June 17th, 2012  Whatever happened to “Appellant wins”? Back in 2003, in McConnell v. Federal Election Committee, the U.S. Supreme Court cleared up a major legal dispute over campaign financing. Er, well, maybe not completely cleared up.

The basic question was whether the McCain-Feingold Act, a federal statute that imposed restrictions on political contributions, violated the First Amendment free speech rights of potential contributors. A challenging issue no doubt, but certainly not too tough for the mighty U.S. Supreme Court to resolve, right?

With nine justices voting, the result could have been as simple as 8-1, 7-2, 6-3, or 5-4 in favor of one side or the other. The nine wise ones chose a slightly more complicated path. Here is the Court’s actual voting lineup straight out of the case:

STEVENS and O.CONNOR, JJ., delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to BCRA Titles I and II, in which SOUTER, GINSBURG, and BREYER, JJ., joined. REHNQUIST, C. J., delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to BCRA Titles III and IV, in which O.CONNOR, SCALIA, KENNEDY, and SOUTER, JJ., joined, in which STEVENS, GINSBURG, and BREYER, JJ., joined except with respect to BCRA § 305, and in which THOMAS, J., joined with respect to BCRA §§ 304, 305, 307, 316, 319, and 403(b). BREYER, J., delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to BCRA Title V, in which STEVENS, O.CONNOR, SOUTER, and GINSBURG, JJ., joined. SCALIA, J., filed an opinion concurring with respect to BCRA Titles III and IV, dissenting with respect to BCRA Titles I and V, and concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part with respect to BCRA Title II. THOMAS, J., filed an opinion concurring with respect to BCRA Titles III and IV, except for BCRA §§ 311 and 318, concurring in the result with respect to BCRA § 318, concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part with respect to BCRA Title II, and dissenting with respect to BCRA Titles I, V, and § 311, in which opinion SCALIA, J., joined as to Parts I, II.A, and II.B. KENNEDY, J., filed an opinion concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part with respect to BCRA Titles I and II, in which REHNQUIST, C. J.,joined, in which SCALIA, J., joined except to the extent the opinion upholds new FECA § 323(e) and BCRA § 202, and in which THOMAS, J., joined with respect to BCRA §213. REHNQUIST, C. J., filed an opinion dissenting with respect to BCRA Titles I and V, in which SCALIA and KENNEDY, JJ., joined. STEVENS, J., filed an opinion dissenting with respect to BCRA § 305, in which GINSBURG and BREYER, JJ., joined.

Who won? I have no idea.

For embodying in a single voting lineup the reason why the most accurate answer to most legal questions is “It depends,” this case gets into the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame. If members of the world’s most powerful tribunal are unable to agree on what the law means, how could one expect poor law students to do so?

— McConnell v. Federal Election Comm’n, 540 U.S. 93 (2003). Thanks to Elise Hendricks.

January 7th, 2012 A judicial friend from Florida sent along a case of first impression involving a parental rights determination between a birth mother and a biological mother that she calls “a law professor’s dream case.” It does sound a bit like a law school exam question—a very difficult one.

The case involved two women in a committed relationship who wanted to have a child. Ova from one of the women were removed, fertilized by donated sperm, and implanted in the other woman, who then gave birth to the child. Thus, one woman was the biological mother and one was the birth mother, an unusual situation to be sure.

Only the birth mother’s name appeared on the child’s birth certificate. For years, the two women reared their child together but, when the relationship failed, the birth mother, without telling the biological mother, fled to Australia with the child.

The trial court reluctantly ruled that only the birth mother was the legal mother but invited appeal of his decision. The Florida Fifth District Court of Appeal reversed, ruling that both women had parental rights to the child.

My judicial friend pointed out that this is a case begging, and no doubt destined, for scholarly attention by law professors and law students, although Judge Thomas D. Sawaya, writing for the majority, might shiver at the thought.

