring multiple discovery hearings, earning the disgust of the this Court, the lawyers continue ad infinitum.

[Court recounts current dispute in which, despite the court’s order allowing a pleading to be filed on July 23, 2004, defendants’ counsel filed a motion for reconsideration, claiming the pleading should have been filed July 19.]

The Court simply wants to scream to these lawyers, “Get a life” or “Do you have any other cases?” or “When is the last time you registered for anger management classes?”

Neither the world’s problems nor this case will be determined by a … [pleading] which is four days later, even with the approval of the presiding judge.

If the lawyers in this case do not change, immediately, their manner of practice and start conducting themselves as competent to practice in the federal court, the Court will contemplate and may enter an order requiring the parties to obtain new counsel.

Judge Sparks wrapped up by saying that if it wasn’t already clear from the tone of the order, the motion for reconsideration was denied. Hmm, I think he was pretty clear.

— Klein-Becker, LLC v. Stanley, Case No. A-03-CA-871-SS, 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 19107, at *4–6 (W.D. Tex. July 21, 2004). Thanks to Michael Barclay.

November 18th, 2011 Several grounds exist for a judge denying a lawyer’s motion. Now we have a new one: incomprehensibility.

Displeased with a lawyer’s inartful motion-drafting, U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Leif M. Clark (W.D. Tex.) entered an order captioned “Order Denying Motion for Incomprehensibility.” The judge couldn’t figure out what the heck the defendant was requesting in a motion titled, “Defendant’s Motion to Discharge Response to Plaintiff’s Response to Defendant’s Response Opposing Objection to Discharge.”

Judge Clark said: “The court cannot determine the substance, in any, of the Defendant’s legal argument, nor can the court even ascertain the relief that the Defendant is requesting. The Defendant’s motion is accordingly denied for being incomprehensible.”

Perhaps worried that the defendant might miss his point, Judge Clark appended a footnote in which he invoked the following quotation from the Adam Sandler movie, Billy Madison:

Mr. Madison [Sandler’s character], what you’ve just said is one of the most insanely idiotic things I’ve ever heard. At no point in your rambling, incoherent response was there anything that could even be considered a rational thought. Everyone in this room is now dumber for having listened to it. I award you no point, and may God have mercy on your soul.

— Order Denying Motion for Incomprehensibility, In re King, Case No. 05-56485-C, Feb. 21, 2006. Thanks to Sharee Moser.

November 16th, 2011 U.S. District Judge Richard P. Matsch awarded attorneys’ fees and costs in a patent infringement case against a pair of high-echelon lawyers and their clients for trial misconduct “reflecting an attitude of ‘what can I get away with?’” and a “winning is all that is important approach” to litigation. A media report estimated the fees and costs could run several million dollars. Judge Matsch had previously thrown out the plaintiffs’ $51 million verdict in the case based on the same conduct.

The case raises interesting questions about the extent of a judge’s obligation to control attorney conduct it finds objectionable during the course of a trial.

The facts are complicated and readers interested in the full story should consult the judge’s order. But basically, the judge was ticked off that the plaintiffs’ lawyers pursued a trial strategy that the judge considered legally untenable, including attempting to establish a patent infringement by showing substantial similarity between the plaintiffs’ product and the defendants’ product.

Judge Matsch opined (paragraph breaks inserted):

Upon reflection, this Court finds and concludes that the rulings on the claims construction issues adjudicated the fairly debatable issues in this case and that the manner in which plaintiffs’ counsel continued the prosecution of the claims through trial was in disregard of their obligations as officers of the court.

The fairness of the adversary system of adjudication depends upon the assumption that trial lawyers will temper zealous advocacy of their client’s cause with an objective assessment of its merit and be candid in presenting it to the court and to opposing counsel.

When that assumption has been contradicted by a trial record of conduct reflecting a winning is all that is important approach to the trial process, the court has a duty to redress this resulting harm to the opposing party.

Judge Matsch essentially took the position that the plaintiffs’ claims were frivolous. However, he had previously denied the defendants’ motion for summary judgment and the jury returned a verdict in the plaintiffs’ favor. Defendants argued that these events showed the claims had merit, but the judge disagreed.

Perhaps most interesting was the defendants’ argument that if the judge found the trial conduct to be objectionable, he should have done something about it during the trial. In the judge’s words, the plaintiff’s lawyers “argue that they should not be held responsible for what they were able to get away with during the trial presentation.”

The argument does carry some persuasive force, particularly since the judge apparently denied objections by defendants’ counsel to some of the misconduct.

But Judge Matsch took the position that counsel were already aware of the court’s admonitions regarding the trial strategy, so he didn’t have any obligation to restrain it during the trial.

