July 14th, 2012  One of Zim's classics. Remember “Golden Guides”? They were sort of the original “Dummies” series for kids, explaining a variety of scientific, geographic, and nature topics in succinct terms understandable even by 10 year olds.

Zim v. Western Pub. Co. arose out of a dispute between the guy who wrote or co-wrote many of these masterpieces—Dr. Herbert Zim—and the Golden Guides publisher, Western Publishing. Zim penned such classics as Rocks and Minerals, Reptiles and Amphibians, Trees, and my personal fav, Fishes.

Judge Goldberg of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit apparently also thinks highly of Zim, elevating him to biblical proportions:

In the beginning, Zim [Fn.1] created the concept of the Golden Guides. For the earth was dark and ignorance filled the void. And Zim said, let there be enlightenment and there was enlightenment. In the Golden Guides, Zim created the heavens (STARS) (SKY OBSERVER’S GUIDE) and the earth. (MINERALS) (ROCKS and MINERALS) (GEOLOGY).

[Fn.1] Dr. Zim is a noted science educator with a Ph.D. in science education from Columbia University. His special expertise is in the presentation of scientific subjects to popular audiences. The major focus of his efforts has been the development of a multivolume series of books on scientific subjects, the “Golden Guides.” …

And together with his publisher, Western, he brought forth in the Golden Guides knowledge of all manner of living things that spring from the earth, grass, herbs yielding seed, fruit-trees yielding fruits after their kind, (PLANT KINGDOM) (NON-FLOWERED PLANTS) (FLOWERS) (ORCHIDS) (TREES), and Zim saw that it was good. And they brought forth in the Golden Guides knowledge of all the living moving creatures that dwell in the waters, (FISHES) (MARINE MOLLUSKS) (POND LIFE), and fowl that may fly above the earth. (BIRDS) (BIRDS OF NORTH AMERICA) (GAMEBIRDS). And Zim saw that it was good. And they brought forth knowledge in the Golden Guides of the creatures that dwell on dry land, cattle, and creeping things, (INSECTS) (INSECT PESTS) (SPIDERS), and beasts of the earth after their kind. (ANIMAL KINGDOM). And Zim saw that it was very good.[Fn.4]

[Fn.4] According to Zim’s brief before this court, well over 100 million of the Golden Guide books have been printed under Zim’s name, earning him “millions of dollars” in royalties.

Then there rose up in Western a new Vice-President who knew not Zim. And there was strife and discord, anger and frustration, between them for the Golden Guides were not being published or revised in their appointed seasons. And it came to pass that Zim and Western covenanted a new covenant, calling it a Settlement Agreement. But there was no peace in the land. Verily, they came with their counselors of law into the district court for judgment and sued there upon their covenants.

And they put upon the district judge hard tasks. And the district judge listened to long testimony and received hundreds of exhibits. So Zim did cry unto the district judge that he might remember the promises of the Settlement Agreement. And the district judge heard Zim’s cry, but gave judgment for Western. Yea, the district judge gave judgment to Western on a counterclaim as well. Therefore, Zim went up out of the court of the district judge.

And Zim spake unto the Court of Appeals saying, make a sacrifice of the judgment below. And the judges, three in number, convened in orderly fashion to recount the story of the covenants and to discuss and answer the four questions which Zim brought before them …

Maybe it’s just because I loved Golden Guides, but this one goes in the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

— Zim v. Western Pub. Co., 573 F.2d 1318, 1320–21 (5th Cir. 1978). Thanks to Professor Ken Swift.

July 6th, 2012  Siskel and Kozinski? Judge Alex Kozinski, of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, was well-known for his sparkling prose in writing opinions, but his most classic opinion was U.S. v. Syufy Enterprises, in which he weaved in more than 200 movie titles.

In Syufy, the federal government sued Las Vegas movie-chain owner Syufy for antitrust violations. In affirming the trial court’s dismissal of the antitrust charges, rumor had it that Judge Kozinski wove more than 200 movie titles into the text of his fourteen-page opinion.

But did it really happen? Was it urban legend? Bourbon legend?

It really happened. Daniel Solzman of the Tarlton Library at the University of Texas law school assembled the entire list of movies Kozinski managed to cram into Syufy as part of its Law in Popular Culture Collection. Here are the movie titles in the order they appeared:

M, Suspect, Giant, Nevada, Illegal, Monkey Business, Platoon, David, 8 1/2, The Power, The Competition, Greatest Hurdle, Gone are the Days, Popcorn, Something for Everyone, Manpower, The Producers, Formula, Splash, Shame, Stir, Titanic, Easy Money, No Holds Barred, Upper Hand, Rivals, Rocky, Until September, September, Midway, The Big Picture, Do the Right Thing, Brass Knuckles, The Accused, Humongous, Little Big Man, Chances, Vice Versa, Always, Nuts, The Seven-Ups, Big, Ordinary People, Possessed, Foul Play, The Survivors, Personal Services, Time after Time, Challenge, Testimony, Riding High, Captured, Utopia, Dark Horse, Invitation, Major League, Against all Odds, Fighting Fire with Fire, Trading Places, The End, Country, Losing Ground, Short Circuit, Lock Up, Dead Heat, Personal Best, Absolute Beginners, Staying Alive, Big Business, Network, Shopworm, Witness, High Tide, The Law, Wisdom, The Hand, Guilty, Illicit, Satisfaction, The Victim, Raw Deal, The Evil, Above the Law, Down by Law, Off Limits, The Enforcer, Fear, The Villain, The Weapon, Champion, The Natural, Deliverance, The Disappearance, The Challenge, Running, The Other, Top Gun, Players, The Trial, Paid, Head, The Squeeze, Seven Days, Cold Feet, Gambit Backfire, Contract, Cold Turkey, Lost, Plenty, After Hours, The Judge, The Trap, Leviathan, Stick, Tough Enough, Making It, Risky Business, Squeeze Play, Sitting Ducks, Boomerang, Big Trouble, The Principal, House of Cards, Tribute, America, Target, Paper Tiger, Distance, Local Hero, Being There, Fire Sale, Abandoned, The Lawyer, You and Me, Avalanche, Surrender, The First Time, Hard Choices, Showdown, Fail-Safe, The Great Race, Relentless, The Fountainhead, Out, House, Volunteers, October, 1984, Over the Top, Ran, Trapped, The Gate, Hard Times, Partners, California, Barrier, Five, Colors, Exposed, Switching Channels, Checking Out, Fame, Great Expectations, Without a Trace, Perfect, Out of Bounds, Offbeat, Critic’s Choice, The Longshot, The Sure Thing, Misunderstood, Boom Town, Static, Alien, Things Change, High Hopes, The Jackpot, Drive-in, Performance, New Faces, The Thing, The Crucible, Violated, All the Right Moves, The Creator, Interiors, Clue, Fashion, Winner Take All, Any Number Can Play, Insignificance, The Harder They Fell, Missing, Shakedown, Ruthless Predator, Dangerous, Critical Condition.