Judge Sawaya was not impressed that the only authority for the birth mother’s position that only gestational mothers have maternal rights were: law review articles and a Tennessee case that relied solely on a law review article.

Regarding law review articles relied on by the birth mother, the judge commented: “We do not believe that law review articles written by students and professors establish the common law.”

About the Tennessee case, Sawaya said: “The common law does not come from law students and professors who write law review articles, and we hardly think it comes from a decision rendered by a Tennessee court that does nothing more than cite a law review article as the source.”

Hmm, I guess that depends on how one defines “the common law.” The Tennessee case is part of the body of judicial precedent that forms the common law. It might not be persuasive precedent, but isn’t it still part of the common law? And simply because a judicial opinion relies on a law review article doesn’t remove the opinion from the realm of common law.

Courts cite law review articles frequently, including the U.S. Supreme Court, and there are innumerable instances of law review articles–including some written by students–that have turned the tide of the common law. As just one example, the products liability doctrine of market-share liability, first articulated by the California Supreme Court in Sindell v. Abbott Laboratories, was conceived from a student-written Note in the Fordham Law Review.

As an aside, my judge-friend was troubled that the majority’s analysis seemed to treat the child as a piece of property, giving no consideration to the best interests of the child, an issue the concurring opinion also focused on.

—T.M.H. v. D.M.T. , Case No. 5D09-3559 (Fla. 5th DCA, Dec. 23, 2011)

December 29th, 2011  Expert's testimony had more holes in it than this guy. In December 2011, the U.S. Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, per Judge Richard Posner, reversed a jury verdict in favor of an airline against Fed Ex for $65,998,411, the precise amount the airline had requested in damages.

One issue was the admissibility of complex testimony regarding the damages calculations by the airline’s expert witness, a forensic accountant named Morriss. Posner was not impressed by the expert’s regression analysis testimony:

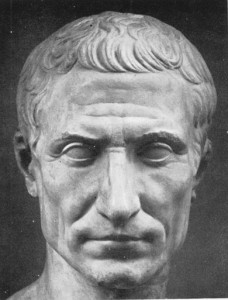

Morriss’s regression had as many bloody wounds as Julius Caesar when he was stabbed 23 times by the Roman Senators led by Brutus. We have gone on at such length about the deficiencies of the regression analysis in order to remind district judges that, painful as it may be, it is their responsibility to screen expert testimony, however technical; we have suggested aids to the discharge of that responsibility. The responsibility is especially great in a jury trial, since jurors on average have an even lower comfort level with technical evidence than judges. The examination and cross-examination of Morriss were perfunctory and must have struck most, maybe all, of the jurors as gibberish. It became apparent at the oral argument of the appeal that even ATA’s lawyer did not understand Morriss’s analysis; he could not answer our questions about it but could only refer us to Morriss’s testimony.

Posner continued, saying: “If a party’s lawyer cannot understand the testimony of the party’s own expert, the testimony should be withheld from the jury. Evidence unintelligible to the trier or triers of fact has no place in a trial.” Posner suggested the reason the jurors returned a verdict for the exact amount, to the penny, that the airline sought was because they had no clue how to compute the damages.

That all makes perfect sense, but I feel for both the trial judge and the airline’s lawyer–and, of course, the jurors.

Trial judges are required to prescreen expert testimony for reliability, but that’s often practically impossible in highly technical areas such as engineering, medicine, and, in this case, regression analyses. The lawyers aren’t in much better of a position.

Judges and lawyers are smart and have well-developed critical-thinking skills, but those qualities don’t enable them to magically master bodies of technical knowledge in which they have no training. Many scholars have proposed enlisting expert judges and juries in technical, complex cases.

Of course, in the end, Posner was right. If an expert can’t explain how he how arrived at his conclusions in a way that laypersons–including judges and lawyers–can understand, the testimony should be excluded.