— Medtronic Navigation, Inc. v. Brainlab Medizinische Computersystems GMBH, No. 98-cv-01072-RPM, 2008 WL 410413 (D. Colo. 2008).

November 15th, 2011 Most “funny” judicial opinions aren’t ha-ha funny. They’re merely amusing or interesting. But Lawhaha.com’s scientific focus group tests showed that the colloquy below between the chastised lawyer and the judge makes people laugh out loud. For that, it’s in the SJO Hall of Fame.

In Ahmed v. Reiss Steamship Co., a federal judge held the plaintiff’s lawyer in contempt of court for failure to appear for trial. Judge Ann Aldrich (N.D. Ohio) was disturbed that the lawyer had “told two different federal district court judges that he was appearing before the other,” sort of the legal version of the old childhood stratagem for a night out in which each kid tells his parents he’s spending the night at the other’s house.

Things turned bizarre when the lawyer finally decided to explain his absence, in a way the court found to be “lacking taste and any respect for courtroom decorum”:

MR. JAQUES: I wasn’t here because I couldn’t be here. I was not here, Judge, because I had the screaming itches in the crotch. I was so badly in need of medical care that I had been in communication with my physician a lot. Judge, I wasn’t here because I would have been scratching my testicles constantly if I had been here. Judge–

THE COURT: Mr. Jaques–

MR. JAQUES: Judge, do you understand that?

THE COURT: You don’t have to be so graphic. You could have simply let the Court know that for medical reasons you were not going to be here and you could have–

MR. JAQUES: Judge, it was not a medical reason that I would have been able to frame earlier. That’s one thing.

THE COURT: It doesn’t seem awfully difficult to me. Is there anything else?

The lawyer submitted a letter from his doctor to bolster his claim:

It has been recommendation (sic) … that because of the nature, location and symptoms of this ailment he should avoid to be in public places and mainly court appearances all of which could jeopardize his professional appearance …

While the judge did not “question the intensity of [the lawyer’s] discomfort,” she held him in contempt for not notifying the court of the problem and for representing that he couldn’t attend trial because he was appearing before another judge.

— Ahmed v. Reiss S.S. Co., 580 F. Supp. 737, 742 (N.D. Ohio 1984). Thanks to Michael Slodov.

November 13th, 2011 It’s actually pretty hard to get disbarred as a lawyer, as opposed to reprimanded or suspended, maybe harder than it should be. But with enough effort, it can be done, as shown in a 2010 case where the Kansas Supreme Court disbarred a lawyer after what it called repeated episodes “of rude, disruptive, and at times criminal, misconduct.”

According to the court’s findings (the lawyer disputed the facts), these incidents included:

1. Yelling at a court clerk to tell a prosecutor “to get his ‘ass’ in the courtroom,” telling the clerk he was smarter than anyone in the clerk’s office, and telling all the clerks present that they were “f****** b******.”

2. Getting in a physical altercation with a Deputy Marshal at the federal courthouse after he refused to obey commands to return to the security entrance after setting off the magnetometer, for which the lawyer was subsequently indicted and convicted.

3. Repeatedly talking loudly and abusively to the judge in a Missouri case, saying, among other things: “that the proceeding was a ‘joke’ and a ‘travesty’”; accusing the judge of “apparent reckless, bias, [and] prejudice”; telling the judge that the “proceeding was a joke”; accusing the court of “corrupting and stinking up the case” and “corrupting the system”; accusing the court of “being anything but impartial, justiciable, and anything but incompetent”; wadding up a copy of a pleading filed by opposing counsel, throwing it to the floor, and grinding it into the floor with his shoe; and stating to the court that “you’re going to sit up there with the audacity and the smugness of your holiness.” For these acts, he was held in contempt of court.

4. Changing a previously agreed on fee agreement from a $3,500 flat fee to an hourly rate of $3,500.

5. Getting into an argument with a court bailiff in another case, as a result of which he was held in contempt of court. Among other conduct, he accused the court of being a “kangaroo court” and said that “all you guys in Grandview [Missouri] are all snakes, that’s all you all are.” The bailiff reported that during this fracas, the lawyer’s client was overheard saying “That’s my attorney and I don’t want to have anything to do with him.”

— In re Romious, 240 P.3d 945, 947 (Kan. 2010). Thanks to Doug Cressler.

November 6th, 2011  Appellate court doesn't like drug agents talking like this guy. In suppressing evidence in a drug case, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit had some harsh words for the federal drug agents who were involved. The Court also did not take kindly to the trial judge threatening to put one of the lawyers in jail for failing to answer phone calls from the court reporter about a disputed bill.