Kozinski never confirmed or denied the rumors about intentionally loading up Syufy with movie titles.

— United States v. Syufy Enterprises, Inc., 903 F.2d 659 (9th Cir. 1990); see also The Syufy Rosetta Stone, 1992 BYU L. Rev. 457 (1992).

June 17th, 2012  Whatever happened to “Appellant wins”? Back in 2003, in McConnell v. Federal Election Committee, the U.S. Supreme Court cleared up a major legal dispute over campaign financing. Er, well, maybe not completely cleared up.

The basic question was whether the McCain-Feingold Act, a federal statute that imposed restrictions on political contributions, violated the First Amendment free speech rights of potential contributors. A challenging issue no doubt, but certainly not too tough for the mighty U.S. Supreme Court to resolve, right?

With nine justices voting, the result could have been as simple as 8-1, 7-2, 6-3, or 5-4 in favor of one side or the other. The nine wise ones chose a slightly more complicated path. Here is the Court’s actual voting lineup straight out of the case:

STEVENS and O.CONNOR, JJ., delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to BCRA Titles I and II, in which SOUTER, GINSBURG, and BREYER, JJ., joined. REHNQUIST, C. J., delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to BCRA Titles III and IV, in which O.CONNOR, SCALIA, KENNEDY, and SOUTER, JJ., joined, in which STEVENS, GINSBURG, and BREYER, JJ., joined except with respect to BCRA § 305, and in which THOMAS, J., joined with respect to BCRA §§ 304, 305, 307, 316, 319, and 403(b). BREYER, J., delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to BCRA Title V, in which STEVENS, O.CONNOR, SOUTER, and GINSBURG, JJ., joined. SCALIA, J., filed an opinion concurring with respect to BCRA Titles III and IV, dissenting with respect to BCRA Titles I and V, and concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part with respect to BCRA Title II. THOMAS, J., filed an opinion concurring with respect to BCRA Titles III and IV, except for BCRA §§ 311 and 318, concurring in the result with respect to BCRA § 318, concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part with respect to BCRA Title II, and dissenting with respect to BCRA Titles I, V, and § 311, in which opinion SCALIA, J., joined as to Parts I, II.A, and II.B. KENNEDY, J., filed an opinion concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part with respect to BCRA Titles I and II, in which REHNQUIST, C. J.,joined, in which SCALIA, J., joined except to the extent the opinion upholds new FECA § 323(e) and BCRA § 202, and in which THOMAS, J., joined with respect to BCRA §213. REHNQUIST, C. J., filed an opinion dissenting with respect to BCRA Titles I and V, in which SCALIA and KENNEDY, JJ., joined. STEVENS, J., filed an opinion dissenting with respect to BCRA § 305, in which GINSBURG and BREYER, JJ., joined.

Who won? I have no idea.

For embodying in a single voting lineup the reason why the most accurate answer to most legal questions is “It depends,” this case gets into the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame. If members of the world’s most powerful tribunal are unable to agree on what the law means, how could one expect poor law students to do so?

— McConnell v. Federal Election Comm’n, 540 U.S. 93 (2003). Thanks to Elise Hendricks.

June 3rd, 2012  Triple Crown threat Funny Cide caught up in weird judicial opinion. The total weirdness of Florida Court of Appeals Judge Farmer’s opinion in Funny Cide Ventures, LLC v. Miami Herald Publ’g Co. gets the case into Lawhaha.com’s Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

Here’s a first in judicial writing: an appellate judge writes an opinion in an offbeat fiction-style based on a tune from Guys and Dolls, can’t get the other judges to go along with his approach, so decides to attach his creative opinion to the court’s per curiam opinion together with a lengthy preface explaining his unique approach to written adjudication.

Confused? Let’s back up. In 2003, Funny Cide won both the Kentucky Derby and the Preakness, one race away from the Triple Crown.

After the Kentucky Derby, the Miami Herald published an article implying that the jockey cheated by using some kind of illegal battery-powered device during the race. The Herald later admitted it made an error and retracted the story. Meanwhile, Funny Cide placed third at the Belmont, missing out on becoming only the twelfth horse in history to win the Triple Crown.

In a lawsuit for injurious falsehood against the Herald, Funny Cide’s owners claimed the article caused substantial damage, including the chance to win the Belmont because “the article caused the jockey to over-ride the horse in the Preakness in an attempt to vindicate himself.”

The defendant moved for summary judgment, which was granted on the ground that the plaintiffs had not alleged direct and immediate damages from the article. The appellate court affirmed in a brief per curiam opinion.