—ATA Airlines, Inc. v. Federal Express Corp., Case Nos. 11-1382, 11-1492, 7th Cir., Dec. 27, 2011. Thanks to Larry Buser.

November 27th, 2011 David Cheifetz, Lawhaha’s friend from the north, sent in this Canadian court opinion about the judicial pecking order. David wrote:

Here is the pithiest and funniest summary of “stare decisis” ever written. Judge Cardozo’s explanation in “The Nature of the Judicial Process” may be the best justification and explanation, but it doesn’t hold a candle to what you’re about to read for wit and succinctness. The below summary comes from a decision by a Master of the Queens Bench of Alberta, Canada. A Master is a judge in all but name whose role is deciding preliminary motions in civil matters. The Master involved, Master Funduk, is noted for his witty judgments. The Queens Bench is the trial division of Alberta’s highest court. In the Canadian system, the highest court of any province is always the province’s Court of Appeal, even if the highest provincial trial court is called the Superior or the Supreme Court of the province. Here’s how Master Funduk summed up his role (some paragraph breaks inserted):

Any legal system which has a judicial appeals process inherently creates a pecking order for the judiciary regarding where judicial decisions stand on the legal ladder.

I am bound by decisions of Queen’s Bench judges, by decisions of the Alberta Court of Appeal and by decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada.

Very simply, Masters in Chambers of a superior trial court occupy the bottom rung of the superior courts’ judicial ladder. I do not overrule decisions of a judge of this Court.

The judicial pecking order does not permit little peckers to overrule big peckers. It is the other way around.

— South Side Woodwork (1979) Ltd. v. R.C. Contracting Ltd., [1989] A.J. No. 111, 95 A.R. 161 at 166–67 (Alta. Q.B.). Thanks to David Cheifetz.

November 21st, 2011  Simon and Garfunkel - Noted admiralty law experts. In U.S. v. McPhee, the defendants were charged with conspiracy to import marijuana, after their boat, the Notty, was intercepted by Coast Guard cutters off the coast of Florida.

A key jurisdictional issue was whether the boat was intercepted within the territorial waters of the Bahamas. Defendants argued it was, on the basis that the interdiction occurred within 12 miles of Saint Vincent Rock, which defendants asserted is a Bahamian island. The government argued that Saint Vincent Rock is only a “rock” and does not qualify as an “island.”

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit agreed with the government, although it conceded the question was not without its nuances, citing Simon & Garfunkel as authority (paragraph breaks inserted):

FN 9. The Government argued that the Notty was in international waters or on the “high seas” because “Saint Vincent Rock is a rock. If it was an island, it would be called Saint Vincent Island, not Saint Vincent Rock.” Ultimately, we must determine whether it is a rock or an island according to the statutory definitions provided by the Archipelagic Act.

We note in passing that for some purposes, the label is not altogether satisfying. Thus, for example, in the metaphysical sense, we can discern no reason why something could not be both a rock and an island at the same time.

See Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel, I am a Rock, on Sounds of Silence (Columbia 1966) (“A winter’s day, in a deep and dark December. I am alone, gazing from my window, to the streets below, on a freshly fallen silent shroud of snow. I am a rock, I am an island. I’ve built walls, a fortress deep and mighty, that none may penetrate. I have no need of friendship, friendship causes pain. It’s laughter and it’s loving I disdain. I am a rock, I am an island. Don’t talk of love. Well I’ve heard the word before. It’s sleeping in my memory. I won’t disturb the slumber of feelings that have died. If I never loved, I never would have cried. I am a rock, I am an island. I have my books and my poetry to protect me. I am shielded in my armor. Hiding in my room, safe within my womb, I touch no one and no one touches me. I am a rock, I am an island. And a rock feels no pain. And an island never cries.”).

The court did note, however, that “neither Simon nor Garfunkel has been identified as a nautical expert.”

Maybe the government could have bolstered its jurisdictional case by citing John Mellencamp and arguing that the “R.O.C.K. [was] in the U.S.A.”.