But first, the court’s indictment of Dragnet-ese. The court did not like the way the drug agents talked, as it explained in a footnote (paragraph breaks inserted):

1. The agents involved speak an almost impenetrable jargon. They do not get into their cars; they enter official government vehicles. They do not get out of or leave their cars, they exit them. They do not go somewhere; they proceed. They do not go to a particular place; they proceed to its vicinity. They do not watch or look; they surveille. They never see anything; they observe it. No one tells them anything; they are advised.

A person does not tell them his name; he identifies himself. A person does not say something; he indicates. They do not listen to a telephone conversation; they monitor it. People telephoning to each other do not say “hello;” they exchange greetings. An agent does not hand money to an informer to make a buy; he advances previously recorded official government funds.

To an agent, a list of serial numbers does not list serial numbers, it depicts Federal Reserve Notes. An agent does not say what an exhibit is; he says that it purports to be. The agents preface answers to simple and direct questions with “to my knowledge.” They cannot describe a conversation by saying “he said” and “I said;” they speak in conclusions. Sometimes it takes the combined efforts of counsel and the judge to get them to state who said what.

Under cross-examination, they seem unable to give a direct answer to a question; they either spout conclusions or do not understand. This often gives the prosecutor, under the guise of an objection, an opportunity to suggest an answer, which is then obligingly given.

As a side issue, the opinion contains a lengthy discussion of an incident in which the trial judge humiliated one of the defense lawyers in court and threatened to send him to jail for raising questions about the court reporter’s fee. The court reporter, who charged by the page, indented the text on each page so it began in the middle of the page, used only 25 lines of type per page instead of the standard 28, and used a font that was larger than normal. The lawyer tried to present an affidavit establishing that the transcript was twice as long as it needed to be, and thus twice as costly. The judge’s response? Here’s a snippet:

MR. LANGER (defense counsel): You say you spoke to me?

THE REPORTER: No. [TO JUDGE:] He wouldn’t even answer my phone calls.

MR. LANGER: Your Honor–

THE COURT: I know it. That is another thing. I ought to throw you in jail for not doing that, for not answering the phone calls of the reporter.

The Ninth Circuit disapproved of the trial judge’s conduct.

— United States v. Marshall, 488 F.2d 1169, 1171 n.1, 1200 (9th Cir. 1973). Thanks to Frank Zotter.

October 31st, 2011 Before his flame-out, Judge Samuel Kent in Galveston, Texas, garnered a lot of attention for his abrasive writing style. Opinion was split in the legal community. Examples are here, here, here and here.

Some lawyers considered his sarcastic, often rude and insulting opinions hilarious. Some considered them very unjudicial and inappropriate. Probably many others viewed them as a combination of both.

Professor Steven Lubet of Northwestern University law school weighed in on the issue with a piece called “Bullying from the Bench,” in The Green Bag. Steve took issue with Kent’s humor, particularly his ad hominem attacks on lawyers. Here’s a brief excerpt:

Federal judges exercise enormous power over lawyers and their clients. Armed with life tenure and broad discretion, a judge can do great damage to an attorney’s reputation and career, while the lawyer has almost no recourse. So when Judge Kent decided to torment the hapless counsel in the Bradshaw case are identified by name in the published opinion—he was taking aim at people who could not defend themselves. …

In litigation, the judge is the maximum boss. Everyone else is a supplicant, compelled to engage in stylized demonstrations of obedience. We stand when the judge enters and leaves the room. Our “pleadings” are “respectfully submitted.” Before speaking, we make sure that it “pleases the court.” We obey the judge’s orders and we even say “thank you” for adverse rulings. …

By belittling the lawyers who appear before him, Judge Kent used his authority to humiliate people who—in the courtroom environment—are comparatively helpless. There is a name for that sort of behavior, and it isn’t adjudication. It’s bullying.

Steven got it right, of course. The relationship between judge and lawyers is about as one-sided as it gets. The judge holds all the cards. Sometimes lawyers deserve to get chewed out, but Kent was over the top.

— Steven Lubet, Bullying from the Bench, 5 Green Bag 2d 11, 12 (2001).

October 31st, 2011 Another ad hominem-laced love letter to lawyers from former U.S. District Judge Samuel Kent, Galveston, TX. This one was a maritime personal injury case in which defense counsel moved for summary judgment on behalf of his client Phillips Petroleum.

Note that, in insulting the lawyers throughout, Judge Kent emphasized that the lawyers for both sides were “likeable” and that he had “affection” for them:

[Judge Kent begins the order by stating the case, then proceeds as follows.]

[T]he Court notes that this case involves two extremely likable lawyers, who have together delivered some of the most amateurish pleadings ever to cross the hallowed causeway into Galveston, an effort which leads the Court to surmise but one plausible explanation. Both attorneys have obviously entered into a secret pact—complete with hats, handshakes and cryptic words—to draft their pleadings entirely in crayon on the back sides of gravy-stained paper place mats, in the hope that the Court would be so charmed by their child-like efforts that their utter dearth of legal authorities in their briefing would go unnoticed.