So far, so good.

Then the reader stumbles on Judge Farmer’s … not sure what to call it … tacked on at the end of the court’s opinion. It’s not a concurring or dissenting opinion, and is not labeled as an appendix.

His “attachment” to the majority opinion is not a dissent from the reasoning of his brethren’s opinion, but the boring way in which they expressed it.

Judge Farmer starts by assailing traditional stilted judicial opinion writing, then explains why a humanized, pot-boiler narrative approach might be better. He concludes by suggesting readers compare the two approaches–his and the majority’s–and decide which is better.

Basically, he seemed to be saying: “Hey, I labored over writing this really fun and wild opinion, but these dudes I work with on the court are too straitlaced to get it, so here it is for your reading pleasure.”

Here are excerpts, first, from his attack on traditional judicial opinion writing:

Most [judicial opinions are] … dreary and tedious. …

A surprising number are way too long. There is often a painstaking account of background and trial which turns out to be unnecessary to grasp the essential issues to be decided. Many have extended discussions of rules and principles no one really challenges, or few would dispute. Judges pile on needless details of date, time and place, modified by confusing identifying terms (appellant-cross appellee-defendant) without regard to clarity. Extended comparative quotations alternate with exposition of one sort or another. Legal issues are analyzed through mind-numbing, many-factored “tests”. Each factor is unloaded nit by nit, as though the judges actually decided the dispute in precisely that way. Arcane legal terminology is woven in and out, even though simpler, plainer words could be used. Simplicity, tone, style, voice, personality, levity-all are shunned.

Judge Farmer concedes he’s been guilty of what he describes, then sets out to change his opinion-writing ways:

From the very moment of my appointment as a judge, I have chafed under this norm for appellate opinion writing. How did it become conventional? Who made it required? Why hasn’t it been changed?

I struggled against it. There must be other styles, different tones, alternate voices. Not for every opinion. But for some.

One technique occurred to me. This idea would have an opinion in some of the forms, styles and characteristics associated with fiction. Good fiction is set in human experience. Good fiction illuminates.

***

I had decided that the style of some opinions could-and should-be unconventionally changed for greater openness to all readers. I would try to write some opinions in styles and tones calculated to make legal reasoning clearer for those without law degrees. Then came this case.

When the panel conferred after oral argument, I did not detect any disagreement. … So after thinking on the matter, I conceived of an unconventional approach. I would try a style, a tone, a voice to make apparent even to non-lawyers what I believed is the basic defect in their argument. The very style of the opinion itself would illuminate the legal analysis and outcome.

As it turns out, the other two members of the panel could not endorse the opinion or even some slightly altered version. They had concerns. Some other judges shared them. So I give this explanation for what I wrote, laying my version along side the panel’s substitute. Readers can compare a conventional opinion with an unconventional style-the pious with the impious.

Then comes the opinion. Here’s an excerpt, inspired by the opening song of Guys and Dolls, Fugue for the Tinhorns:

Then the horse won the Preakness Stakes. And it’s not even close. Wins by nearly ten lengths. The horse is so far out front, looks like he could make it past the wire and into the barn before they can take the photo. Hardly anyone asked if the horse ran out of gas for the Belmont. Are you kidding? Racing was all stirred up about the Crown. The feedbox noise grew hot.

Was it a dream, or did I hear stories about a guy who read in the paper the horse wins it all by a half? About another guy who said it was no bum steer, it was from a handicapper that’s real sincere? Even about a third guy who knew this is the horse’s time because his father’s jockey’s brother’s a friend?

Whatever. It’s a lock. Two jewels for the Crown. Make room for the third.

Only, wait a minute. Did I hear another story about this one guy who wasn’t so sure? Said it all depends if it rained last night?

For the life of me, I can’t understand why the other judges on the panel were hesitant to join in this opinion.

— Funny Cide Ventures, LLC v. Miami Herald Publ’g Co., 955 So.2d 1241, 1243–47 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2007). Thanks to Kevin McDowell and James Heelan.

May 27th, 2012  Bird expert "thinks" this might be a bird. In U.S. v. Byrnes, the defendant was convicted of making false statements to a grand jury investigating illegal trafficking in exotic birds. The issue involved the materiality of statements as to whether some illegally imported swans and geese were dead or live when the defendant received them.

To bolster its case, the government called a collector of Australian parrots who testified the defendant had delivered some swans and geese to her. Defense counsel cross-examined the witness, an immigrant from Germany who had difficulty speaking English, in an apparent effort to challenge her credibility as a bird expert. Here’s the interesting colloquy:

Q. Mrs. Meffert, do you recall testifying yesterday about your definition of birds?

A. Yes.

Q. And do you recall that you said that the swans and geese were not birds?

A. Not to me.

Q. What do you mean by that, “not to me?”

A. By me, the swans are waterfowls.

Shortly thereafter, Mrs. Meffert was cross examined as follows:

Q. Are sparrows birds?

A. I think so, sure.

Q. Is a crow a bird?

A. I think so.

Q. Is a parrot a bird?

A. Not to me.

Q. How about a seagull, is that a bird?

A. To me it is a seagull, I don’t know what it is to other people.

Q. Is it a bird to you as well or not?

A. To me it is a seagull. I don’t know any other definition for it.

Q. Is an eagle a bird?

A. I guess so.

Q. Is a swallow a bird?

A. I don’t know what a swallow is, sir.

Q. Is a duck a bird?

A. Not to me, it is a duck.

Q. But not a bird.

A. No, to other people maybe.

The government stipulated that swans and geese are birds.

Because it makes me laugh every time I read it, this opinion gains entry to the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

— United States v. Byrnes, 644 F.2d 107, 110 n.7 (2nd Cir. 1981). Thanks to Walter Fitzpatrick.