— United States v. McPhee, 336 F.3d 1269, 1279 n.9 (11th Cir. 2003). Thanks to Michael Hirschkowitz.

— See also United States v. Horn, 185 F. Supp. 2d 530, 551 n.37 (D. Md. 2002) (“She blinded me with science!”). Thanks to Kevin Cross for providing this Thomas Dolby-influenced citation in the same vein pop-music theme as McPhee, in proper Bluebook-form no less.

November 20th, 2011 A federal judge in Oklahoma, annoyed by delays in carrying out his order to commit a defendant to a medical facility, managed to maintain a perfect judicial temperament and sense of humor on hearing the news that the parties had worked out everything out on their own–without bothering to tell the judge. His “on the one hand, but on the other hand” order is a masterpiece of balance and even-handedness.

“On the one hand,” the court was grateful that the government and the defendant were able to cooperate in setting a date for the defendant to report.

“On the other hand,” the court said, “the court might be somewhat justified in experiencing annoyance at being left out of the loop in making a decision that is vested in its sound discretion. ‘Oh right, somebody better remember to tell the judge…’”

“On the one hand,” the court wanted to give due consideration to the fact that the defendant was 80 years old and was receiving treatment for a heart condition by a neurosurgeon.

“On the other hand,” the court asked, “how long may a defendant avoid imposition of justifiable court orders merely because of his age and medical condition? Where does it end? Anarchy? Dogs and cats living together?”

In the end, the court threw in the towel and agreed to let the defendant report on the date agreed to by the government. Or as the court put it: “[T]he court will be content to let imposition of its orders be held hostage by the vagaries of the schedule of some neurosurgeon in Oklahoma City.”

— Order, United States v. Stipe, Case No. 07-TP-001-RAW (E.D. Okla., May 5, 2008). Thanks to Debra Schwartz.

November 17th, 2011 You don’t have to be a famous judge or blessed with a crazy case to write a Hall of Fame Strange Judicial Opinion. Here we have a low-level New Zealand trial judge trying to educate his appellate court masters about life down in the “real world” trial court-trenches, and a good-humored, self-effacing reply from the appellate court.

In New Zealand, an appeal over a $100 fine for failure to register “a handsome German Shepherd named Ben” apparently irritated the overworked trial judge. In a memorandum, the judge sought to educate the high court about the process for administering justice in his humble court at the bottom of the judicial hierarchy:

Your honour may not be familiar with the manner in which “Minor Offences” are dealt with in this Court. Notices of Prosecution . . . are surreptitiously placed in the Judge’s “In Tray” at frequent and irritating intervals, usually in his or her absence. They come in stacks and bundles … [The trial judge proceeds to describe the variety of matters crying out for his daily attention, including applications for Massage Parlor licenses, truancy notices, underage drinking citations, etc.]

The Judge peruses the mountain of files with great care and then imposes whatever he or she deems appropriate. No hearing is held. No defendant or counsel are present. No submissions are made. No tears are shed. No howls of derision are heard from the gallery. … No anxious mother suckles a fretful child. There are no sideways glances or rolling back of eyes from counsel’s table and certainly no titters are heard to run around the Court.

The Judge sits alone in his chambers and affixes his facsimile signature to the Information Sheet perhaps muttering silent curses to himself as he does so. …

I hope this short memorandum may assist Your Honour in dealing with this appeal.

High Court Justice Grant Hammond (pretty sure this is him–please correct if wrong), chragined, contrasted the trial judge’s mundane existence with the grandeur of his much more regal appellate court, describing how on the day of the hearing over the hundred-dollar appeal, “[i]n full High Court regalia we processed bewigged and black-robed through several levels” of the court building.

It was clear Justice Hammond felt awkward about “tinkering” with the trial judge’s work. He quoted political philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s description of court systems as “a fathomless and boundless chaos, made up of fiction, tautology, technicality and inconsistency, and the administration of it a system of exquisitely contrived chicanery which maximises delay and the denial of justice.”