Whatever actually occurred, the Court is now faced with the daunting task of deciphering their submissions. With Big Chief tablet readied, thick black pencil in hand, and a devil-may-care laugh in the face of death, life on the razor’s edge sense of exhilaration, the Court begins.

[The court discusses summary judgment law, followed by several caustic remarks about the quality of defense counsel’s (representing Phillips) filings, including the statement that “[a] more bumbling approach is difficult to conceive.” Then the court tears into plaintiff’s counsel.]

Plaintiff responds to this deft, yet minimalist analytical wizardry with an equally gossamer wisp of an argument, although Plaintiff does at least cite the federal limitations provision applicable to maritime tort claims. … Naturally, Plaintiff also neglects to provide any analysis whatsoever of why his claim versus Defendant Phillips is a maritime action. Instead, Plaintiff “cites” to a single case from the Fourth Circuit.

Plaintiff’s citation, however, points to a nonexistent Volume “1886” of the Federal Reporter Third Edition and neglects to provide a pinpoint citation for what, after being located, turned out to be a forty-page decision. Ultimately, to the Court’s dismay after reviewing the opinion, it stands simply for the bombshell proposition that torts committed on navigable waters … require the application of general maritime rather than state tort law … The Court cannot even begin to comprehend why this case was selected for reference. It is almost as if Plaintiff’s counsel chose the opinion by throwing long range darts at the Federal Reporter (remarkably enough hitting a nonexistent volume!). …

Despite the continued shortcomings of Plaintiff’s supplemental submission, the Court commends Plaintiff for his vastly improved choice of crayon—Brick Red is much easier on the eyes than Goldenrod, and stands out much better amidst the mustard splotched about Plaintiff’s briefing. But at the end of the day, even if you put a calico dress on it and call it Florence, a pig is still a pig. Now, alas, the Court must return to grownup land. [Court resolves issue on its own.] …

Take heed and be suitably awed, oh boys and girls—the Court was able to state the issue and its resolution in one paragraph … despite dozens of pages of gibberish from the parties to the contrary! …

After this remarkably long walk on a short legal pier, having received no useful guidance whatever from either party, the Court has endeavored, primarily based upon its affection for both counsel, but also out of its own sense of morbid curiosity, to resolve what it perceived to be the legal issue presented. Despite the waste of perfectly good crayon seen in both parties’ briefing … the Court believes it has satisfactorily resolved this matter. Defendant’s Motion for Summary Judgment is GRANTED …

— Bradshaw v. Unity Marine Corp., 147 F. Supp. 2d 668, 670–72 (S.D. Tex. 2001). Thanks to Ira Rosenau.

October 31st, 2011 Some believe the writings of impeached U.S. District Judge Samuel B. Kent, Southern District of Texas, are quite funny, but probably not many lawyers in Galveston were laughing after his June 2001 order on a motion to transfer for improper venue. Being Juge Kent, he couldn’t just deny the motion. He had to rip apart the lawyer who filed the motion:

[A]ny person with even a correspondence-course level understanding of federal practice and procedure would recognize that Defendant’s Motion is patently insipid, ludicrous and utterly unequivocally without any merit whatsoever. Worse, it is just plain blatantly wrong in light of the unambiguous language of a decades old federal statute and veritable mountains of case law addressing venue propriety.

Sound bad? It gets worse. Judge Kent went on to state that “Defendant’s obnoxiously ancient, boilerplate, inane Motion is emphatically DENIED.”

For the coup de grace, Judge Kent ended by disqualifying the lawyer from further appearing in the case “for submitting this asinine tripe.”

— Labor Force, Inc. v. Jacintoport Corp., 144 F. Supp. 2d 740 (S.D. Tex. 2001) (opinion subsequently withdrawn from bound volume).

|

Funny Law School Stories

For all its terror and tedium, law school can be a hilarious place. Everyone has a funny law school story. What’s your story?

|

Product Warning Labels

A variety of warning labels, some good, some silly and some just really odd. If you come encounter a funny or interesting product warning label, please send it along.

|

Tortland

Tortland collects interesting tort cases, warning labels, and photos of potential torts. Raise risk awareness. Play "Spot the Tort." |

Weird Patents

Think it’s really hard to get a patent? Think again.

|

Legal Oddities

From the simply curious to the downright bizarre, a collection of amusing law-related artifacts.

|

Spot the Tort

Have fun and make the world a safer place. Send in pictures of dangerous conditions you stumble upon (figuratively only, we hope) out there in Tortland.

|

Legal Education

Collecting any and all amusing tidbits related to legal education.

|

Harmless Error

McClurg's twisted legal humor column ran for more than four years

in the American Bar Association Journal.

|

|

|