April 7th, 2012

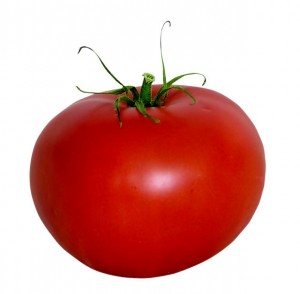

It's official. Tomatos are vegetables according to the Supreme Court. The next time someone raises the age-old debate as to whether a tomato is a fruit or a vegetable, show off your legal acuity (or nerdiness) by informing them you have it on good authority that tomatos are vegetables. No, in fact, make that great authority. Who? The U.S. Supreme Court.

More than 100 years ago, in Nix v. Hedden, Justice Horace Gray, speaking on behalf of a unanimous Supreme Court, ruled that a tomato is a vegetable as a matter of law.

The Tariff Act of 1883 declared a 10 percent duty on all vegetables entering the country, but allowed fruit to enter duty-free. The New York Customs Collector saw an opportunity to increase revenue and declared the tomato to be a vegetable.

Angry importers sued and their case reached the Supreme Court, where Justice Gray said: “[A]lthough botanists consider the tomato a fruit, tomatoes are eaten as a principal part of a meal, like squash or peas, (and all grow on vines), so it is the court’s decision that the tomato is a vegetable.”

— Nix v. Hedden, 149 U.S. 304 (1893). Thanks to Lihwei Lin.

April 4th, 2012  “Excuse me, I’d like to have a few words with you about the litter box issue.” Miles v. City Council of Augusta, GA—starring “Blackie the Talking Cat”—is our kind of case: completely WEIRD, so weird that it qualifies for Lawhaha.com’s Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

The plaintiffs, Carl and Elaine Mills, were an unemployed, married couple who owned Blackie, a cat who could allegedly speak English. The plaintiffs were entrepreneurs in the true American mold, making their entire living marketing Blackie’s unique vocal abilities to the public. Although the closest Blackie ever came to making the big time was a $500 appearance on “That’s Incredible” in 1980, he generated steady income for Carl and Elaine by talking to strangers on the street in return for contributions.

After receiving complaints, the Augusta Police Department warned Carl and Elaine that they needed to obtain a business license to continue peddling Blackie’s talents on the streets of Augusta. Plaintiffs sued the city, alleging the occupational license tax was unconstitutional.

The whole opinion is interesting, but the craziest part was the trial judge’s disclosure in a footnote of an ex parte street encounter with Blackie (some paragraph breaks inserted):

In ruling on the motions for summary judgment, the Court has considered only the evidence in the file. However, it should be disclosed that I have seen and heard a demonstration of Blackie’s abilities.

The point in time of the Court’s view was late summer, 1982, well after the events contended in this lawsuit. One afternoon when crossing Greene Street in an automobile, I spotted in the median a man accompanied by a cat and a woman. The black cat was draped over his shoulder. Knowing the matter to be in litigation, and suspecting the cat was Blackie, I thought twice before stopping. Observing, however, that counsel for neither side was present and that any citizen on the street could have happened by chance upon this scene, I spoke, and the man with the cat eagerly responded to my greeting.

I asked him if his cat could talk. He said he could, and if I would pull over on the side street he would show me. I did, and he did. The cat was wearing a collar, two harnesses and a leash. Held and stroked by the man Blackie said “I love you” and “I want my Mama.”

The man then explained that the cat was the sole source of income for him and his wife and requested a donation which was provided. I felt that my dollar was well spent …

I never understood why a cat that could talk didn’t become more famous.

— Miles v. City Council of Augusta, Ga., 551 F. Supp. 349, 350 n.1 (S.D. Ga. 1982). Thanks to Richard McKewen.

April 1st, 2012 A pro se litigant in Arkansas appealed a trial court decision granting custody of her child to the biological father and ordering that the child’s birth name be changed. The trial court granted the custody change and ordered the child’s name be changed to “Samuel Charles.” Not a bad name, but why order a change? Personally, I liked the original name: “Weather’By Dot Com Chanel Fourcast.”

For making us laugh out loud, this order gets into the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

Here’s the colloquy in which the perplexed trial judge asked the mother to explain the child’s birth name:

The Court: I simply do not understand why you named this child — his legal name is Weather’By Dot Com Chanel Fourcast Sheppard. Now, before you answer that, Mr. – the plaintiff in this action is a weatherman for a local television station?

Sheppard: Yes.

The Court: Okay. Is that why you named this child the name that you gave the child?

Sheppard: It – it stems from a lot of things.

The Court: Okay. Tell me what they are.

Sheppard: Weather’by — I’ve always heard of Weatherby as a last name and never a first name, so I thought Weatherby would be — and I’m sure you could spell it b-e-e or b-e-a or b-y. Anyway, Weatherby.

The Court: Where did you get the “Dot Com”?

Sheppard: Well, when I worked at NBC, I worked on a Teleprompter computer.

The Court: All right.

Sheppard: All right, and so that’s where the Dot Com [came from]. I just thought it was kind of cute, Dot Com, and then instead of — I really didn’t have a whole lot of names because I had nothing to work with. I don’t know family names. I don’t know any names of the Speir family, and I really had nothing to work with, and I thought “Chanel”? …

The Court: Well, where did you get “Fourcast”?

Sheppard: Fourcast? Instead of F-o-r-e, like your future forecast or your weather forecast, F-o-u, as in my fourth son, my fourth child, Fourcast. It was —

The Court: So his name is Fourcast, F-o-u-r-c-a-s-t?

Sheppard: Yes.

The Court: All right. Now, do you have some objection to him being renamed Samuel Charles?

Sheppard: Yes.