In the end, Hammond’s court reduced the fine to $20 because the appellant didn’t have the money to pay the higher fine.

— Lowe v. Auckland City Council (High Court, Auckland, AP44/93, 12 May 1993, Hammond, J.). Thanks to Lina Lim.

November 16th, 2011 U.S. District Judge Richard P. Matsch awarded attorneys’ fees and costs in a patent infringement case against a pair of high-echelon lawyers and their clients for trial misconduct “reflecting an attitude of ‘what can I get away with?’” and a “winning is all that is important approach” to litigation. A media report estimated the fees and costs could run several million dollars. Judge Matsch had previously thrown out the plaintiffs’ $51 million verdict in the case based on the same conduct.

The case raises interesting questions about the extent of a judge’s obligation to control attorney conduct it finds objectionable during the course of a trial.

The facts are complicated and readers interested in the full story should consult the judge’s order. But basically, the judge was ticked off that the plaintiffs’ lawyers pursued a trial strategy that the judge considered legally untenable, including attempting to establish a patent infringement by showing substantial similarity between the plaintiffs’ product and the defendants’ product.

Judge Matsch opined (paragraph breaks inserted):

Upon reflection, this Court finds and concludes that the rulings on the claims construction issues adjudicated the fairly debatable issues in this case and that the manner in which plaintiffs’ counsel continued the prosecution of the claims through trial was in disregard of their obligations as officers of the court.

The fairness of the adversary system of adjudication depends upon the assumption that trial lawyers will temper zealous advocacy of their client’s cause with an objective assessment of its merit and be candid in presenting it to the court and to opposing counsel.

When that assumption has been contradicted by a trial record of conduct reflecting a winning is all that is important approach to the trial process, the court has a duty to redress this resulting harm to the opposing party.

Judge Matsch essentially took the position that the plaintiffs’ claims were frivolous. However, he had previously denied the defendants’ motion for summary judgment and the jury returned a verdict in the plaintiffs’ favor. Defendants argued that these events showed the claims had merit, but the judge disagreed.

Perhaps most interesting was the defendants’ argument that if the judge found the trial conduct to be objectionable, he should have done something about it during the trial. In the judge’s words, the plaintiff’s lawyers “argue that they should not be held responsible for what they were able to get away with during the trial presentation.”

The argument does carry some persuasive force, particularly since the judge apparently denied objections by defendants’ counsel to some of the misconduct.

But Judge Matsch took the position that counsel were already aware of the court’s admonitions regarding the trial strategy, so he didn’t have any obligation to restrain it during the trial.

— Medtronic Navigation, Inc. v. Brainlab Medizinische Computersystems GMBH, No. 98-cv-01072-RPM, 2008 WL 410413 (D. Colo. 2008).

November 14th, 2011 The classic dilemma of the law. Which is more important: following the rules or dispensing justice? Being faithful to precedent or willing to bend technical legal rules to reach the correct result?

We struggle with these issues from the time we’re first-year law students. Rules won out in ugly fashion in In re Estate of Pavlinko.

Vasil Pavlinko and his wife, Hellen, immigrants who spoke little English, went to a lawyer to have separate wills drawn up. Both wills left their residual interest to the same person: Elias Martin, the brother of Hellen Pavlinko. Unfortunately, when it came time to sign the wills, the wills got mixed up and Vasil and Hellen each signed the other’s will.

After the couple died, Elias Martin—the sole residuary legatee under both wills—offered Vasil’s will for probate. Although conceding that the result was “unfortunate,” the Pennsylvania Supreme Court rejected Martin’s petition because Vasil had mistakenly signed Hellen’s will.

Judge Michael Angelo Musmanno, a Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Famer for his intelligent prose, dissented, in an impassioned Ode to Screwing Up:

Everyone in this case admits that a mistake was made: an honest, innocent, unambiguous, simple mistake, the innocent, drowsy mistake of a man who sleeps all day and, on awakening, accepts the sunset for the dawn.

Nothing is more common to mankind than mistakes. Volumes, even libraries have been written on mistakes: Mistakes of law and mistakes of fact. In every phase of life, mistakes occur and there are but few people who will not attempt to lend a helping hand to the person who mistakes a step for a landing and falls, or the one who mistakes a nut for a grape and chokes, or the one who steps through a glass so clear that he does not see it. This Court, however, says that it can do nothing for the victim of the mistake in this case, a mistake which was caused through no fault of his own, nor of his intended benefactors.

… I know that the law is founded on precedent and in many ways we are bound by the dead hand of the past. But even with obeisance to precedent, I still do not believe that the medicine of the law is incapable of curing the simple ailment here ….

We have said more times than there are tombstones in the cemetery where the Pavlinkos lie buried, that the primary rule to be followed in the interpretation of a will is to ascertain the intention of the testator. Can anyone go to the graves of the Pavlinkos and say that we do not know what they meant? They said in English and Carpathian that they wanted their property to go to Elias Martin.

— In re Estate of Pavlinko, 148 A. 2d 528, 532 (Pa. 1959) (Musmanno, J., dissenting). Thanks to Frank Zotter.

November 14th, 2011 In 1920, a New Jersey chancery judge was faced with a wife’s suit for marriage annulment on the ground of the husband’s alleged impotency during their five years together. The husband “vigorously protested his virility, but admitted the nonconsummation of the marriage.” The husband asserted he refrained from intercourse with his wife because he did not want to hurt her.

Interestingly, given the date, the judge thoughtfully considered whether the husband’s condition was psychological, especially since he had “submitted to an examination by one of his wife’s physicians, who testified that he was structurally a male, normal in the parts, and to all appearances capable of coition.”

The judge forged new legal ground in the U.S. by adopting from the English common law a rebuttable presumption of impotency after three years of marriage without sexual intercourse. In finding that the husband failed to overcome the presumption, the judge explained:

[T]he question comes to one of belief in his story of forbearance for five years, under most trying circumstances, simply because sexual intercourse was painful and distressing to her. I have misgivings. Such solicitude of a groom is noble, of a husband, heroic. Few have the fortitude to resist the temptations of the honeymoon. But human endurance has its limitations. When nature demands its due, youth is prodigal in the payment. Men are still cave men in the pleasures of the bed. The sex may be more temperate, but none the less passionate, and heedless of the penalty. They do not shirk the initiation nor shrink from the consequences. The husband’s plea does not inspire confidence. Common experience discredits it.

— Tompkins v. Tompkins, 111 A. 599, 601 (N.J. Ch. 1920). Thanks to Senior Judge Jim Barlow.

November 6th, 2011 The lawyer who sent in this opinion wrote that it will “make you pee in your pants laughing.” Maybe he was just caught up in the spirit of the opinion, which begins:

This case decides the heretofore undecided question of whether the act of defecating in one’s pants upon being informed of a pending criminal charge is a relevant fact for the jury.

That’s a heckuva way to get your reading audience’s attention. Here’s what happened:

The prosecutor elicited testimony from the arresting officer that, upon being informed he was under arrest for sexual child assault, the defendant defecated in his pants (although he denied doing so at trial). Defense counsel objected on relevancy grounds and the judge sustained the objection. The judge told the jury to disregard the comment. Oh yeah, I’m sure the jurors were able to just completely forget that little tidbit.

The defendant appealed, asserting a mistrial should have been granted. On appeal, the prosecutor argued that the defendant’s unseemly accident was admissible as an “excited utterance” under the rules of evidence.

“Excited utterance” is an exception to the rule the bars the introduction of hearsay testimony. Hearsay–that is, statements made outside of court–are, subject to many exceptions, barred because they are deemed untrustworthy. The basis for admitting an excited utterance into evidence is the belief that statements made under shock or surprise are likely to be trustworthy.