The Court: Why? You think it’s better for his name to be Weather’by Dot Com Chanel —

Sheppard: Well, the —

The Court: Just a minute for the record.

Sheppard: Sorry.

The Court: Chanel Fourcast, spelled F-o-u-r-c-a-s-t? And in response to that question, I want you to think about what he’s going to be — what his life is going to be like when he enters the first grade and has to fill out all [the] paperwork where you fill out — this little kid fills out his last name and his first name and his middle name, okay? So I just want – if your answer to that is yes, you think his name is better today than it would be with Samuel Charles, as his father would like to name him and why. Go ahead.

Sheppard: Yes, I think it’s better this way.

The Court: The way he is now?

Sheppard: Yes. He doesn’t have to use “Dot Com.” I mean, as a grown man, he can use whatever he wants.

The Court: As a grown man, what is his middle name? Dot Com Chanel Fourcast?

Sheppard: He can use Chanel, he can use the letter “C.”

The Court: And when he gives his Birth Certificate — is it on his birth certificate as you’ve stated to the Court? Does his Birth — does this child’s Birth Certificate read “Weather’by Dot com” —

Sheppard: That’s how I filled out the paperwork for his —

The Court: — Chanel Fourcast?

Sheppard: Yes, and for his Social Security card, I filled it out as Weather’by F. Sheppard.

The Court: All right.

The Arkansas court of appeals upheld the trial judge’s ruling based largely on its finding that the birth name could subject the child to embarrassment.

— Sheppard v. Speir, 157 S.W.3d 583, 587–88 (Ark. Ct. App. 2004). Thanks to David Eanes.

December 4th, 2011  Judge Carlin LOVED this guy. A unanimous Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame opinion is Cordas v. Peerless Transportation Co., penned in 1941 by Judge Carlin (no relation to George) of the New York City Court.

The defendant was a chauffeur and the victim of an armed car-jacking by a fleeing robber who threatened to blow the chauffeur’s brains out. In fright, the chauffeur slammed on the brakes and jumped out of the vehicle, which kept moving and hit the plaintiff pedestrian and her children (fortunately, injuries were slight).

The case stands for the unremarkable principle that under the basic negligence standard of reasonable care “under the circumstances,” people aren’t expected to exercise as much care in emergency situations as in non-emergencies where they have time to weigh and deliberate. It also stands as a literary masterpiece of judicial opinion writing.

Full appreciation of this classic can come only with a full reading, but here’s how it starts:

This case presents the ordinary man–that problem child of the law–in a most bizarre setting. As a lowly chauffeur in defendant’s employ he became in a trice the protagonist in a breath-bating drama with a denouement almost tragic. It appears that a man, whose identity it would be indelicate to divulge, was feloniously relieved of his portable goods by two nondescript highwaymen in an alley near 26th Street and Third Avenue, Manhattan; they induced him to relinquish his possessions by a strong argument ad hominem couched in the convincing cant of the criminal and pressed at the point of a most persuasive pistol.

Carlin apparently was a learned Shakespeare fan. In excusing the chauffeur from liability for jumping out of the moving vehicle, Carlin said:

If the philosophic Horatio and the martial companions of his watch were ‘distilled almost to jelly with the act of fear’ when they beheld ‘in the dead vast and middle of night’ the disembodied spirit of Hamlet’s father stalk majestically by ‘with a countenance more in sorrow than in anger,’ was not the chauffeur, though unacquainted with the example of these eminent men-at-arms more amply justified in his fearsome reactions when he was more palpably confronted by a thing of flesh and blood bearing in its hand an engine of destruction which depended for its lethal purpose upon the quiver of a hair.

Translation: It’s not negligent to react in fright when a carjacker has a gun pointed at your head.

— Cordas v. Peerless Transp. Co., 27 N.Y.S.2d 198, 199, 201 (City Court of N.Y. 1941). Thanks to all the folks who sent in this classic.

November 27th, 2011  U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts let loose his inner-Raymond Chandler. It’s not often that members of the world’s most powerful judicial tribunal have fun with their opinion-writing, but now, following in the great tradition of hard-boiled crime writers like Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, and Ross MacDonald comes … U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Roberts? Yup.

In Pennsylvania v. Dunlap, a mundane drug case, Justice Roberts, dissenting from a denial of cert review, explored his inner Joe Friday. Here’s how his dissent started out:

North Philly, May 4, 2001. Officer Sean Devlin, Narcotics Strike Force, was working the morning shift. Undercover surveillance. The neighborhood? Tough as a three dollar steak. Devlin knew. Five years on the beat, nine months with the Strike Force. He’d made fifteen, twenty drug busts in the neighborhood.

Devlin spotted him: a lone man on the corner. Another approached. Quick exchange of words. Cash handed over; small objects handed back. Each man then quickly on his own way. Devlin knew the guy wasn’t buying bus tokens. He radioed a description and Officer Stein picked up the buyer. Sure enough: three bags of crack in the guy’s pocket. Head downtown and book him. Just another day at the office.

Roberts proceeded, in a much more traditional fashion, to disagree with the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s decision that the officer lacked probable cause to arrest the defendant.

Because it’s the only case we know of where a U.S. Supreme Court justice, a conservative one at that, had fun in an opinion, this opinion joins the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

— Pennsylvania v. Dunlap, 129 S. Ct. 448, 448 (2008). Thanks to Joel Dipippa.

November 24th, 2011 Why waste words? Wouldn’t it be nice if more judges could cut to the chase like Judge J.H. Gillis of the Michigan Court of Appeals? Here’s his entire opinion in Denny v. Radar Indus., Inc.:

J.H. Gillis, Judge.

The appellant has attempted to distinguish the factual situation in this case from that in Renfroe v. Higgins Rack Coating and Manufacturing Co., Inc. (1969), 17 Mich. App. 259, 169 N.W.2d 326. He didn’t. We couldn’t.