Judge Hardberger, writing for the Texas Court of Appeals, did an admirable job of fairly identifying the conflicting inferences that could be drawn from the alleged act by the defendant. After rejecting defendant’s argument that the act had no relevance, he wrote:

On the other hand, defecation in one’s pants upon arrest does not necessarily indicate guilt. Such an act could be evidence of the innocence of a man accused of a heinous crime he didn’t do … Granted, it could also be the act of a guilty person being found out. Or it could simply be the act of a man sick to his stomach.

The court determined that the trial judge’s instruction to the jury to disregard the testimony cured any possible error.

— Marles v. State, 919 S.W.2d 669, 670–71 (Tex. Crim. App. 1996). Thanks to David Keller.

October 31st, 2011

Judge Richard Posner Friend of lawhaha.com, Lihwei Lin, has made several choice contributions to Strange Judicial Opinions, including one posing this question: What would you do if you were a judge and had to reverse a case in which your boss had sat as the presiding judge? And what if your boss was none other than the legendary Richard Posner? Here is Lihwei’s take on the situation:

Imagine yourself in this situation: You are a newly-appointed circuit judge sitting in a circuit with the likes of Frank Easterbrook, “Rick” Posner and other judicial demigods. One day, your Chief Judge, Posner, apparently runs out of things to do in between being a chief judge, mediating the Microsoft case, and writing 5000 books, and decides to make a guest appearance by special designation in a federal trial court. In that role, he makes a few clearly reversible errors in a case, Chicago School-style no less. The case has come up for review and you are the presiding judge. What would you do?

Judge Evans confronted this dilemma of judicial review in Bankcard America, Inc. v. Universal Bancard Systems, Inc., 203 F.3d 477 (7th Cir. 2000). His footnote only three sentences into the opinion leaves you with the feeling than reversing one’s own Chief Judge is a bit more delicate than reversing your typical trial court:

It is a testament to the dedication of Chief Judge Posner that he volunteer to sit in the district court and hear this case which, at the time, needed the guiding hand of a new judge. Judge Posner, of course, carries a full load of cases on this court. He also discharges a multitude of administrative duties as the circuit’s chief judge. But that’s only part of what he does. He has written more books than many people read in a lifetime. On top of all this, in his spare time he is working as a court-appointed special mediator in the government’s blockbuster antitrust suit against Microsoft. Obviously, Judge Posner has more on his plate than a long-haul trucker working an “all you can eat” buffet line. It is a tribute to Judge Posner’s talent that he handles his many roles with such vigor, brilliance, and panache.

The only thing missing is: “I’m sooooo sorry about this, Judge. Please don’t take away my parking space.”

— Bankcard America, Inc. v. Universal Bancard Sys., Inc., 203 F.3d 477, 479 n.1 (7th Cir. 2000). Thanks to Lihwei Lin.

|

Funny Law School Stories

For all its terror and tedium, law school can be a hilarious place. Everyone has a funny law school story. What’s your story?

|

Product Warning Labels

A variety of warning labels, some good, some silly and some just really odd. If you come encounter a funny or interesting product warning label, please send it along.

|

Tortland

Tortland collects interesting tort cases, warning labels, and photos of potential torts. Raise risk awareness. Play "Spot the Tort." |

Weird Patents

Think it’s really hard to get a patent? Think again.

|

Legal Oddities

From the simply curious to the downright bizarre, a collection of amusing law-related artifacts.

|

Spot the Tort

Have fun and make the world a safer place. Send in pictures of dangerous conditions you stumble upon (figuratively only, we hope) out there in Tortland.

|

Legal Education

Collecting any and all amusing tidbits related to legal education.

|

Harmless Error

McClurg's twisted legal humor column ran for more than four years

in the American Bar Association Journal.

|

|

|