Affirmed. Costs to appellee.

As the most succinct judicial opinion known to Lawhaha.com, Judge Gillis’ effort enters the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

— Denny v. Radar Indus., Inc., 184 N.W.2d 289 (Mich. App. 1970). Thanks to Richard McKewen.

November 17th, 2011 You don’t have to be a famous judge or blessed with a crazy case to write a Hall of Fame Strange Judicial Opinion. Here we have a low-level New Zealand trial judge trying to educate his appellate court masters about life down in the “real world” trial court-trenches, and a good-humored, self-effacing reply from the appellate court.

In New Zealand, an appeal over a $100 fine for failure to register “a handsome German Shepherd named Ben” apparently irritated the overworked trial judge. In a memorandum, the judge sought to educate the high court about the process for administering justice in his humble court at the bottom of the judicial hierarchy:

Your honour may not be familiar with the manner in which “Minor Offences” are dealt with in this Court. Notices of Prosecution . . . are surreptitiously placed in the Judge’s “In Tray” at frequent and irritating intervals, usually in his or her absence. They come in stacks and bundles … [The trial judge proceeds to describe the variety of matters crying out for his daily attention, including applications for Massage Parlor licenses, truancy notices, underage drinking citations, etc.]

The Judge peruses the mountain of files with great care and then imposes whatever he or she deems appropriate. No hearing is held. No defendant or counsel are present. No submissions are made. No tears are shed. No howls of derision are heard from the gallery. … No anxious mother suckles a fretful child. There are no sideways glances or rolling back of eyes from counsel’s table and certainly no titters are heard to run around the Court.

The Judge sits alone in his chambers and affixes his facsimile signature to the Information Sheet perhaps muttering silent curses to himself as he does so. …

I hope this short memorandum may assist Your Honour in dealing with this appeal.

High Court Justice Grant Hammond (pretty sure this is him–please correct if wrong), chragined, contrasted the trial judge’s mundane existence with the grandeur of his much more regal appellate court, describing how on the day of the hearing over the hundred-dollar appeal, “[i]n full High Court regalia we processed bewigged and black-robed through several levels” of the court building.

It was clear Justice Hammond felt awkward about “tinkering” with the trial judge’s work. He quoted political philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s description of court systems as “a fathomless and boundless chaos, made up of fiction, tautology, technicality and inconsistency, and the administration of it a system of exquisitely contrived chicanery which maximises delay and the denial of justice.”

In the end, Hammond’s court reduced the fine to $20 because the appellant didn’t have the money to pay the higher fine.

— Lowe v. Auckland City Council (High Court, Auckland, AP44/93, 12 May 1993, Hammond, J.). Thanks to Lina Lim.

November 16th, 2011  A washing machine laughing hysterically at Judge Brown's opinion. In 1973, the Fifth Circuit struck down a Dade County detergent labeling ordinance, finding that the ordinance, intended to reduce pollution from ingredients found in household detergents, was preempted by the Federal Hazardous Substance Labeling Act.

Chief Judge John Brown concurred, managing to work in the brand names of just about every detergent product available, becoming a humorous opinion-writing path-breaker.

Let us know if we’re wrong, but Judge Brown’s opinion–published in 1973–may be the first overtly intentional effort by a federal court of appeals judge to write a clever and funny opinion. It’s a lot easier for a state judge to get away with being amusing than a federal judge, certainly a court of appeals judge.

So, while the opinion isn’t particularly hilarious, Judge Brown’s boldness and innovation gets this case into the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

Here’s a taste of his detergent-filled ruling (italics inserted):

As Proctor of this dispute … the Court holds that Congress has specifically preempted regulatory action by Dade County. Clearly, the decision represents a Gamble since we risk a Cascade of criticism from an increasing Tide of ecology-minded citizens. Yet, a contrary decision would most likely have precipitated a Niagara of complaints from an industry which justifiably seeks uniformity in the laws with which it must comply. Inspired by the legendary valor of Ajax, who withstood Hector’s lance, we have Boldly chosen the course of uniformity in reversing the lower Court’s decision upholding Dade County’s local labeling laws. And, having done so, we are Cheered by the thought that striking down the regulation by the local jurisdiction does not create a void which is detrimental to consumers ….

…

And so we hold. This is all that need be said. It is as plain as Mr. Clean the proper Action is that the Dade County Ordinance must be superseded, as All comes out in the wash.

— Chem. Specialties Mfrs. Ass’n v. Clark, 482 F.2d 325, 328–29 (5th Cir. 1973) (Brown, C.J., concurring). Thanks to Craig A. Wilson.

November 15th, 2011 Most “funny” judicial opinions aren’t ha-ha funny. They’re merely amusing or interesting. But Lawhaha.com’s scientific focus group tests showed that the colloquy below between the chastised lawyer and the judge makes people laugh out loud. For that, it’s in the SJO Hall of Fame.

In Ahmed v. Reiss Steamship Co., a federal judge held the plaintiff’s lawyer in contempt of court for failure to appear for trial. Judge Ann Aldrich (N.D. Ohio) was disturbed that the lawyer had “told two different federal district court judges that he was appearing before the other,” sort of the legal version of the old childhood stratagem for a night out in which each kid tells his parents he’s spending the night at the other’s house.

Things turned bizarre when the lawyer finally decided to explain his absence, in a way the court found to be “lacking taste and any respect for courtroom decorum”:

MR. JAQUES: I wasn’t here because I couldn’t be here. I was not here, Judge, because I had the screaming itches in the crotch. I was so badly in need of medical care that I had been in communication with my physician a lot. Judge, I wasn’t here because I would have been scratching my testicles constantly if I had been here. Judge–

THE COURT: Mr. Jaques–

MR. JAQUES: Judge, do you understand that?

THE COURT: You don’t have to be so graphic. You could have simply let the Court know that for medical reasons you were not going to be here and you could have–

MR. JAQUES: Judge, it was not a medical reason that I would have been able to frame earlier. That’s one thing.

THE COURT: It doesn’t seem awfully difficult to me. Is there anything else?

The lawyer submitted a letter from his doctor to bolster his claim:

It has been recommendation (sic) … that because of the nature, location and symptoms of this ailment he should avoid to be in public places and mainly court appearances all of which could jeopardize his professional appearance …

While the judge did not “question the intensity of [the lawyer’s] discomfort,” she held him in contempt for not notifying the court of the problem and for representing that he couldn’t attend trial because he was appearing before another judge.

— Ahmed v. Reiss S.S. Co., 580 F. Supp. 737, 742 (N.D. Ohio 1984). Thanks to Michael Slodov.

November 14th, 2011 As a member of a Memphis rock cover band that plays several Beatles songs and a huge Beatles fan, I have a special appreciation for Montana Judge Gregory R. Todd’s order in a 2007 criminal case.

After the defendant pleaded guilty to burglary, he was asked to fill out portions of a pre-sentence investigation report. In response to the question, “Give your recommendation as to what you think the Court should do in this case,” the defendant replied, “Like the Beetles say, ‘Let It Be.’”

Judge Todd took issue with both the defendant’s apparent plea for leniency and also his misspelling of the name of the Beatles, for whom Judge Todd obviously has great fondness. The judge penned a caustic sentencing memorandum, written to the defendant, that managed to work in the titles of thirty-nine Beatles songs:

Act Naturally

Baby It’s You

Bad Boy

Carry That Weight

Come Together

Day in the Life

Do You Want to Know a Secret?

Fixing a Hole

Fool on the Hill

Get Back

Hard Day’s Night

Hello Goodbye

Help

Here, There and Everywhere

Hey Jude

Honey Don’t

I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party

I Feel Fine

I Should Have Known Better

I, Me, Mine

I’ll Cry Instead

I’ll Get You

I’m a Loser

Let It Be

Long and Winding Road

Magical Mystery Tour

Misery

Mr. Moonlight

Nowhere Man

Run for Your Life

Something

Strawberry Fields Forever

The Word

Think for Yourself

Ticket to Ride

Wait

We Can Work It Out

When I’m 64

You Really Got a Hold on Me

Here’s a taste from the last paragraph of the memorandum:

Later when you thought about what you did, you may have said I’ll Cry Instead. Now you’re saying Let It Be instead of I’m A Loser. As a result of your Hard Day’s Night, you are looking at a Ticket To Ride that Long and Winding Road to Deer Lodge. Hopefully you can say both now and When I’m 64 that I Should Have Known Better.

Judge, what can I say, but Thank You Girl, er rather, Your Honor. Til There Was You, most judicial opinions were just so Yesterday. I hope we have a chance to Come Together for lunch or Something. Why? Well, just Because.

— State v. McCormack, No. DC06-0323, Montana Thirteenth Judicial District, Yellowstone County, Feb. 26, 2007. Thanks to Pat Smith.

November 14th, 2011 In a classic slip and fall case, plaintiff Joseph Rosenberg slipped on asparagus while dancing at a wedding reception with his sister-in-law and fellow plaintiff, Ruth Schwartz.

The issue was whether the defendant caterer had negligently spilled the asparagus on the dance floor. The trial judge had dismissed the lawsuit on theory that the offending asparagus could have been unwittingly transported onto the dance floor after becoming entrapped in the apparel of the dancers.

As with many of the judicial opinions posted on Lawhaha.com, brief excerpts don’t do this case justice. My favorite part is how the legendary Justice Michael Angelo Musmanno of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court bluntly and rather contemptuously rejected the trial judge’s theory of how the asparagus (which according to testimony formed a puddle three feet in diameter) got on the dance floor (some paragraph breaks inserted):

The trial judge, an ex-veteran congressman and thus a habitue of formal parties and accordingly an expert in proper wearing apparel at such functions, all of which he announced from the bench, allowed testimony as to the raiment worn by the banquetters.

All the men were attired in tuxedos, the pants of which were not mounted with cuffs which could transport asparagus and sauce to the dance floor, unwittingly to lubricate its polished surface. Ruling out the cuffs of the tuxedo pants as transporters of the asparagus, the judge suggested the asparagus, with its accompanying sauce, could have been conveyed to the dance floor by ‘women’s apparel, on men’s coats or sleeves, or by a guest as he table hopped.’

The Judge’s conclusions are as far-fetched as going to Holland for hollandaise sauce. There was no evidence in the case that anybody table hopped; it is absurd to assume that a man’s coat or sleeve could scoop up enough asparagus and sauce to inundate a dance floor to the extent of a three-foot circumference; and it is bizarre to conjecture that a woman’s dress without pockets and without excessive material could latch on to such a quantity of asparagus, carry it 20 feet (the distance from the tables to the dance floor) and still have enough dangling to her habiliments to cover the floor to such a depth as to fell a 185 pound gentleman with 35 years’ dancing experience who had never before been tackled or grounded while shuffling the light fantastic.

…

It can be stated as an incontrovertible legal proposition that anyone attending a dinner dance has the inalienable right to expect that, if asparagus is to be served, it will be served on the dinner table and not on the dance floor.

…

Judgment reversed with a procedendo.

Chief Justice Bell dissented:

One cannot help wondering if plaintiffs had, in the alleged 35 years of dancing, ever been to any dance, let alone a wedding banquet dance. … A dancer cannot, with legal sanction, look only into the captivating eyes of his lovely partner.

I certainly dissent.

— Schwartz v. Warwick-Philadelphia Corp., 226 A.2d 484, 485–87, 488 (Pa. 1967). Thanks to Janet Heydt.

November 14th, 2011 The classic dilemma of the law. Which is more important: following the rules or dispensing justice? Being faithful to precedent or willing to bend technical legal rules to reach the correct result?

We struggle with these issues from the time we’re first-year law students. Rules won out in ugly fashion in In re Estate of Pavlinko.

Vasil Pavlinko and his wife, Hellen, immigrants who spoke little English, went to a lawyer to have separate wills drawn up. Both wills left their residual interest to the same person: Elias Martin, the brother of Hellen Pavlinko. Unfortunately, when it came time to sign the wills, the wills got mixed up and Vasil and Hellen each signed the other’s will.

After the couple died, Elias Martin—the sole residuary legatee under both wills—offered Vasil’s will for probate. Although conceding that the result was “unfortunate,” the Pennsylvania Supreme Court rejected Martin’s petition because Vasil had mistakenly signed Hellen’s will.

Judge Michael Angelo Musmanno, a Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Famer for his intelligent prose, dissented, in an impassioned Ode to Screwing Up:

Everyone in this case admits that a mistake was made: an honest, innocent, unambiguous, simple mistake, the innocent, drowsy mistake of a man who sleeps all day and, on awakening, accepts the sunset for the dawn.

Nothing is more common to mankind than mistakes. Volumes, even libraries have been written on mistakes: Mistakes of law and mistakes of fact. In every phase of life, mistakes occur and there are but few people who will not attempt to lend a helping hand to the person who mistakes a step for a landing and falls, or the one who mistakes a nut for a grape and chokes, or the one who steps through a glass so clear that he does not see it. This Court, however, says that it can do nothing for the victim of the mistake in this case, a mistake which was caused through no fault of his own, nor of his intended benefactors.

… I know that the law is founded on precedent and in many ways we are bound by the dead hand of the past. But even with obeisance to precedent, I still do not believe that the medicine of the law is incapable of curing the simple ailment here ….

We have said more times than there are tombstones in the cemetery where the Pavlinkos lie buried, that the primary rule to be followed in the interpretation of a will is to ascertain the intention of the testator. Can anyone go to the graves of the Pavlinkos and say that we do not know what they meant? They said in English and Carpathian that they wanted their property to go to Elias Martin.

— In re Estate of Pavlinko, 148 A. 2d 528, 532 (Pa. 1959) (Musmanno, J., dissenting). Thanks to Frank Zotter.

November 6th, 2011 Of all the judicial opinions that have been reviewed at lawhaha.com, People v. Arno takes the cake for the most over-the-top, unjudicial attack on a colleague in a written opinion. For that reason, it qualifies for the Strange Judicial Opinions Hall of Fame.

Arno was a Fourth Amendment obscenity case in which the Second District California Court of Appeals suppressed evidence obtained by the police from peering in the windows of defendant’s office suite with ten-power binoculars.

One judge—we’ll leave names out to protect all the guilty judges involved—filed a strong dissent. Actually, it was more than strong. It was strident and no doubt irritating to the judge’s colleagues on the appellate panel.

But the attack launched by the majority judges against their dissenting brethren in footnote 2 is almost breathtaking in its inappropriateness. You don’t bother to read the whole footnote. Just read the first letters of the seven numbered sentences. As Country Joe McDonald shouted at Woodstock: “What’s that spell? What’s that spell?”

2. We feel compelled by the nature of the attack in the dissenting opinion to spell out a response:

1. Some answer is required to the dissent’s charge.

2. Certainly we do not endorse “victimless crime.”

3. How that question is involved escapes us.

4. Moreover, the constitutional issue is significant.

5. Ultimately it must be addressed in light of precedent.

6. Certainly the course of precedent is clear.

7. Know that, our result is compelled.

How did the dissenter reply to this profane insult? Well, not surprisingly, with even more bizarre stridency. In his own footnote, he said:

I have heretofore eschewed responding to footnote 2 of the majority opinion in kind since it would be beneath the dignity of this office. Although I still will not respond in kind, … some comment is compelled.

I decry the lack of propriety, collegiality and judicial temperament displayed in footnote 2. I abhor the loss of public respect for the legal profession and the judiciary footnote 2 engendered by reason of [a L.A. Times story about the footnote]. …

I construe the [footnote reference] as a personal affront to every California citizen and their duly elected representatives … who have deemed it a wise public policy to enact our criminal obscenity laws …. It is no wonder that California had the odious distinction of being the porno capital of the world.

Come on, judges. Play nice or we’ll take your robes away.

— People v. Arno, 153 Cal. Rptr. 624, 628 n.2 (majority), 644 n.14 (dissent) (Cal. Ct. App. 1979).

|

Funny Law School Stories

For all its terror and tedium, law school can be a hilarious place. Everyone has a funny law school story. What’s your story?

|

Product Warning Labels

A variety of warning labels, some good, some silly and some just really odd. If you come encounter a funny or interesting product warning label, please send it along.

|

Tortland

Tortland collects interesting tort cases, warning labels, and photos of potential torts. Raise risk awareness. Play "Spot the Tort." |

Weird Patents

Think it’s really hard to get a patent? Think again.

|

Legal Oddities

From the simply curious to the downright bizarre, a collection of amusing law-related artifacts.

|

Spot the Tort

Have fun and make the world a safer place. Send in pictures of dangerous conditions you stumble upon (figuratively only, we hope) out there in Tortland.

|

Legal Education

Collecting any and all amusing tidbits related to legal education.

|

Harmless Error

McClurg's twisted legal humor column ran for more than four years

in the American Bar Association Journal.

|

|

|